The intricately woven chain-stitch embroidery created by the Mochi community of Kutch , Gujarat carries with it hundreds of years of legacy and almost as many versions of the stories about how it made its way to the western Indian state from Sindh , today in Pakistan. The roots of this textile art can be traced back to as early as the 13th century in the Sindh region in the form of embroidered leather sleeping mats, hawking gloves and other leather items. The craft was so renowned that Marco Polo admired these pieces during his visit in the 13th century. It is undisputed that the skill of embroidering on leather using ‘aari’, the cobbler’s awl, or in simple words - a hooked needle used by the shoemaker community to mend and make footwear and other leather items, was learned from Sindhi leather embroiderers. At what date the Mochi community started embroidering on cloth rather than leather is an unresolved question. One story that tries to answer this is retold in The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi Embroiderers of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection by Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill. The story was first told by Prof LD Joshi in an article of 1966 in the Gujarat journal Pathik, stating that the transfer of knowledge from Sindhi to Kutchi craftsmen occurred during the reign of Maharao Desaiji (r. 1718-41). After seeing the works of Sindhi artisans who were invited to embroider as well as repair the royal tents, Raoshri wanted the craftsmen of his kingdom to learn the art to enhance the prestige of his realm. Despite the willingness of Kutchi artisans to learn, the Sindhi craftsmen denied them any training and the work of embroidery went on full swing in complete secrecy.

In the tent where the Sindhi kaarigars were secretly at work, entry was strictly forbidden. The plucky Kutchi kaarigars found a way out-they would drive tiny holes into the tent cloth and glimpse the design from a distance with one eye till they could learn the technique of Sindhi workmanship as it took shape on the tent walls. With abundant patience and painstaking labour, they dispossessed the Sindhis of their art. Thereafter, the art flowered with Kutchi talent and dexterity. Within a short time, the Sindhi artistry appeared coarse before the finesse and fineness of the Kutchi stitch-craft.

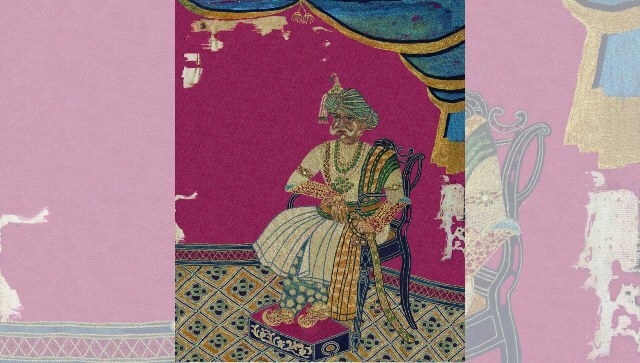

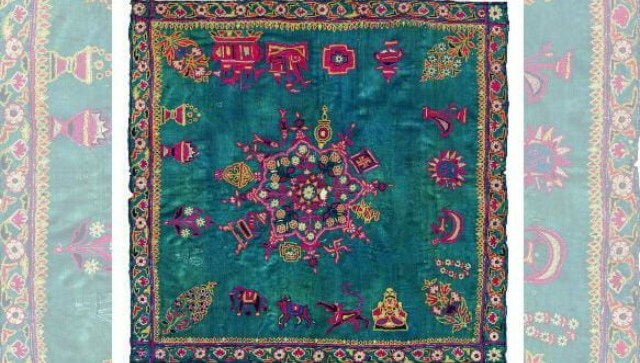

Even though the dates in Prof Joshi’s version are disputed as Portuguese Duarte Barbosa in 1518 and the Dutch Jan Huyghen van Linschoten in 1585 have mentioned Kutchi artisans embroidering on cloth as well as leather, this small anecdote recalled by Crill in the opening essay of her book is one example of the dexterity, wit and skills of the shoemaker community of Kutch. The unique craft of chain-stitch embroidery made a level more special by the Mochi community is a part of The Art and People of India (TAPI) Collection created by Praful and Shilpa Shah. [caption id=“attachment_11099461” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Portrait of Maharaja Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar of Mysore (1794-1868). Satin silk embroidered in chain stitch with silk thread. Kutch, circa 1860. (Niyogi Books)[/caption] The exquisite chain-stitch embroideries of Gujarat’s Mochi community are found in museums and private collections the world over, but the origins of the Mochis and their craftsmanship are rarely explored. The work done by Shah and Crill in curating the equally beautiful and well-researched book shows how the Aari work reached the royal courts throughout the nation and markets across the world solely for being alluring in a way that was unprecedented using a skill that was unparalleled. Many of the pieces in the TAPI Collection of textiles are linked on one side to Gujarati royal families, and on the other to the skilful, indigenous lineage of Mochi craftsmen and women who were commissioned to create these exquisite embroidered items. [caption id=“attachment_11099471” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Jain chaklo (ritual cloth) with Mahavir’s mother Tirshala’s Chaud Sapna (fourteen propitious dreams) and Ashtamangala (eight auspicious symbols). Satin silk embroidered with a needle n chain stitch and herringbone stitch with silk thread. Kutch, late 19th/early 20th century. (Niyogi Books)[/caption] Essays written by Crill and Shah, which paint a picture almost as mesmerising as the accompanying photographs of the chain-stitch embroideries, provide the background of the Mochi community, their work and bring new ideas to fore about the origin and practices of the craft. Crill makes special mention of dado panels on the walls of the Aina Mahal in Bhuj, built around 1750. The superbly embroidered dado panels are an “amalgam of Mughal-style tent panels, with flowering trees shown beneath a cusped arch, separated and bordered by floral meander patterns, and embroideries made for export to Europe for use as wall- and bed-hangings, which frequently show an expric flowering tree rising from a rocky mound.” The catalogue of images displays a wide range of exquisitely embroidered pieces ranging from Jain manuscript covers to portraits, items of clothing, fans, and furnishings, such as floor spreads, wall hangings and tent panels.

The furnishings were mainly hangings, which could be used to decorate either a domestic interior or a religious one. Embroideries for domestic interiors included decorations for the sides and tops of doorways, friezes and wall-hangings, as well as decorative objects such as boards for chaupar. These may depict animals and birds, scenes of domestic life or religious themes, Crill writes.

The photographs of the extraordinary stitch work provides both the uninitiated and the enthusiast with a visual guide of the humble craft. The book also explores the closely-knit relationships between different royal houses of the 18th- and 19th-centuries, the Mochi craftsmen, and the practices prevalent at the time.

While elaborate tents and canopies in Gujarat and other parts of India are often associated with marriage ceremonies, it is notable that this is not the case with the Dhrangadhra tent. According to H.H. Jhallesvar Maharaja Jayasinhji, it was never used for marriages as Jhala Rajputs are forbidden to marry under a canopy of any kind.

The tents were used for special meetings between the ruler and revered visitors, including holy men, and for important pujas. The collectible hardcover is a scholarly study of the exquisite art style, the Mochi community, the taste and practices of the royal families from the 18th till 20th century, and how all of these are intricately woven into each other. Published by Niyogi Books, The Shoemaker’s Stitch is available for purchase on online and offline stores at Rs 4,500. Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)