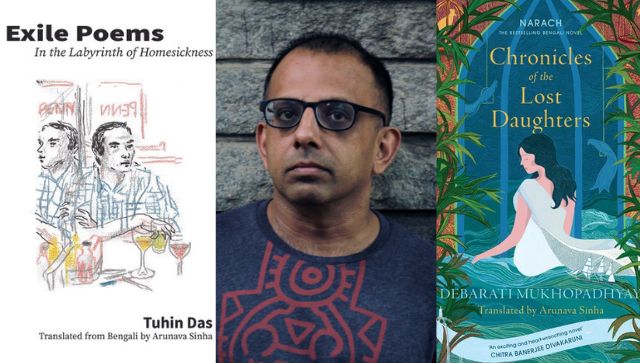

Arunava Sinha , who is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Ashoka University, and co-director of the Ashoka Centre for Translation, translates from Bengali to English and English to Bengali. He has 70 published translations to his credit. This magnificent body of work includes fiction, poetry and non-fiction. Sinha spoke to us about his new translations. Chronicles of The Lost Daughters (2022), published by HarperCollins India, is Sinha’s translation of Debarati Mukhopadhyay’s Bengali novel Narach (2020). Exile Poems: In the Labyrinth of Homesickness (2022), published by Bridge and Tunnel Books in the United States, is Sinha’s translation of Bengali poems written by Tuhin Das, who was compelled to flee his home in Barishal, Bangladesh, in 2016. Das now lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Sinha also spoke to us about his connection with the internationally renowned Tomb of Sand (2021), Daisy Rockwell’s English translation of Geetanjali Shree’s Hindi novel Ret Samadhi (2018), which won the 2022 International Booker Prize for Translated Fiction in London. How did you get involved with translating Narach? Were you drawn to the book because it features historical figures like Rabindranath Tagore, Dr. Kadambini Ganguly, and Nawab Wajid Ali Shah as characters, or was it the writing style? This translation project came to me through Patra Bharati, the Bengali publisher of the novel. The theme of the book, and the material in it, was interesting for me. It is set in the 1880s in Bengal, and is a remarkable account of oppression and cruelty along the lines of caste and gender. It starts with the story of Bhubonmoni, a young widow who is raped by two men. She is told that she is sullied because of sexual assault, and then made to believe that it is her responsibility to absolve herself by having sex with an influential Brahmin man in the village for a whole month. This is mind-boggling, isn’t it? Debarati draws on the social practices of that time to show us what was happening alongside the Bengal Renaissance, which is known for social reform. Yes, women were getting educated and men were supporting them, but that is only part of the story. The novel is quite astonishing. It will make your blood curdle. In addition to the treatment of historical figures, I was also struck by how Debarati engages with the history of indentured labour being taken from Bengal to Surinam. What kind of research did you immerse yourself in for this translation? Did you go to Metiabruz, the neighbourhood in Kolkata where Wajid Ali Shah used to live? I had to look up some references and details but I didn’t have to go anywhere to research. In fact, I translated the novel sitting in Delhi. Honestly, there is no point in going to Metiabruz today to get an understanding of what the neighbourhood used to be like 150 years ago. That said, I have grown up in Kolkata, so I have been to Metiabruz. I know the place. Tell us about your translation of Bangladeshi poet Tuhin Das’s unpublished manuscript. From what I gather, he got death threats for speaking up against the persecution of Hindus in Bangladesh and he has got political asylum in the US. How did you end up translating his poetry? When will the translations be published in India? It has been published only in the US. I don’t know if anyone in India is interested. This translation project came to me from Tuhin Das and City of Asylum, the organization that made sure he got to stay on in the US. When I read the poems in Bengali, I liked them very much, so I agreed to translate them into English. He lives in exile. You can imagine how difficult that must be for a writer or any creative person who is forced to leave the very place that nurtures him. It is tough on many levels – physically, emotionally, psychologically, and the added element of being uprooted and relocated to a place that is very different culturally. You don’t have friends. Your family is back home. There is trauma from the threat that you were living under. All these experiences combine to create an imagination that writes very movingly of exile, home, memory, and the recent history of events in Bangladesh. His poetry is emotional but very tightly controlled. It is direct, spare, unadorned, very contemporary. My approach is clear. I see oppression as oppression, and persecution as persecution. It doesn’t matter who is doing it. You have to stand by the persecuted in a minority-majority situation. What were your interactions like? What did he think of your translations? Tuhin is bilingual. He writes in Bengali but conducts his everyday life in the US in English. He