The Supreme Court has upheld the constitutional validity of the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, dismissing the Allahabad High Court verdict that struck down the legislation earlier this year. A three-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud ruled that the High Court “erred” in quashing the Madarsa Act on the ground that it violated the basic constitutional tenet of secularism.

The order comes as a huge relief to thousands of students and teachers in Uttar Pradesh madarsas as the Allahabad HC had directed the closure of these institutions and integration of students into the mainstream education system.

Let’s take a closer look.

What is the UP Madarsa Act 2004?

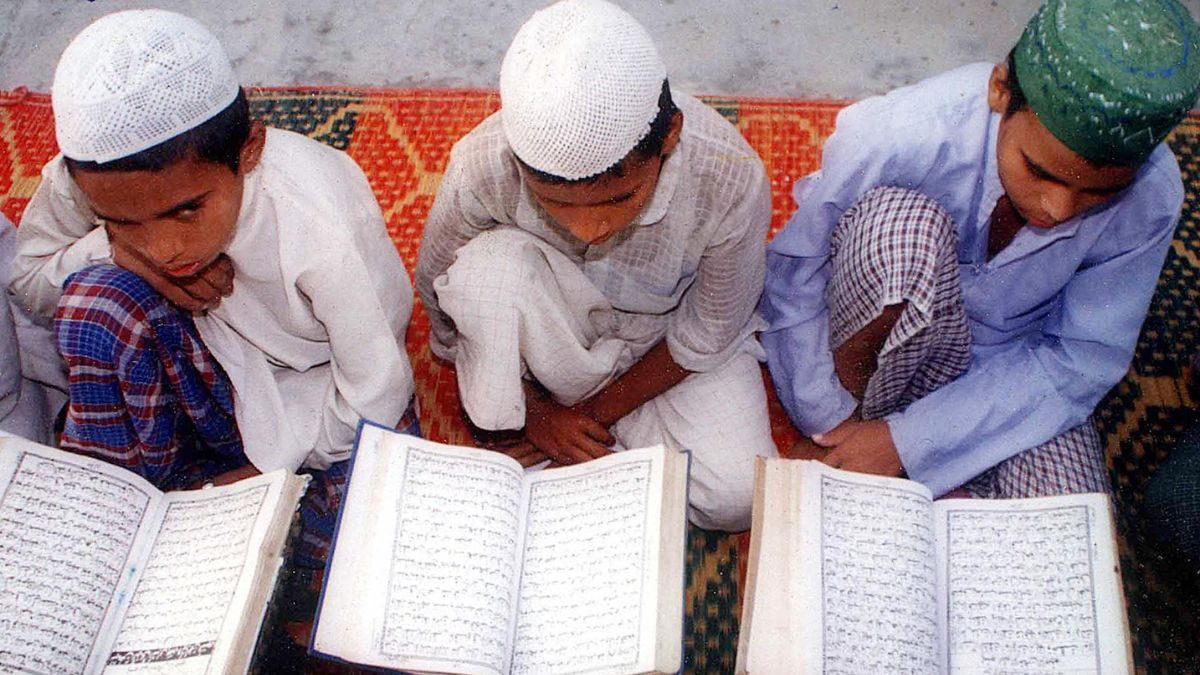

The Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, was introduced to streamline education in madarsas , providing a legal framework. Madarsa education has been defined as education in Arabic, Urdu, Persian, Islamic studies, Tibb (traditional medicine), philosophy and other branches, as per Times of India (TOI).

In these Islamic schools, pupils study the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) syllabus, along with religious education.

The Act led to the creation of the UP Board of Madarsa Education, which mainly consists of Muslim members. This board prepares course material, conducts exams and awards degrees, including undergraduate and postgraduate degrees known as Kamil and Fazil respectively.

There are 16,513 recognised and 8,449 unrecognised madrasas in UP, with roughly 25 lakh students, as per Indian Express.

