On November 16 in 1988, Benazir Bhutto shattered barriers to become Pakistan’s first woman Prime Minister and the first female leader of a Muslim-majority nation.

The day also carries echoes from literature and propaganda: in 1849, Fyodor Dostoevsky faced a death sentence that would profoundly shape his writing, while in 1941, Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels published one of his most infamous essays spreading hate across Europe.

Decades later, on November 16, 2001, the magic of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone would cast its first cinematic spell, launching a global cultural phenomenon.

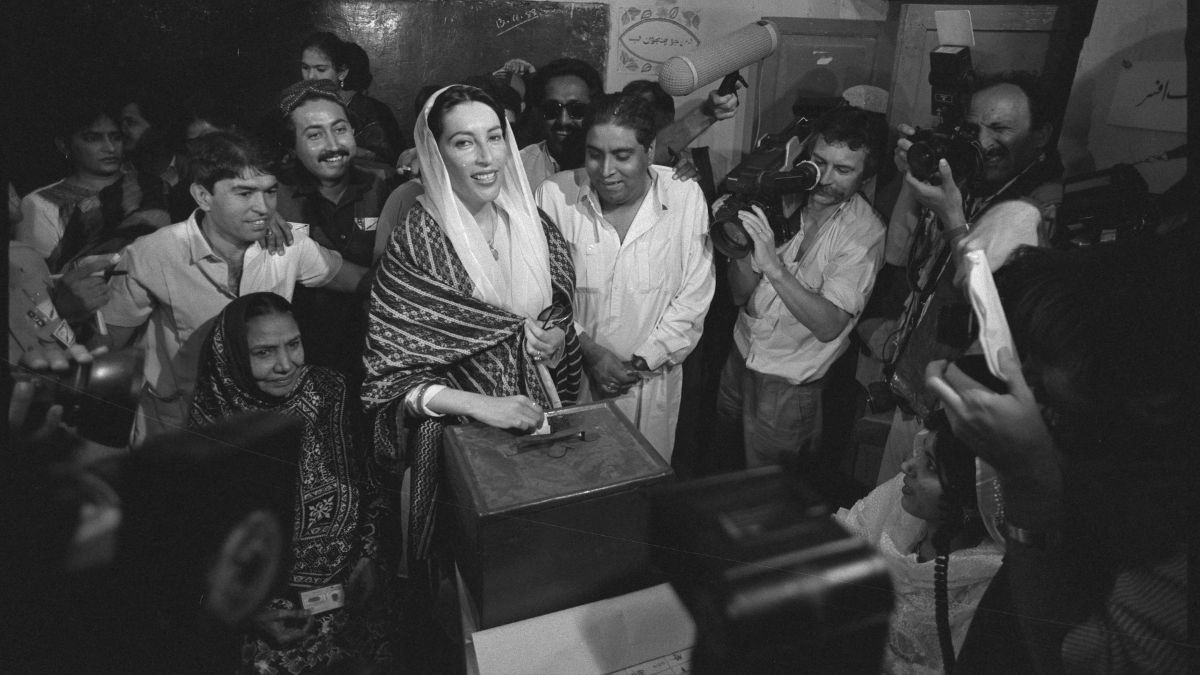

Benazir Bhutto becomes prime minister of Pakistan

In 1988, Pakistan stood at a crossroads.

The decade-long military rule of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq had come to a sudden end following his death in a mysterious plane crash in August.

The nation, long under the shadow of martial law, was preparing for a general election that could redefine its political future.

On November 16, 1988, that moment arrived when Benazir Bhutto, the 35-year-old leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), was elected as prime minister — becoming the first woman to lead a Muslim-majority nation.

Bhutto’s ascent was deeply intertwined with her family’s political legacy. Her father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, had been Pakistan’s prime minister in the 1970s before being overthrown and executed under Zia’s regime in 1979.

Benazir’s return to politics in the mid-1980s symbolised both defiance and continuity — a bid to reclaim democratic governance from authoritarianism.

After years of imprisonment and exile, her campaign embodied the public’s yearning for change.

The November 1988 general elections were held under the banner of partial democracy. Zia’s death had created a vacuum, and Pakistan President Ghulam Ishaq Khan called for a return to civilian rule.

The PPP campaigned on populist and progressive promises — housing, healthcare, and education for all — echoing the ideals of her father’s socialist platform.

Her message resonated particularly with Pakistan’s youth, rural voters, and women, who saw her as a figure of reform and national renewal.

