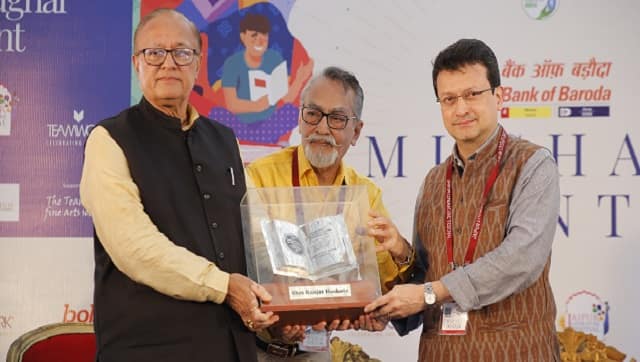

Ranjit Hoskote is a literary powerhouse, known for writing poetry that is finely crafted with a skilled hand, and informed by decades of immersion in art, philosophy, music, and history. At the Jaipur Literature Festival this year, he received the seventh Mahakavi Kanhaiyalal Sethia Poetry Award. Hoskote’s contributions as a poet extend across books such as Zones of Assault (1991), The Cartographer’s Apprentice (2000), The Sleepwalker’s Archive (2001), Vanishing Acts: New and Selected Poems 1985-2005 (2006), Central Time (2014), Jonahwhale (2018), The Atlas of Lost Beliefs (2020), and Hunchprose (2021). Hoskote’s poems have been translated into German, Arabic, Hindi, Swedish, and Spanish. He has translated the poetry of Vasant Abaji Dahake from Marathi into English, and the poetry of Lal Ded from Kashmiri into English. The award is named after Sethia who was a poet, freedom fighter, social reformer, philanthropist, and environmentalist who has authored 42 books in three languages – Hindi, Urdu, and Rajasthani. Hoskote was unanimously chosen for this award by a jury comprising Namita Gokhale, Sanjoy K Roy, Nirupama Dutt, Jaiprakash Sethia, and Siddharth Sethia. We bring you an exclusive interview with Hoskote, who graciously responded to our questions about his long and fulfilling journey as a poet nourished by other poets. How do you feel about receiving the Mahakavi Kanhaiya Lal Sethia Award? I feel blessed to have received this award, especially because it carries forward the legacy of a major poet who contributed to three languages – Rajasthani, Hindi, and Urdu. As a writer who prizes multilingual experience and its capacity to expand our horizons, I read this as a particularly auspicious sign. It is also marvellous to take my place in a sequence of laureates that embraces poets whose work I admire and respect – Rituraj, Jayanta Mahapatra, Anamika, Surjit Patar, Rajathi Salma, and Arvind Mehrotra. This award is not for a specific book of yours but for your entire body of work as a poet. How do you look back at your own evolution as a poet from the first book to the most recent one, in terms of form and content? It has been 31 years since my first collection of poems, Zones of Assault, was published. I was 22 at the time. Over these decades, I would like to think that my poetry records a process of engagement with the world in all its dimensions of love and war, turbulence and exhilaration, the pulse of animal vitality and the thrum of planetary extinction. My poems have always been woven around the figures of the survivor, the pilgrim, the nomad, the castaway, the refugee. My attempt has been to craft a solidarity between the singular vulnerability of the individual and the shared anxieties of the multitudes. How can the fragmentary lyric poem become more porous, more polyphonic, more responsive to diverse voices and predicaments? That has long been my key formal question. For the rest, my poetry continues to try and balance between hardy optimism and bleak wisdom, pivoting around the question of legacy – what will outlast us, what can we make that will speak of us long after we have returned to air and dust? When you began your journey as a young poet, who and what gave you courage and inspiration? Which spaces, forums, and communities did you find the most nurturing? What gave me immense assurance, from my childhood onwards, was the active support of my parents, who were devoted to the arts. To them, the idea of a life in the arts was not a strange or disconcerting notion. On the contrary, they were convinced that I should follow my early aptitude for the visual arts by going to art school. In the event, as I began to write, they were very happy with the direction I chose to explore. I was also fortunate in having the profoundly generous poet and critic Nissim Ezekiel as my first guru, my first mentor. Despite the difference in our poetic emphases, already evident very early on, Nissim opened doors for me, and was immensely supportive. My first collection of poems was published under his aegis. The PEN All-India Centre, which he directed, was a hospitable and sustaining ethos, as was Poetry Circle, Bombay, which I joined shortly after its foundation in December 1986, and in the evolution of which I was to play a key role during the late 1980s and the early 1990s. The connections that were formed in these forums 35 years ago flowered into lifelong friendships for me, especially with Arundhathi Subramaniam and Jerry Pinto. What connections do you see between your work as a poet, and your practice as a critic-theorist-curator? Whether in poetry or in curatorial practice, I trust the miracle of the pattern, as it announces itself through the generative interplay between intuition and concept, affect and discourse, the familiar and the unpredictable. In my work as a poet as well as in my work as a critic and theorist, I am fascinated by the manner in which art produces the possibility of a world aslant, a world otherwise, an imaginary that is sumptuous in hope and vibrancy, which opposes the world as it is, a world of dullness, injustice, and oppression. [caption id=“attachment_10486011” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Ranjit Hoskote receives the Mahakavi Kanhaiyalal Sethia Poetry Award at Jaipur Literature Festival 2022[/caption] Where do you look for validation and critique when you write today? Who are the peers – in India and elsewhere – that you share first drafts with, and seek feedback from? I never share first drafts with anyone. My method is to work away quietly, sometimes for years and even decades, on notes and fragments – episodic bursts of utterance or observation that I gradually craft into shape. Once I feel substantially confident, and have arranged my poems into a sequence, usually into a pre-manuscript constellation, I share selections from it with a small circle of friends and readers, fellow writers in various genres. This circle includes my wife, the theorist and curator Nancy Adajania, and my close friends the novelist Ilija Trojanow in Vienna, the essayist Sukhada Tatke in Edinburgh, and the poet and translator Jürgen Brôcan in Dortmund. For the book that became The Atlas of Lost Beliefs, the response and advice of James Byrne, poet and anthologist in Liverpool, were invaluable. My writerly process is deeply sustained, also, by ongoing conversations (not confined to poetry) with fellow poets whom I trust deeply, and the reading of their work in poetry and other domains – among them, Ruth Padel, Forrest Gander, Steven J Fowler, Arundhathi Subramaniam, Jeet Thayil, Sudeep Sen, Sampurna Chattarji, Mustansir Dalvi, Tishani Doshi, Nikola Madzirov, Anjali Purohit, Meena Kandasamy, Vinita Agarwal, Suhit Kelkar, Sarabjeet Garcha, Subhro Bandopadhyay, Priya Sarukkai Chabria, and Alvin Pang.

