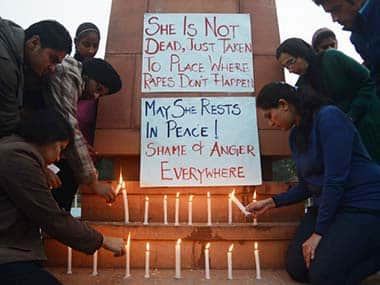

News about the possibility of a verdict on Thursday on the juvenile accused in the Delhi gang-rape case has revived the debate over the maximum term that a juvenile in conflict with law can be sentenced to. Under the Juvenile Justice Act, a juvenile offender can be kept in a special home for not more than three years – a provision that has been questioned in the context of the brutal gang-rape of a 23-year-old student and attack on her friend by six men inside a moving bus. One of the accused in the case is juvenile. Many have questioned the three-year term for being too light a sentence for such a brutal crime. The verdict on the juvenile, who has been charged by the Delhi Police of serious offences including gang-rape, murder, kidnapping and criminal conspiracy, was put off to July 25 after the defence submitted some clarifications to the Juvenile Justice Board on Thursday. A day earlier, on Wednesday, the Supreme Court reserved its judgement on eight petitions – filed by lawyers and individuals - challenging the constitutionality of the Juvenile Justice (JJ) Act, seeking tougher sentencing and dropping of the juvenile age from 18 to 16. The Centre defended the provisions of the JJ Act and its constitutional validity in the Supreme Court and child rights NGOs - Prayas and Haq Centre for Child Rights also argued in favour of the provisions of the Act. [caption id=“attachment_952195” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Protesters had sought a higher sentence for juveniles after the Delhi gangrape. AFP[/caption] Relating the background to the case, child rights lawyer Anant Kumar Asthana who represented Haq in the case said, “After the 16 December gang-rape, people were upset. Many people went to the Supreme Court to challenge the constitutional validity of Juvenile Justice Act saying that it was shielding criminals. Their argument was that JJ Act was unconstitutional and that it violates the right to life by shielding criminals. They argued that children who commit serious offences should be treated differently and maximum quantum of sentence should be raised.” Contesting the petitioners claims, Asthana argued, “Safety of society is one of the purposes of JJ Act and the problem of keeping society safe by keeping juvenile crime in control can be addressed by the effective implementation of the JJ Act, which unfortunately, is not happening.” On the question of the maximum term prescribed by the JJ Act, Prayas founder and former IPS officer Amod Kanth says, “The Supreme Court is fully cognisant of the entire juvenile justice process. First of all, the Juvenile Justice Act, 2000, does not provide for any kind of conviction or sentence.” “It provides for ‘dispositional alternatives’ and there are seven such alternatives and it includes community service, probational service, fine and care by trained persons. The last resort being that the juvenile is kept in a special home or safe place for a period of three years and not more, up to the time he turns 21,” he said. But what about in case of serious crimes, should there be a different yardstick for juveniles commit serious crimes? “Seriousness of the offence has been considered in JJ Act and there are special measures in the Act. Also, why consider only seriousness of offence? Why not also consider the seriousness of situation of the child?” Asthana said. Kanth says that legal provisions have taken into consideration all relevant circumstances, including gravity and nature of crime and antecedents of the juvenile concerned. “Our argument is that there are various provisions under the Criminal Procedure Code (Section 360, for example, which deals with order to release on probation on good conduct), and Young Offenders Act where young offenders are not supposed to be sent to jail. If you are not sending a young offender (an individual under 21 years of age), where is question of sending juvenile to jail?” says Kanth. On the rationale behind the three-year term, Asthana says, “The question of the three years not being sufficient came up prominently during the arguments. I argued that one should look at three years not as punishment but as time given to the government to reform a child." “If a child is addicted to drugs, has committed crime under the influence of drugs, it is necessary to de-addict him, give him vocational training so that that he doesn’t slip back into a life of crime. But our correction facilities are in a very bad shape. If after 16 December, the government is concerned about its people, it should improve its correctional facilities,” he said. Asthana argues that the best way to deal with crime is to implement the JJ Act effectively. “If you implement, you will see the result. But the government is not investing in it,” he said.

Many have questioned the three-year term for being too light a sentence for such a brutal crime.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)