felt that it would be best for someone else to translate his poetry into English. He read my translations, and he liked them. A few excerpts have been published before. He has also written a novel in Bengali. We have spoken about translating it but nothing is finalized. What was it like to be in conversation with the International Booker Prize winner Geetanjali Shree at JLF London 2022? Was it your first public event with her? Answer: She was very much the person of the moment, and it was wonderful listening to her at the British Library. The audience was hanging on to every word of hers. It was a brilliant opportunity for me. We had spoken before on the phone but our first meeting was in London. Daisy Rockwell, who shared the prize this year, credits you for bringing her the opportunity to translate Geetanjali Shree’s Hindi novel Ret Samadhi into English as Tomb of Sand. Why did you recommend Daisy to Deborah Smith at Tilted Axis Press? It’s a long story. A few years ago, I was thinking of how so many excellent books of translation are published in India but almost none of them make it to the Western markets. They stay within India. I asked Seagull Books if they would be interested in creating an India List, which would involve curating books that have already been published in India. I thought of Seagull because they publish not only in India but also in the UK and the US. They agreed. We did a first list of 10 books. One of these was The Empty Space, a translation of Geetanjali Shree’s novel Khali Jagah. Deborah read it, and she asked if Seagull would let Tilted Axis publish a paperback version of this novel since Seagull was publishing a hardcover version. I told her that I would ask Seagull but it seemed unlikely that they would want to give away paperback rights. It is a small market. Deborah said, “Okay, but what about Geetanjali’s new work?” This is the story of how Deborah and Tilted Axis got interested in Geetanjali’s work. I was having a separate conversation with Daisy, who was keen to translate writers in Hindi. I told her about Ret Samadhi when it was just out. I had read a bit of it, and was very excited though I read Hindi pretty slowly. I was thinking of how I would have translated the book myself if I was good at Hindi. Anyway, so, I told Daisy about Geetanjali’s novel, and I asked Geetanjali if she would be open to having it translated into English by Daisy. She said yes. There was an unfortunate tragedy in Geetanjali’s family, so things got held up for a while. I introduced Daisy and Geetanjali to each other. Daisy worked on a sample translation of a few chapters from the book. Geetanjali liked them, so Daisy sent them off to Deborah. Deborah liked what she read and wanted to publish the book. That’s how it all happened. I didn’t do anything extraordinary. When one is working in a particular field, one is always connecting people to each other. It’s not a big deal. Many others have done the same for me. While reading their book, did you think that it was destined for such glory? When I read the book, I had a feeling that it would get noticed in a big way but I was not really thinking of the International Booker Prize at that time. When the longlist was announced, I became 100 per cent sure that this book would win. When you have a book like this in the running, it doesn’t matter what the other books are. You know it is the right choice for the prize. I have been on juries before, so I had no doubt in my mind about the winner. You have translated Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay’s books from Bengali to English for Tilted Axis Press. How was the experience of working with them, especially as they identify themselves as “a non-profit press” publishing mainly Asian writers? Tilted Axis, which is based in the UK, is trying to challenge the kind of publishing structures that exist in Western markets at the moment. Deborah and her team commission translations of books written in languages that are typically not represented in Western markets. They are working with material that is seen as radical even in the languages of India. Chintan Girish Modi is a Mumbai-based journalist and book reviewer. Read all the **_Latest News_** _,_ **_Trending News_** _,_ **_Cricket News_** _,_ **_Bollywood News_** _,_ **_India News_** and **_Entertainment News_** here. Follow us on Facebook_,_ Twitter and Instagram_._

Arunava Sinha talks about translating a novel that critiques sexual violence and caste-based oppression, and the manuscript of a Bangladeshi poet in exile who received death threats for speaking up against persecution of Hindus.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)