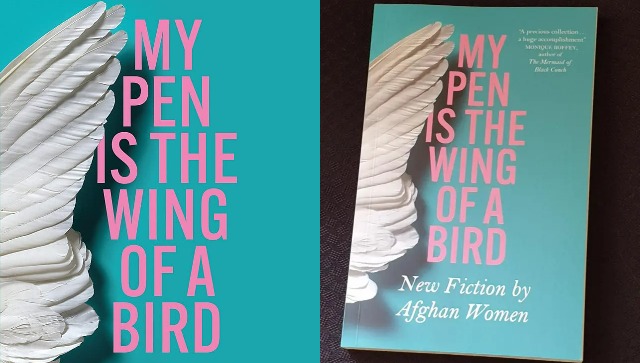

If you are fed up of experts and analysts holding forth on the lives of Afghan women and want to hear directly from those whose lives are at stake, read the book My Pen is the Wing of a Bird: New Fiction by Afghan Women (2022). This is a marvellous collection of short stories by 18 writers, all of whom are Afghan women writing in Dari and/or Pashto. Their work has been translated into English, and the anthology has been published by MacLehose Press.

This book grew out of #WriteAfghanistan, a literary project initiated by Untold Narratives that describes itself as “a development programme for writers marginalized by community or conflict.” Untold Narratives is currently working on two projects – #WriteAfghanistan and #WriteAssamese. The development programme aims to support writers who do not have easy access to mentorship, publishing and distribution platforms that they need in order to be read.

Lucy Hannah, the founder and director of Untold Narratives, writes, “In 2019, Untold put out an open call across Afghanistan, inviting women writers to submit short fiction in Dari and Pashto. Around one hundred submissions came in from all the major cities, along with a few from more rural provinces.” The form of the short story seemed ideal because it can contain “complexity, beauty and truth in so few words, on such small canvases” and it “feels easier to produce” if one does not have “peace of mind, space and concentration”. These are luxuries.

The Afghan writers whose short stories feature in this collection are Maryam Mahjoba, Freshta Ghani, Masouma Kawsari, Fatema Haidari, Sharifa Pasun, Elahe Hosseini, Batool Haidari, Atifa Mozaffari, Anahita Gharib Nawaz, Parand, Marie Bamyani, Maliha Naji, Fatima Saadat, Farangis Elyassi, Fatema Khavari, Naeema Ghani, Zainab Akhlaqi, and Rana Zurmaty. Their stories were translated from Dari and Pashto into English by Zarghuna Kargar, Shekiba Habib, Parwana Fayyaz, Dr. Negeen Kargar, and Dr. Zubair Popalzai.

Through their plots and characters, these stories affirm how diverse women’s experiences are even if they are framed by the common ground of patriarchy, citizenship and religious affiliation. They challenge the tired template of the victim who needs to be rescued, and of the hero who is invincible despite all odds. The women in this book are not entirely without agency; neither are they fully in control. They demand, negotiate, fight, and hustle. They weep in silence. They get beaten and killed. They inspire others through their courage.

Look at how evocative the titles are. Each one is a world unto itself. Here are some examples: “The Most Beautiful Lips in the World”, “Daughter Number Eight”, “What Are Friends For?”, “Please Turn the Air Conditioning On, Sir”, “Khurshid Khanum, Rise and Shine”, and “My Pillow’s Journey of Eleven Thousand, Eight Hundred and Seventy-Six Kilometres”.

When you go through these stories, it would be helpful to pay attention to their literary qualities instead of treating them merely as vehicles that these women use to vent their fears and frustrations for readers in another part of the world. They write not to have their trauma consumed vicariously but to express, create and share with fellow humans. They take the craft of storytelling seriously and deserve readers who do not expect them to perform pain.

My favourite story in this collection is the one titled “Blossom”. Written by Zainab Akhlaqi and translated by Dr. Negeen Kargar, it revolves around two girls – Shaherbano and Nekbakht – who are holding a protest on their school campus with permission from the headmistress. Their plan is to draw the education minister’s attention with their posters and their slogans. They write, “Dear Minister, We Want Teachers! We Want Books!” They have several unflattering things to say about the minister but these cannot be formally noted down.

Shaherbano is a firm believer in the value of education. She wants it not only for herself but for Nekbakht – whose parents want her to marry a boy named Khudadad – and all the girls in Afghanistan. Shaherbano tells her friend Nekbakht, “Now they say the Taliban has changed, but how could they change without reading a book? If a person never reads a book, how can he change? If all our parents were literate, girls like you wouldn’t face these troubles.”

Shaherbano is confident that she herself will become the education minister one day and will “go from door to door, telling families to let their daughters go to school.” She wants to supply them with notebooks and pens that would last until all of them complete their PhDs. Her soaring ambition gives me gooseflesh. It is driven by the desire for collective liberation.

In this book, you will also watch the ripening of fruits and smell the aroma of homemade bread. You will run into the man who gives shelter to an orphan, the woman who is thrown out of public transport, and the boy who stabs his sister’s husband. You will hear the laughter of girls playing hopscotch and the prayers of the boy who wants a lollipop. You will walk past workers trying to keep warm by placing their hands over a fire, and the woman who sells her silver ring to buy rice for her family. You will also meet the woman who wishes for an explosion “to tear her body into pieces and free her from this wretched life forever.”

There are stories here of love and heartbreak, of cruelty and kindness, of despair and hope. If you are attentive, you will also spot references to Rabia Balkhi and Jalaluddin Rumi – the Sufi poets that Afghans proudly celebrate as icons who give them the fuel they need to go on.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, book reviewer, and commentator.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)