The elections were held on November 16, and the results signalled a clear shift. The PPP won 94 of the 207 seats in the National Assembly — a plurality but not an outright majority.

The conservative Islamic Democratic Alliance (IDA), composed of right-leaning parties, came in second. Despite the fragmented outcome, Bhutto successfully formed a coalition government and was formally sworn in as prime minister on December 2, 1988.

Her victory carried enormous symbolic weight beyond Pakistan. In a world where female political leadership was still rare — particularly in Muslim societies — Bhutto’s success made global headlines.

From London to New York, newspapers hailed her as the “Daughter of the East,” a leader embodying a new era of modernity and female empowerment in South Asia.

In her speeches, Bhutto focused on democracy, women’s participation, and Pakistan’s place in the international community.

“Democracy is the best revenge,” she would later famously declare — a statement that became synonymous with her political journey.

Yet, her premiership was fraught with challenges. The military, still a powerful force in Pakistan’s political system, maintained a wary distance from the civilian government.

Pakistan President Ishaq Khan retained constitutional powers that could dissolve the parliament, effectively curbing Bhutto’s authority. Moreover, her efforts to liberalise the economy, restore civil liberties, and strengthen relations with India faced institutional resistance.

Foreign policy during her first tenure balanced caution and aspiration. Bhutto sought to improve relations with neighbouring India and Afghanistan, both vital for regional stability.

She also reaffirmed Pakistan’s alliance with the United States, especially in the post-Soviet phase of the Afghan conflict. However, internal political disputes and allegations of corruption weakened her government’s position.

By 1990, just two years after her historic rise, Bhutto’s government was dismissed by the president on charges of corruption and mismanagement — accusations that would haunt her throughout her career.

Despite her removal, her influence endured. She returned to power in 1993 for a second term and continued to champion democratic governance until her tragic assassination in 2007 during an election rally in Rawalpindi.

The first Harry Potter film premieres

On November 16, 2001, audiences across the United States and the United Kingdom were introduced to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (released as Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in the UK).

Directed by Chris Columbus, the film marked the cinematic debut of JK Rowling’s globally successful book series.

Starring Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter, Emma Watson as Hermione Granger, and Rupert Grint as Ron Weasley, the movie faithfully adapted Rowling’s 1997 novel, chronicling the young wizard’s first year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

With visual effects, a John Williams score, and a cast of British legends — including Richard Harris, Maggie Smith, and Alan Rickman — the film captivated audiences and critics alike.

The release broke box-office records, grossing over $974 million worldwide and launching a decade-long cinematic saga that would shape global popular culture.

The success of Harry Potter also reinvigorated children’s literature, proving that fantasy stories could achieve massive mainstream success.

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s death sentence

On November 16, 1849, Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky faced a moment that would forever alter his life and work.

Arrested for his involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle — a group of intellectuals advocating for political reform and freedom of thought under Tsar Nicholas I — Dostoevsky was sentenced to death by firing squad.

At the last moment, his sentence was commuted to four years of hard labour in a Siberian prison camp, followed by military service. The mock execution — staged as a form of psychological punishment — left an indelible mark on Dostoevsky’s psyche.

His near-death experience, exile, and the harsh conditions in Siberia profoundly shaped his worldview.

From this ordeal emerged his exploration of morality, suffering, and redemption — themes that permeated his masterpieces such as Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov, and Notes from the Underground.

Dostoevsky’s transformation from a political idealist to a spiritual philosopher was rooted in that fateful November day.

His survival and later literary genius would redefine Russian literature and influence existential thought worldwide.

Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda manifesto

On November 16, 1941, Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, published one of his most virulent essays in the weekly newspaper Das Reich, titled “The Jews Are Guilty.”

The piece reflected the Nazi regime’s escalating genocidal rhetoric during World War II, portraying Jewish people as enemies of civilisation and scapegoats for Germany’s hardships.

Goebbels’ publication came amid the Holocaust’s intensification, as mass deportations and executions were already underway in occupied Eastern Europe.

The article served both as justification and mobilisation — seeking to desensitise the German populace to the atrocities being carried out.

In this essay, Goebbels employed pseudo-historical claims and manipulative language to construct a moral rationale for extermination, directly supporting Adolf Hitler’s genocidal policy.

The November 16, 1941 essay remains a chilling example of how propaganda can weaponise hatred and enable systemic violence.

With inputs from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)