Why Allahabad HC quashed UP Madarsa Act 2004

A petition was filed by the lawyer Anshuman Singh Rathore challenging the Madarsa Act, saying “the provisions, scheme and the environment” violate Articles 14 (right to equality before law), 15 (prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth) and 21-A (right to free and compulsory education for children between the ages of six and 14) of the Constitution.

“The fundamental rights under the aforesaid articles, more specifically under Article 14 and 21-A, include the right to universal quality education, which also includes secular education,” he claimed.

In March, the Allahabad High Court struck down the UP Madarsa Act, calling it “unconstitutional”.

A bench of Justices Subhash Vidyarthi and Vivek Chaudhary ruled on March 22 that the Act violated the principle of secularism. The HC said that “… (it is) compulsory for a student of Madarsa to study in every class, Islam as a religion, including all its prescriptions, instructions and philosophies… The modern subjects are either absent or are optional…”

Impact Shorts

More ShortsThe court said it was the government’s duty to impart secular education and not “discriminate” by providing education based on religion.

The bench also observed that the state was denying “quality” education to madarsa students in modern subjects.

Moreover, the court held that the Act was “violative of Section 22 of the University Grants Commission Act, 1956”. It said that as per the UGC Act, only universities or institutions “deemed to be a University” can grant degrees, and “no other person or authority, including any Madarsa or the Madarsa Board, can confer any degree”.

The HC ordered the state government to “take steps forthwith for accommodating the madrasa students in regular schools recognised under the Primary Education Board and schools recognised under the High School and Intermediate Education Board of the state of Uttar Pradesh”.

On April 5, the top court stayed the High Court’s decision until it decided on the validity of the law.

What has the SC said?

Upholding the constitutional validity of the UP Madarsa Act, the Supreme Court on Tuesday (November 5) set aside the Allahabad High Court’s March ruling.

However, the apex court deemed the provisions of the legislation regulating higher education degrees such as Fazil and Kamil unconstitutional, finding them in conflict with the UGC Act.

“The Madrasa Act regulates the standard of education in Madarsa as recognised by the Board for imparting Madarsa education….is consistent with the positive obligation of the state to ensure that students studying and recognised Madrasas attain a level of competency which will allow them to effectively participate in society and earn a living,” CJI Chandrachud said while reading out the judgement, as per Indian Express.

The top court noted that “the provisions of the Act are reasonable because they subserve the objective recognition that is improving the academic excellence of students in the recognised Madrasas and making them capable to sit for examinations conducted by the board.”

The bench, also comprising Justices JB Pardiwala and Manoj Misra, said the Madarsa Act “secures” the interests of the minority community in UP as it regulates the standard of education in these institutes, organises exams and confers certificates to students that allow them to pursue higher education.

The judgement said that the Allahabad HC “erred in holding that the education provided under the Madrasa Act is violative of Article 21A because the Right to Education Act, which facilitates the fulfillment of the fundamental right under Article 21A, contain the specific provision by which it does not apply to minority educational institutions”.

The top court added that “the right of religious minority to establish and administer to impart both religious and secular education is protected by Article 30” and “the Board and the state government have sufficient regulatory powers to prescribe and regulate standards of education for the Madrasas.”

The bench said that while Madrasas impart “religious instruction, their primary aim is education.”

The apex court held that the corollary to Article 28(3) is “that religious instruction may be imparted in an educational institution, which is recognised by the state or which receives state aid, but no student can be compelled to participate in religious instruction in such an institution.”

As per Indian Express, during the hearings of the case in October, two questions had emerged before the apex court: whether madarsas impart “religious education” or “religious instruction” and whether it was correct for the HC to strike down the entire Act instead of restricting its order to certain provisions.

The UP government had told the Supreme Court it believed that the law was constitutional and should not have been quashed entirely, but some provisions needed to be scrutinised.

The top court had on October 22 reserved its judgement on pleas challenging the Allahabad High Court order.

The CJI noted earlier that the verdict in this case could have wider ramifications on religious education across the country.

With inputs from agencies

)