In the column Let’s Talk About Women, Sneha Bengani looks at films, the world of entertainment, and popular media through the feminist lens. Because it’s important. Because it’s needed. And because we’re not doing it enough. * 2007 was an interesting year for Hindi films. Deepika Padukone and Ranbir Kapoor made their big acting debuts, Madhuri Dixit Nene returned after a hiatus of five years, the Deol father-son trio graced the silver screen for the first time together, Imtiaz Ali released his most successful film yet, and Reema Kagti, Anurag Kashyap, and Anurag Basu made the movie-verse richer with their experimental, realist cinema. In the middle of it all, an adman makes his foray into films. He decides to highlight just how ageist we are as people by exploiting our love for food. If you look at it, the barebones construct of Cheeni Kum is quite banal really. Very daal chawal, if you will. Boy meets girl, they set off on the wrong foot, but soon their steps fall in tandem. A skip, a twirl, some tango, and before they know it, they are dancing to a full-blown symphony. But much like his protagonist Bhuddhadev Gupta, our adman-turned-director R Balki knows how to add zing and zaika and transform even the most ordinary platter into a splendid, sumptuous meal. He takes the rice and adds to it mutton (cooked for precisely 18.25 minutes), ginger and garlic (5-6 gm), shuddh ghee (two spoons), a dash of sour curd, milk (10 spoons), red chili powder and other spices (2 spoons), a generous sprinkling of saffron, and not a single grain of sugar. In doing so, he transfigures the plain, unappetising rice into the finest Hyderabadi zafrani pulao in the world. [caption id=“attachment_10388431” align=“alignnone” width=“640”] Tabu and Amitabh Bachchan in Cheeni Kum[/caption] Balki’s list of ingredients for his delectable potpourri is as invincible as Buddha’s. He injects conflict—his main man is the 64-year-old head chef and owner of Spice 6, London’s best Indian restaurant, whose body hair might be greying, but his head and hypothalamus are as hot as can be. He falls for a 34-year-old software engineer from Delhi whose father is a Gandhian and at 58, well settled into retirement. More than their difference in age, it’s their differing ideologies that cause the clash. Buddha has a full, thriving life in London, which has got richer after a chance encounter with Nina. Meanwhile, Nina’s father—who is six years younger than Buddha—comfortably thinks of himself as a second-hand ambassador car whose day revolves around bhajan, bhojan, and Bhajji (prayer, food, and cricket). Balki then ropes in formidable actors, the best Indian cinema has to offer, to play the people caught in this curious situation. He chooses his favourite superstar Amitabh Bachchan to play Buddha, Tabu for Nina, and Paresh Rawal for her ageist, cricket fanatic father. For that final dash of tadka, Balki equips each of them with distinct quirks and peculiarities, making sure there’s never a dull moment in the film.

Tabu and Amitabh Bachchan in Cheeni Kum[/caption] Balki’s list of ingredients for his delectable potpourri is as invincible as Buddha’s. He injects conflict—his main man is the 64-year-old head chef and owner of Spice 6, London’s best Indian restaurant, whose body hair might be greying, but his head and hypothalamus are as hot as can be. He falls for a 34-year-old software engineer from Delhi whose father is a Gandhian and at 58, well settled into retirement. More than their difference in age, it’s their differing ideologies that cause the clash. Buddha has a full, thriving life in London, which has got richer after a chance encounter with Nina. Meanwhile, Nina’s father—who is six years younger than Buddha—comfortably thinks of himself as a second-hand ambassador car whose day revolves around bhajan, bhojan, and Bhajji (prayer, food, and cricket). Balki then ropes in formidable actors, the best Indian cinema has to offer, to play the people caught in this curious situation. He chooses his favourite superstar Amitabh Bachchan to play Buddha, Tabu for Nina, and Paresh Rawal for her ageist, cricket fanatic father. For that final dash of tadka, Balki equips each of them with distinct quirks and peculiarities, making sure there’s never a dull moment in the film.

However, his masterstroke lies in how he interweaves the film’s title so inextricably with its story. The title Cheeni Kum provides context, furthers the plot, and serves as a philosophical metaphor, adding delicious detail to various aspects, bringing them all together as a homogenous blend. Other than the obvious food references peppered all through the film—Hyderabadi zafrani pulao, coffee, papdi chaat, Cheeni Kum is also an apt description for Buddha, who has a sour temper. It also becomes the reason facilitating a pivotal development in the story—Nina has to cut short her London trip and return to Delhi because of a sudden spike in the blood sugar level of her diabetic father, causing a tumult in her budding romance with Buddha. But most importantly, it’s as if through the film’s title, Balki is trying to tell all women to contain, and question the “sweetness” that has been conditioned into us, courtesy the deeply lopsided world that we live in. For aren’t women sweeter than men? Don’t we give courteous smiles a lot more, find ourselves nodding to things we don’t agree with, tolerating people we can’t stand? Don’t we say sorry and thank you a lot more than is needed? Don’t we try to cover up or suffer for mistakes that aren’t ours? Don’t we keep quiet when we shouldn’t? Don’t we forgive the unforgivable? Women are expected to be sweet. Because sweet is nice. Sweet is palatable. Sweet strengthens the skewed status quo.