The activity of writing poetry might be solitary, but it is supported by a community – even a family – of fellow writers and readers.

One of your biggest contributions to world literature is your translation of the poems of Kashmiri poet Lal Ded, also known as Lalleshwari. You laboured over it for several years. What did the process of translating her do to you, viscerally? I ask because she is not the easiest to translate, and because of your personal connection with Kashmir. Thank you, this is very kind of you. During the two decades that I devoted to translating Lal Ded’s vaakhs, I found myself transformed by the process. I became deeply responsive to the mystical quest, to the possibility of combining such an individual quest with more collective questions of solidarity, justice, and freedom. I became more sensitive to the texture and gradient of the many individual voices that speak to us and through us. And as my consciousness expanded to attune itself to such differences, so too did my poetry change, to become more accommodating of the polyphonic diversity with which the world addresses us. As I have written in the Introduction to I, Lalla: The Poems of Lal Ded, the project began in my individual quest as a 22-year-old person to reclaim an ethnic past from across the gulf of diaspora. But before long, this purely personal emotional investment yielded place to a far more expansive empathy with Kashmir’s long history of anguish and exhilaration, and the sufferings of its people in the present, whether at home or in the multiple waves of diaspora. Who are the other poets that you wish to translate? What draws you to their poetry? For the last few years, I have been working on the poems of the great Urdu poet, Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810). In his work, I find myself attracted to an intimate feeling of contemporaneity – he struggles with the effects of political turbulence, finds himself navigating conditions of displacement, tries to make sense of a chaotic world. I delight in his lavish linguistic richness – the language in which he writes, which we call Urdu, and he himself called ‘Hindi,’ celebrates the dynamic continuum of Khadi Boli, Farsi, Braj, and Arabic. The glory of Mir’s robust and inventive language defies and resists the communal bigots who seek to constrain Urdu within a religious identity or stigmatise it as being of foreign origin. Mir’s poetry reminds us of the complexity of the human adventure, through its phases of despair, passion, ecstasy, and epiphany. Mir’s poetry also reminds us of what is truly germane to being ‘Indian’ – the only real way to be Indian is to be kaleidoscopically diverse and confidently open to a plurality of cultural energies. [caption id=“attachment_10486041” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Ranjit Hoskote[/caption] How would you describe your political commitments as a poet writing at a time when ideological lines are sharply drawn, and there is little attempt to dialogue or even hear in the first place? I am committed to a liberal and Constitutional political framework based on inclusiveness, equity, and solidarity. I am a pluralist in culture and matters of belief, happy to practise my own spiritual quest and happy for others to practise theirs, without calling for the primacy of any one over the others. I am utterly opposed to all forms of bigotry, and denounce the weaponisation of cultural differences and the politicisation of religion into a belligerent, annihilatory religiosity. All culture is confluential and nourished by the coming together of dissimilar impulses. All religions have been sustained by the contributions of multiple sources and lineages. The quest for a singular origin, for doctrinal purity and dogmatic practice, is a lethal quest. Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, journalist, commentator, and book reviewer. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)