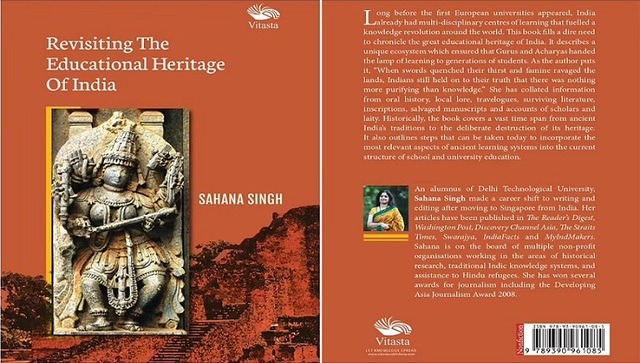

We often hear snippets of how India had led the world in education for centuries, how students from many faraway lands sought the ancient universities in India, how they spent a considerable amount of time here, and how Indian scriptures were highly valued and in great demand among scholars from near and far. Every now and then, we also hear of German universities researching Sanskrit texts, of schools in the UK teaching Sanskrit to their children, and of computer scientists studying the ancient Sanskrit grammar code by Panini to further their research in such areas as Natural Language Understanding (NLU) and Knowledge Representation. When Prof Manjul Bhargava, Professor of Mathematics at Princeton University, won the prestigious Fields Medal, the first Indian-origin mathematician to do so, he attributed his inspiration to the classic works of ancient Indian mathematicians. All this makes us wonder: What have our ancient rishis left behind? What wisdom do our scriptures hold? Why are we unaware? Where could our children possibly learn about the rich knowledge of this land, since our schools definitely do not impart any of it! What are we missing out on? It is this gap that Sahana Singh’s new book, Revisiting the Educational Heritage of India, strives to fill. She has laboriously referenced more than 230 sources and has put together this compendium in less than 250 pages. While the book packs in extensive information, it is also written in an easy narrative fashion that makes for a pleasurable read. In 2017, Singh published a long essay in the form of a small book The Educational Heritage of Ancient India: How an Ecosystem of Learning Was Laid to Waste, where she provided an overview of India’s education system down the ages from ancient to modern times. While this book set off various conversations about our educational heritage, Singh received many requests to expand more on the topics in the book. It was evident that the audience wanted more. Two things became clear: a) There was a huge thirst for knowledge about India’s educational heritage; b) The conspicuous lack of information and reading material for popular consumption. So she spent the next four years reading, researching, and writing to bring out the detailed version. This book covers a vast period of time from ancient India’s traditions to the deliberate destruction of its education to the post-Independence education that did little justice to the Indian heritage to what can today’s India learn from its ancient systems. “Long before the first European universities appeared, India already had multidisciplinary centres of learning that fuelled a knowledge revolution around the world” reads the blurb at the back of the book. The author furnishes a wealth of information about the ecosystem that ensured that gurus and acharyas taught their knowledge to generations of students in ancient India with its world-class educational centres. She has uncovered 80 traditional centres of advanced education in India from about 6th BCE onwards and has plotted them all on the map that serves as a quick visual guide. These include the famous Nalanda, Takshashila, Ujjaini and the many lesser-known ones like Telhara, Ennayiram, Ahichhatra and others. Singh elaborates about the disciplines taught at the universities as well as the flourishing support structure that bolstered education and the pursuit of knowledge, both among scholars as well as students. Teachers were hugely respected and supported by the royalty as well as the citizens. We learn that students used to travel long distances, far from their families, to go to the best universities of their time. [caption id=“attachment_10251601” align=“alignnone” width=“300”]

The Educational Heritage of Ancient India: How an Ecosystem of Learning Was Laid to Waste by Sahana Singh[/caption] She explores the guru-disciple tradition and the ethos of Brahmacharya among students. What did their lifestyle entail? Was a student’s life only about discipline, strict routine, hard work and lack of sleep? Or were their lives enriched with holistic development? The book discusses all this and more and provides insights into the memory-training methods that contributed to giant memories among students and scholars. Educational games such as snakes and ladders, chess, playing cards were employed to teach the nuances of ethics, strategy, warfare, foresight and more. The board game, snakes and ladders, incorporated simple lessons in spiritual advancements. Students learned that developing vices was detrimental. Not just that, virtues were rewarded! Now, ‘snakes and ladders’ is only a number game. How did it come to be so tepid? The book reveals this and many other stories. The story of the knowledge revolution that emanated from India is recounted in great detail. Singh also provides a reference graphic depicting the kind of disciplines that were carried to the different parts of the world. This is perhaps the first time that we are seeing this information in a concise graphic.

The Educational Heritage of Ancient India: How an Ecosystem of Learning Was Laid to Waste by Sahana Singh[/caption] She explores the guru-disciple tradition and the ethos of Brahmacharya among students. What did their lifestyle entail? Was a student’s life only about discipline, strict routine, hard work and lack of sleep? Or were their lives enriched with holistic development? The book discusses all this and more and provides insights into the memory-training methods that contributed to giant memories among students and scholars. Educational games such as snakes and ladders, chess, playing cards were employed to teach the nuances of ethics, strategy, warfare, foresight and more. The board game, snakes and ladders, incorporated simple lessons in spiritual advancements. Students learned that developing vices was detrimental. Not just that, virtues were rewarded! Now, ‘snakes and ladders’ is only a number game. How did it come to be so tepid? The book reveals this and many other stories. The story of the knowledge revolution that emanated from India is recounted in great detail. Singh also provides a reference graphic depicting the kind of disciplines that were carried to the different parts of the world. This is perhaps the first time that we are seeing this information in a concise graphic.

What is India’s educational heritage? A review of Sahana Singh’s new book

Chitra Aiyer

• January 2, 2022, 14:48:18 IST

Long before the first European universities appeared, India already had multidisciplinary centres of learning that fuelled a knowledge revolution around the world. So, why this mess now?

Advertisement

)

Storytelling was employed efficiently via songs, dance, drama, puppet shows, paintings. The Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas, short stories from the Panchatantra, Hitopadesha, Jataka were all seamlessly woven into the study. One of the chapters I enjoyed reading is ‘Distilling worldly wisdom through fables’. The fascinating history of the Panchatantra and how it travelled to faraway lands would make for a great book on its own! Given our own childhood memories associated with the stories in the Amar Chitra Katha, this chapter is likely to leave a warm fuzzy feeling in your hearts. If our education and knowledge traditions were so superior, why are we now left at the behest of subpar schooling? Who is responsible for the destruction? Singh dedicates chapters both for the assault under the foreign Islamic marauders and the strategic uprooting during the British colonial rule. The decimation of India’s rich educational heritage is tragic, yes. But what have we done about it post-Independence? Almost nothing and so also why we confront our ignorance now. An immediate first step is for us to become aware of our inheritance. This book provides a much-needed detailed summary and makes for a must-read for all Indians and especially so for our young. This is Singh’s big foundational step in the field of our educational heritage. Each of the sub-topics has the potential to be an independent book backed by a significant amount of research. Singh herself hopes the subject matter of this book inspires researchers in a multitude of disciplines and attracts grassroots efforts towards cultural revival. Read all the Latest News

, Trending News

, Cricket News

, Bollywood News

, India News

and Entertainment News

here. Follow us on

Facebook

,

Twitter

and

Instagram

.

End of Article