It’s not just through the film’s title, it’s also through its women that Balki tells us to keep the cheeni kum. The movie’s three central women—Nina, Buddha’s mother played by an electrifying Zohra Sehgal, and Swini Khara’s Sexy, a six-year-old girl battling blood cancer—are anything but sweet.

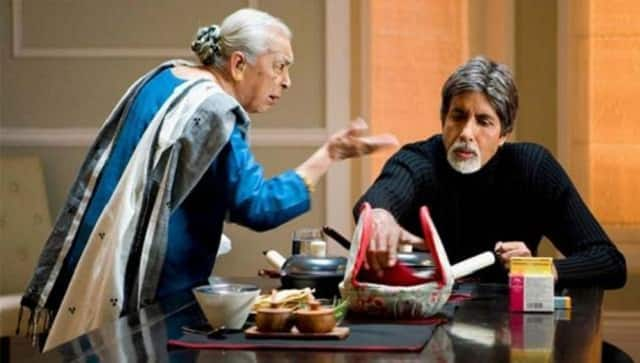

They all have a stark age difference and are at very different places in life. And yet, all three of them have their head firmly placed on their shoulders and they navigate life armed with a razor-sharp tongue and an even sharper wit. They say it as it is. No sugarcoating. No bullshitting. [caption id=“attachment_10795311” align=“alignnone” width=“640”] Zohra Sehgal, Amitabh Bachchan in a still from Cheeni Kum[/caption] Cheeni Kum has multiple scenes that are a testimony to this. Take Buddha and Nina’s first meeting, for instance. Offended by her audacity to send back his restaurant’s celebrated Hyderabadi zafrani pulao, a first in the history of Spice 6, he insults her without even tasting the dish. So confident he is in his and his men’s culinary prowess. As Buddha berates his long, stinging monologue, Nina listens wordlessly, her face changing from surprised to shocked and finally hurt. She leaves, without saying anything. She sends her response the next day, the finest Hyderabadi zafrani pulao in the world, making the cocksure cuisinier double back. Then there’s this scene between Nina and her father in which he declares that he doesn’t approve of her relationship with Buddha. In response, Nina simply tells him that she is not asking for his approval, just informing him. When the conversation blows into a confrontation, he threatens her that he’d not let it happen for as long as he’s alive. She asks, “So when are you going?”

Zohra Sehgal, Amitabh Bachchan in a still from Cheeni Kum[/caption] Cheeni Kum has multiple scenes that are a testimony to this. Take Buddha and Nina’s first meeting, for instance. Offended by her audacity to send back his restaurant’s celebrated Hyderabadi zafrani pulao, a first in the history of Spice 6, he insults her without even tasting the dish. So confident he is in his and his men’s culinary prowess. As Buddha berates his long, stinging monologue, Nina listens wordlessly, her face changing from surprised to shocked and finally hurt. She leaves, without saying anything. She sends her response the next day, the finest Hyderabadi zafrani pulao in the world, making the cocksure cuisinier double back. Then there’s this scene between Nina and her father in which he declares that he doesn’t approve of her relationship with Buddha. In response, Nina simply tells him that she is not asking for his approval, just informing him. When the conversation blows into a confrontation, he threatens her that he’d not let it happen for as long as he’s alive. She asks, “So when are you going?”

There is another fantastic scene between Buddha and Sexy, their last together. He’s just had a fight with Nina. Petulant, he is ready to return to London when Sexy calls. On finding out that things have gone awry, she chides him matter-of-factly, “You must have said something in anger,” and then adds, “Whoever is with you, is doing you a favour” and grounds him in no time. When he asks her if he’s that bad, she quips, “No, it’s just that everyone else is really nice.” Or take Buddha’s mother. When he calls the food she cooks for him worse than what’s served in Tihar jail, she asks him to eat at his famous restaurant instead. She doesn’t fear being called a nag; she pointedly pesters him each day to go to the gym. He doesn’t listen to her until he finally does. On the surface, Cheeni Kum is about an NRI chef finding love at 64. But a closer viewing, and you’ll know—it is about so much more. At its core, it asks you to keep sugar out. Because it spoils—whether it be coffee, Hyderabadi zafrani pulao, or our health. When not reading books or watching films, Sneha Bengani writes about them. She tweets at @benganiwrites. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

)