Why do we play games? According to Amitabh Satyam and Sangeeta Goswami, authors of a wonderful new book called The Games India Plays (2022), games fulfil various physical and emotional needs. Physical activity releases endorphins that “give a natural high” and “provide a feeling of well-being”. Moreover, games help us disconnect from “the stresses of day-to-day life”, provide “a sense of achievement” when we win, and cement social bonds between family members, friends, neighbours, and people from different socio-economic groups.

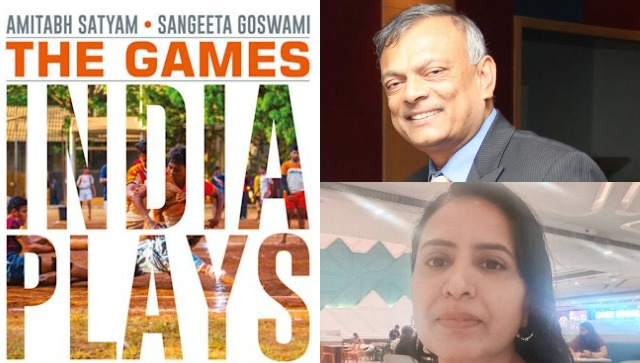

Published by Bloomsbury, this book would appeal to many kinds of readers – people interested in traditional Indian games, those who are looking for a work-life balance, people who like to reminisce about the good old days when they were not stuck to electronic devices, parents looking for activities to keep their children engaged, and teachers who want to energize their school’s boring physical education curriculum with some fresh ideas.

The authors note, “Just like food, clothing and languages, games also grow out of the region’s topography, climate and available natural resources. Games are, consequently, unique to a region, and over millennia, thousands of games have been developed all over the world.”

Amitabh Satyam works in corporate leadership roles, and Sangeeta Goswami is a counselling psychologist who has taught mathematics and sports in schools. They have put together an engrossing book, which looks at 15 traditional games from different states of India in great detail. Each game has a chapter dedicated to it – Lagori, Nondi, Nalugu Rallu Atta, Yubi Lakpi, Gilli Danda, Nadee Parvat, Cheel Jhapatta, Jod Saakli, Vish Amrut, Kho-kho, Langdi, Gella Chutt, Atya-patya, Kabaddi, Pacha Kuthirai. Some of these are played in many regions.

The book is reader-friendly. Every chapter follows a simple structure. After an overview, the authors get into details such as number of players, equipment required, how to play, rules, scoring, caution, skills required, skills developed, life lessons, variations of the game, and a glossary to familiarize readers with game-specific vocabulary that they might need to know. Most of these do not require any financial investment. They can be played without much planning. Some of them are referred to by a wide variety of names documented in the book.

Which of these games did you play as child? I played Jod Saakli, Lagori, Kho-kho, Langdi, and Nadee Parvat. Apart from the ones mentioned here, I played Lukachhupi and Rumaal Dav. I felt safer playing these because boys and girls played them together unlike cricket and football, which were played only by boys in our neighbourhood. Being overweight and effeminate meant that I was bullied frequently by boys. While the authors of this book highlight the positive aspects of games, they do not mention how games often tend to exclude queer and trans children as well as children with physical and psycho-social disabilities.

My favourite game, however, was Antakshari. It was a stay-at-home game that I liked playing with my grandmother during frequent power cuts when we needed something fun to fill the long hours of waiting for electricity. I also enjoyed card games and board games with my cousins during the summer holidays. I agree with the authors that both aspects of games – competition and cooperation are equally important. Games can build confidence, and they can also teach us how to work in a team. Unfortunately, then can also breed arrogance.

From my own childhood, I remember that games were often invented, shared and quickly forgotten. We had no cellphones, so boredom was not easily addressed by visual stimulation. We had to think creatively, use materials that were readily available, and devise something that would quench our thirst for novelty and make sure that we were not creating a ruckus.

When I speak with queer friends, I realize that playing dress-up was a game that many of us played in private. Back then, we just knew that we felt different. We did not have a name for it. Some people tried on clothes of siblings and parents. Some wore their own clothes in a manner that challenged conventional ideas of gender expression. This exploration is perhaps beyond the scope of the book but it is worth mentioning since play and pleasure evoke a range of associations. What gives joy to one can evoke disgust in another, and vice versa.

That said, the book is a remarkable contribution. The authors do a fine job of highlighting how “with colonization, local cultures were destroyed by and large, and games played by the colonizers became mainstream in most of these countries”. This view might be dismissed by some as nationalistic or small-minded but I think that it is worth engaging with. Parents end up spending a lot of money on play equipment either because their children throw tantrums or because the parents themselves want to compete with other parents. This book will direct them to games that their children might be reluctant to play but might eventually warm up to.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, commentator, and book reviewer.

Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

)