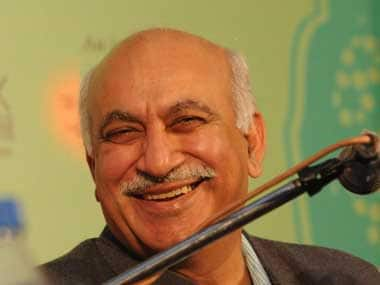

Journalist-turned-BJP politician MJ Akbar has already come under intense scrutiny over what he said after 2002 and what he is now saying about Narendra Modi. This is at it should be. When we change our views dramatically, it is absolutely appropriate that we should be questioned about what occasioned this change, and why now? In all the questioning and interrogation, Akbar acquitted himself creditably even though one may never know whether this change in stance comes from a genuine shift in opinion or was occasioned by the prospect of being close to the centre of power, now that Modi’s star seems to be in the ascendant. One of the realities all journalists and politicians have to accept these days is that they can never completely abandon their past. Just as Akbar had to explain why he changed his view, Ram Vilas Paswan had to explain why he joined hands with the same party he called the Bharat Jalao Party (BJP) some time ago. [caption id=“attachment_1449271” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Isn’t Akbar entitled to change his views? AFP[/caption] Take my case too. I have generally been favourably disposed to Modi’s rise over the last five years. But if after becoming PM one finds that that Modi is busy organising riots all over, do you think I won’t change my stand? The boot should thus be as much on the other foot too. What is unusual is not that one changes one’s stance as circumstances change – whether for personal profit or some other reason is not material here - but why one never wavers from a stand come what may. How is it reasonably possible that one can hold the same view about a person or a party never mind what change may have been brought about by circumstances or experience or scrutiny? If changing one’s stand calls for explanations, surely it is equally important for those who don’t ever change their views even when their arguments seem to be losing weight. If consistency is the virtue of fools, obstinacy in the face of changing reality is no virtue either. Akbar told his interrogators that Modi faced the most intense scrutiny from every organ of the state and society, and still they could not nail guilt to his door. “If, after 10 years of Congress scrutiny, there has been no linkage of Modi to Gujarat riots, we have to change our view.” Yesterday (24 March) Akbar wrote in an article in The Economic Times: “Every relevant instrument of state was assigned the task of finding something, anything, that could trace guilt to Modi. They could not. The Supreme Court, which is above politics and parties, and which is our invaluable, independent guardian of the law and Constitution, undertook its own enquiries. Its first findings are in, and we know that the answer is exoneration. One suspects that only some politicians have a vested interest in the past during an election when Indians want to vote for their future.” Akbar thus is indirectly asking: if no one could establish Modi’s guilt so far, why are his critics still holding on to their rigid views? Is not changing one’s views a virtue here? Of course, the answers could be the usual ones: the court process can go on indefinitely, from high court to Supreme Court and back and forth. If one charge does not stick, try another. While it is certainly true that the legal system cannot sometimes nail every guilty party, but surely the process has to stop somewhere? Sure, Muslims have every right to not believe in Modi. It may be upto the latter to woo them. But is it right to question the bonafides of those who do accept Modi at face value now? The problem ultimately boils downs to a simple human failing: human beings first decide whether they like or dislike somebody and then open or close their minds to him/her. If you like Modi, nothing he does will ever look bad to you. If you dislike him, he can stand on one leg and beg for fair judgment, but we will not listen. The problem is our beliefs determine what we accept as reason – and not the other way round. We believe that BJP is communal and so it can never change. We believe that some other parties are secular, and so even if there is evidence of their communal acts, we dismiss that as an aberration. We believe that if the BJP acts secular, that must be an aberration. There is no getting away from self-deception. I believe just as journalists and politicians who change their minds need to explain why, one needs to ask those who never change their minds why they refuse to do so. There is serious need for introspection here.

It is good that journalists and politicians who change their stands are queried why. But is it a great virtue if you never change your stand, come what may?

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by R Jagannathan

R Jagannathan is the Editor-in-Chief of Firstpost. see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)