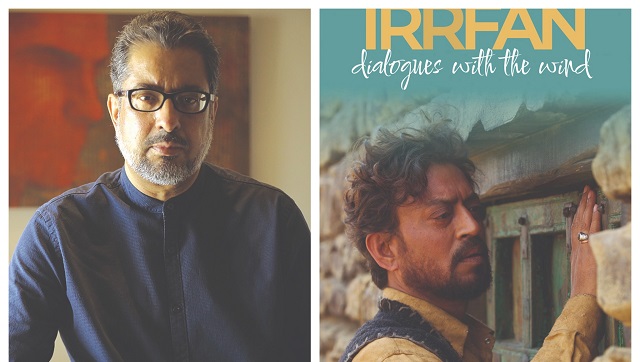

Perhaps many lamented the passing, in 2020, of actor Irrfan Khan , he of the mesmerising eyes and intense yet quiet screen presence, whose acting won accolades in film industries in India and abroad, and whose filmography may have made him one among India’s most acclaimed actors. Impressive as it is, Irrfan’s track record isn’t the theme of the memoir. What is memorialised is the filmmaker’s recollections of his talented, driven, introspective friend whom he directed in two films, Qissa: The Tale of a Lonely Ghost and The Song of Scorpions. And what a memoir it is, at places impressionistic and at places meditatively analytical, and always immersive and generous with insight. It is to address the author’s grief at having lost his close friend that the book is tasked with. Irrfan is remembered in a way only the author could be privy to. The impression we get is he saw a side of Irrfan, Irrfan’s thinking and feeling, his being, that few or none have. These memories he couches as artistic revelations, and as impermanent things go, the revelations are now memories.

It’s haunting and beautiful, the author’s narration of times gone by which were spent in the company of Irrfan; “a celebration and an elegy”.

