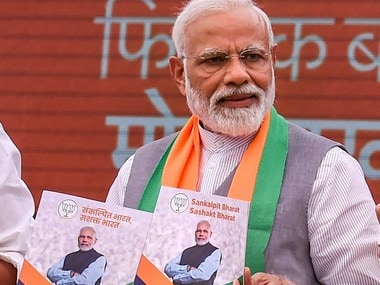

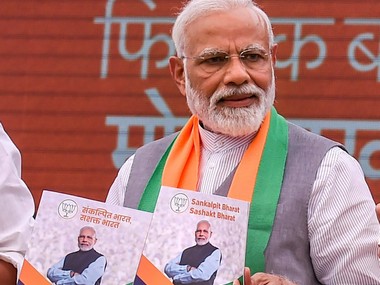

Election manifestos are like good dreams. It doesn’t matter if the promises made in them are implementable or not, what matters is whether they are easy to sell to the voters at large. After the Congress party’s manifesto, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) recently released manifesto, also works well on the dream front. The manifesto promises a whole host of things (like the Congress manifesto) without really bothering to explain, where is the money to implement the promised things going to come from. Or whether the Indian government has the institutional capacity to be implementing the promised things. And that’s why it’s like a good dream, which is easy to dream up, but difficult to execute. Let’s take a look at this pointwise. 1) The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana will be implemented for all farmers. Currently, it is only available to farmers who own up to two hectares of land. If we look at the Agriculture Census of 2015-2016 (published in 2018), the total number of agricultural households in India stood at 14.57 crore. Over the generations, as the agricultural land has been divided, the number of agricultural households in the country has gone up. Looking at the past trend, it is safe to say that the total number of agricultural households in 2019-20, the current financial year, will be at least around 15 crore. At Rs 6,000 per household per year, this works out to an annual outflow of Rs 90,000 crore for the government, under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana. [caption id=“attachment_6411161” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Prime Minister Narendra Modi releases BJP’s manifesto. PTI[/caption] The government has already budgeted Rs 75,000 crore for small and marginal farmers, who are currently eligible for this scheme. Hence, finding the remaining Rs 15,000 crore so that all farmers get Rs 6,000 per year, should not be very difficult. But the question that remains is why should a large farmer, who does not have to pay income tax and gets subsidised fertiliser, get money from the government? 2) The manifesto promises Rs 25 lakh crore to improve the productivity of the farm sector. Again, this is necessary, given that the average Indian farmer only makes a fraction of the money made by the average Indian non-farmer. Even though close to 46 percent of the workforce works in farming, the sector on the whole only contributes around 14.3 percent of the total economic output in the country. This tells us that the sector is terribly unproductive. There is an important need to improve the current agriculture marketing set up all across India, and free the farmer from the chains of the _mandi_s. Also, the proportion of agriculture in the economy has been falling year on year. In 2004-05, the sector used to form 22.6 percent of the economy.

Given that the sector is hugely unproductive, it has a huge amount of disguised unemployment, with many more people working in it, than what is actually required. In this scenario, it is important to improve the productivity of the sector. Having said that, Rs 25 lakh crore is not a small amount of money. To give a sense of comparison, the total expenditure of the government of India in 2018-19 is expected to be at Rs 24.6 lakh crore. Hence, the question, where is this money going to come from. The BJP manifesto like a good dream does not get into the details.

- The manifesto promises to “provide short-term new agriculture loans up to Rs 1 lakh at a zero percent interest rate for 1-5 years on the condition of prompt repayment of the principal amount.” This innocuous promise will have huge repercussions on the government expenditure, if implemented. As mentioned earlier, there are around 15 crore agricultural households in the country currently. Even if around half of the households make use of this scheme, it will involve giving a total loan of Rs 7.5 lakh crore. Of course, the government isn’t going to give out this money from its own pocket, it will expect the public sector banks, already down and out, under a huge amount of bad loans, to give out these loans. Bad loans are loans which haven’t been repaid for a period of 90 days or more. The interesting thing is that the total agriculture credit in India as of March 2019, stands at 10.93 lakh crore. If we look at the data for the last five years, the banks on the whole, have given out around Rs 85,000 crore of agricultural credit each year, on an average. The government wants the public sector banks to give out loans of Rs 7.5 lakh crore as interest-free credit to the farmers. The question is, do banks have the distributional capacity to lend such a huge amount of money? Also, the banks will need deposits to give out loans. Where are the banks suddenly going to get such a large amount of money as deposits to give out as loans? Will this not push up the interest rates? Further, with so much lending needed to be carried out, how will banks maintain quality of the lending they are carrying out? 4) The manifesto also promises to make a capital investment of Rs 100 lakh crore by 2024 in the infrastructure sector. Nobody can argue against this. India’s physical infrastructure needs a lot of improvement. We need better roads, railways, ports, airports and so on. Having said that, Rs 100 lakh crore isn’t exactly small change. It’s more than four times the annual expenditure of the government of India in 2018-19. The total capital expenditure of the government of India in 2018-19 had stood at Rs 9.61 lakh crore. The investment of Rs 100 lakh crore in infrastructure is many times more than this amount. Again, where is all this money going to come from? Also, more importantly, does the government have the institutional capacity to spend such a large amount of money in such a short period of time? It is worth remembering that there is no free lunch in economics. Someone will have to pay for all this. Does this mean higher taxes? But the manifesto also commits to “simplifying and lowing tax rates”. (The writer is an economist and the author of the Easy Money trilogy.) Click here for more details on BJP's manifesto for Lok Sabha Election 2019

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)