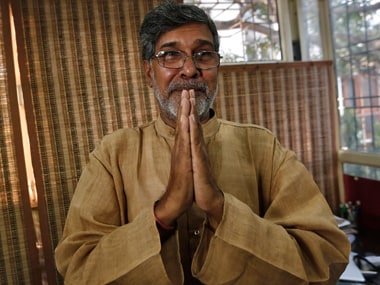

By Vivek Bhardwaj There are at least 30-odd emails from the Bachpan Bachao Andolan sent over the past three years lying in my inbox. Some of them are invitations to interact with Kailash Satyarthi, many to interact with kids rescued by his activists, and a few for press conferences on child labour. The emails were lying unread until yesterday because, instead of meeting Satyarthi, like most journalists, I would have preferred an off-the-record conversation with a politician or attending the launch of a new scheme by a local builder. [caption id=“attachment_1752157” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Child rights activist Kailash Satyarthi. Reuters[/caption] I make this confession to dispel the notion that we didn’t know about Satyarthi till his work was recognised in Oslo. Many of us, at least in the media, had heard of him; some of us had even met him on a few occasions. But most of us ignored him. Why? Because we did not identify with his cause. Many things in India do not shock us: dirty roads, stinking public toilets, men urinating in public places, a six-year-old taking orders at a road-side tea stall or an eight-year-old mopping our floors. These are part of Indian ‘culture’. Child labour– forced or voluntary– is not a priority for us. Chalta hai. Chhotu, ek cutting chai lana! When we see a ‘Chhotu’ working as domestic help, our first instinct is not to pity him. Many of us instead secretly pine for somebody similarly pliant and low-paid to serve us at home. Is it then a big surprise that we completely overlooked somebody who was trying to rescue these children? Thirty years ago, when Satyarthi broke away from Swami Agnivesh to work against child labour, he met with typical Indian resistance and justifications: What will a poor child do if not work? How will he eat? Do you want him to beg on the streets instead? Are we not helping him by letting him earn? Most sound both logical and valid considering the plight of our rural poor and their families. But Satyarthi’s comeback is more compelling: “A child who stays out of school and works as a labour is condemned to a life of poverty and slavery.” And yet nobody in India paid attention to his argument or his fight. “He won several international awards. But in India he was mostly treated as somebody who was making a lot of noise on a trivial issue,” one of his state co-ordinators said. He says that Satyarthi’s mission would have remained unrecognized had he not gone global. In 1992, Satyarthi led a Global March against Child Labour through 125 countries. If he had remained confined to India, Satyarthi would have remained every bit as invisible as the children he rescued. Satyarthi’s achievement is all the more impressive when viewed in the context of our the political and societal indifference toward child labour. In many ways, comparing him with Malala Yousafzai is unfair. Malala became an international icon within a few years because her campaign was met with brutal resistance from the Taliban. Satyarthi, ironically, was fighting against an equally powerful enemy, all the more mighty because there were no bullets to point to its brutality. Nobody resisted Satyarthi’s efforts; nobody issued a fatwa against him or threatened to put a bullet through his head. We attacked him instead with silence and apathy. “The Nobel Committee regards it as an important point for a Hindu and a Muslim, an Indian and a Pakistani, to join in a common struggle for education and against extremism,” the Norwegian committee said while announcing the award. This Nobel Prize has rightly reminded India and Pakistan of their common enemies. It has embarrassed us in front of the world by pointing out how we continue to mindlessly pound each other’s borders when there is so much we can all fight together. More importantly, it has also made us aware of the enemy within: our insensitivity towards social problems we sweep under the carpet, woven, perhaps, by a child.

Kailash Satyarthi’s Nobel Peace Prize award has made us aware of the enemy within: our insensitivity towards social problems we sweep under the carpet, woven, perhaps, by a child.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by FP Archives

see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)