The book begins when the author flew to Mumbai to find actors for Qissa, and here he met and bonded with Irrfan. They discovered they had a common love, which was for the qawwalis of Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. The author recalls Irrfan saying, “Nusrat Saab mere Alladin-walleh djinn hain! He fulfils the one wish we all have living in a city like Mumbai: to not die with unfulfilled dreams in this city. And Nusrat Saab, of course, grants that wish, who can stay unhappy listening to him?” So the qawwalis soothed Irrfan, but there’s much to read between the lines here about Irrfan’s ambition, his longing to realise his dreams, which perhaps made him suffer. Irrfan was persuaded to join the film’s cast by the author, and as they worked together he and the author became fast friends. Here we are given insight into the director-actor relationship. With feeling, the author writes: “[C]asting an actor carries the same danger as falling in love. You share your deepest vulnerabilities, the growth or ruin of your work, your life and your future with someone else… I knew that as a director, I would have to choose between my reveries and my image of the actor, my hopes about the actor’s possibilities – and the actual person. That is the joy and peril kindling within a director’s nervous system unrelentingly. Who, really, is this person I have decided to entrust with my life?” Who, really? This question would gain deeper dimensions as the author observed Irrfan while shooting Qissa in Punjab. We are told, “… I watched him with the tenderness and reverence we all feel in the presence of anyone possessed by an unappeasable passion”. This passion is not described in so many words, and we are left to gain a sense of it in subtext. [caption id=“attachment_10552471” align=“alignnone” width=“640”] Anup Singh, Irrfan Khan during a film shoot[/caption] The author is describing his feelings here on seeing Irrfan “singing the dialogues of the film” while walking in circles in a grove of trees, in order to make himself comfortable with the Punjabi-language dialogues. In the author’s words, “He seemed to be conversing with ghosts residing in that grove”. Irrfan comes across as one who communed with his lines of dialogue, and how strikingly it is described: “While propelling these sound elements into play, the hope was that this play would also bring his whole being and the world into play: an emotion might rise or ebb faster or hustle unforeseen towards another, a newborn impulse might animate an inexplicable stance in relation to an object, a colour, the sky. Everything becomes sensuous, sentient as the sounds initiated new relationships”. We are told of the time when Irrfan became highly strung while pondering over a scene that brought out the darker shades of his character, the main character in Qissa. In the scene, Irrfan’s character “brutally thrashes his three daughters believing them responsible for his son, Kanwar’s grievous accident. This is where Kanwar is twelve years old”. We are told the scene became too real: Irrfan’s onscreen wife, Tisca Chopra, “broke through the latched door with such force that she almost slammed into Irrfan. He swung and instinctively shoved her back. Tisca flew, stumbling backwards, and crashed into a bureau, shattering it. She collapsed to the floor”. Irrfan helped her up, we read, and she fainted. Yet, soon after, she concealed her pain and gave yet another take. Thereafter she was taken to hospital with bruises and injured muscles. Readers who aren’t from the film industry will get a flavour of the many things actors do to embody characters and negotiate nuances of collegial intimacy with their co-actors. Especially Irrfan. We are told how the cast of Qissa prepared for their parts, including how they became comfortable with one another. For instance, we are told of an acting exercise involving contorting the body in various shapes, in which a female actor’s legs went “scandalously apart and her long kurta steadily [rose] up her legs. Just as I’m going to call out to her, Irrfan jumped down from his position, went around her and held her dress down for the duration of the exercise… ‘We could see your panties,’ Irrfan said. ‘No! Really? I don’t believe you! Tell me the colour.’” The cast had a back-and-forth guessing the colour, which evoked laughter, and the awkwardness that had built between Irrfan and his co-actors was replaced by a sense of ease. Their reticence and bashfulness with him vanished. The author also mentions a rehearsal in which Irrfan, rehearsing for The Song of Scorpions, was on edge with actor Golshifteh Farahani as a means to evoke in her a particular, unsettling feeling. There are places where the author’s remembrances become particularly lyrical. In describing shooting for The Song of Scorpions, amid sand dunes in Rajasthan, the author brings to us a few memorable scenes: the shooting location being overflown by a flock of Siberian cranes, forcing a break in shooting, which Irrfan punctuated by bringing out a kite and flying it into the flock, which responded to it by swerving and playing with it in the open sky. At this point the memoir becomes travelogue as much as anything else, which too is enjoyable. In writing about Irrfan, the author indirectly tells us about himself and how he thinks, which is inevitable as memoirs go. Extremely instructive is the author’s describing, in a few key passages, a large part of his creative process. For instance, this account of how the script of The Song of Scorpions was written: “(The film) had shaped itself from a nightmare that had been besieging me since we all had been sickened and appalled by the news of the rape of a young woman, Jyoti Singh, in a moving bus in Delhi in 2012… [C]ertain images began to recur in my sleep: bright sunlight and a boundless spread of burning sand. And arising from within the blinding flames, a song so beautiful that it even managed to quench the fury of the fire. There, now, in the ash lay an ancient hand-made shawl, blue and purple and blood-red. One night, I saw a figure walking away from another half-buried in sand and I awoke breathless but with the whole story of the film pulsing in my imagination. I grabbed my notebook and a pen and tried to write down the images. Soon, they started to find links amongst themselves and slowly, in bits of dialogues, a disarray of gestures and looks, and a welter of light and dark spreads of landscape, they began to bring forth this tale”. The author couches in well-chosen words what he gauged about Irrfan as actor. He writes, “It was precisely this, his ability to let go of all habitual aspects of himself, not affirm any self, not even the next possibility. His attempt was to create openings that would allow him to wander ceaselessly”. The author sees Irrfan’s striving as spiritual. Or so it seems – for the author acknowledges that memory is mutable. “…I’ve often wondered about what I actually said, felt then, feel now? How much am I imagining as I remember? And even then, even while being as attentive as a director is with an actor, I’m sure there is so much I saw only because I wanted to see it”. This doubt, I suppose, nags all memoir writers, even those who have kept daily diaries to consult as needed. It’s unclear if the author kept any, and that’s not important. What works in this book is seeing glimpses of Irrfan’s life (though perhaps changed in memory) that we wouldn’t see otherwise; and the way the author sees the world; and the glimpses we get into the process of filmmaking. The book ends with the author’s last few conversations with Irrfan, whose cancer was advanced. Yet the author, believing “the end was decades away” for his dear friend, made plans with Irrfan to shoot a movie about a man who claims to be possessed by Radha, Krishna’s devotee, and who then dances as her. The author writes that after Irrfan’s passing, memories of him began to infuse the commonplace moments of daily life in Switzerland and France, where the author has lived – “in a cloud’s tenuous tail”, the “gentle curving gesture of a road”, “the hum of the silent house late at night”. It was then, we’re told, the author began writing this memoir. “Slowly,” he writes, “I opened myself to the flickering wisps of memory. Despite the torment and desolation that came along, I wanted to remember now. I wanted to remember him for all the gifts that he brought to my life and work”. In the author’s words, “This book is written with a profound sense of gratefulness for the expansion he (Irrfan) brought to my life”. Reading this memoir, I got the strong sense that being in Irrfan’s company brought to the author a touch of the passionate and the sacred. Suhit Kelkar is a Mumbai-based writer whose journalism, poetry and short fiction appear in India and abroad. Read all the

Latest News ,

Trending News ,

Cricket News ,

Bollywood News ,

India News and

Entertainment News here. Follow us on

Facebook,

Twitter and

Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)