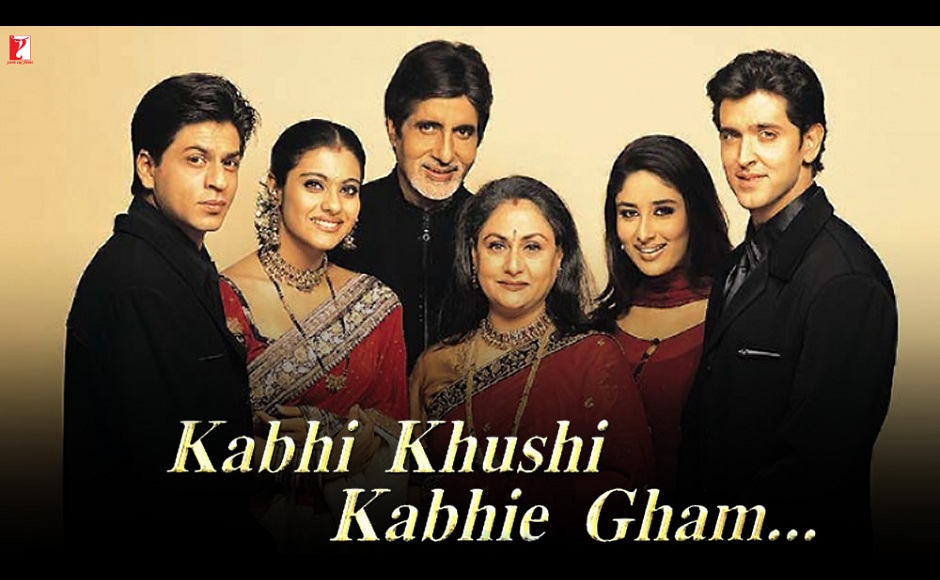

In a scene from Ishq(1997) Harbans Lal played by a bald Dalip Tahil rhetorically asks his younger brother “Jis ghar mein kutte bhi nasal dekh ke pale jaate hain uss ghar ka damaad ek driver ka beta?”. We might call it cringe today but as much as Bollywood espoused love across the boundaries of class, on the ground the reality has remained cruder. Perhaps not as vile as the venomous fathers (the other played by the terrific Sadashiv Amrapurkar) in Ishq, but close. These are men aligned to their goal of generational privilege to the extent that they wish to compound, even their children. It’s what drives them to agree to a cynical pact that love ultimately undoes. But while Ishq’s deafening portrayal of fatherhood turned the father figure irredeemable, there have been others in Bollywood, who have restrained and rejected, relatively gracefully, in the interest of both society and state. The incredulous father has been ever-present in our cinema. From Akbar in _Mughal-e-Azam_ to Mr Raichand in Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham , men have taken it upon themselves to build and hold the mantle of moral fortitude to a level higher than themselves. These are men who believe in the structural relevance of the world around them and seek to learn from it the teachings of everyday morality. Their codes aren’t necessarily militaristic but they do draw the line at the insurgency of caste and class. Both Akbar and Raichand, for example, understand the value of empowering the lower classes, and in fact perforate with exuberance when the opportunity presents itself to display a certain degree of shared vanity. They regale their audiences while withdrawing from their inquests in private. It’s what separates a sense of kingship from that of leadership. Fatherhood is tricky business for it lies at the border of politics and family. It’s a crown of thorns that most men enjoy as much as they detest its burdens. Perhaps Naseerudin Shah’s Masoom was the first real dent into the father figure’s unbridled enthusiasm to play to the white canvas of infallibility. It’s is a tender little film that unknots years of father figures playing overbearing shells of machoism packaged as concern and responsibility. In our cinema, fathers are frequently proven wrong and yet they return with renewed zest to re-impose themselves on the world we live in and the one we wish to imagine. It’s like they are there even when they are not, like the honour of a law-abiding, honest man. This almost imaginary entity all of democracy hinges on idolising. The kind of man that though free must exist within boundaries. Most fathers, therefo [caption id=“attachment_10278241” align=“alignnone” width=“300”]  Amrish Puri in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge[/caption] re, resist and restrict out of design. In post-globalisation cinema DDLJ ’s Amrish Puri and _K3G_ ’s Bachchan, represented both the state and scripture. India, caught in the crosswinds of international exposure and influence was reminded of the metallic core that keeps a ship’s hull together. Keeps it from bursting at the seams even at sea. These father figures might ultimately be proven wrong but that does not discount the value of their reluctance to bend. In essence, fathers became the virtuous chords that connected a generation of seekers to the lodestar of identity and statehood. These fathers couldn’t quite contemplate the inner frictions of their country, but instead chose to look outward at the miasma of influence rather than the gullibility of our own historic beliefs. Love suddenly became problematic not because it crossed internal boundaries but because it seemed vulgarly affected by a depraved counter-culture. Baldev Singh and Shankar Narayan therefore embody incredulity so as protective tarp. Fathers are complex figures to write, shape and essay. In western culture they are seen as the source of unsaid pain, whereas here in Bollywood, they have been cast as obscure entities we scarcely see the vulnerable sides of. Rarely have father figures died on the hills they stood for and it is perhaps a sign of the character’s democratic origins, that even the men who seem and look beyond compromise ultimately bend to the call of the larger narrative. It’s what democracy is perhaps all about, gnawing your way through the system, through its provisional alliances, before you convince the one true power to listen. The fathers of todays’ cinema are bolder, much more talkative and open-ended in their interpretation of society. They don’t intrude as much, sermonise far less and have their own demons to confront with. What started with Masoom some forty years ago, has ultimately been adopted as a way to seek characters that go beyond the temperamental bullies that echoed both the state’s inflexibility and the reckoning of tradition. Today the father figure has mellowed, accepted his place in the larger scheme of untraceable life journeys and retreated to nurturing his own pursuits. They have stuff to do. And its delightfully optimistic, because in her homes, the incredulous ones live on. Like a self-serving security check under the guise of cool and calmness. We just hear less of him. Manik Sharma writes on art and culture, cinema, books, and everything in between. He tweets at Manik1Sharma. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

The incredulous father figure is a complex destination for morality and politics, which is why it closely resembles the nature of both the state and democracy.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)