So Wall Street Journal now has its very own WikiLeaks site. Dubbed the

WSJSafeHouse

that invites wannabe whistleblowers to submit “newsworthy contracts, correspondence, emails, financial records or databases from companies, government agencies or non-profits". In rarefied media circles, this counts as a victory for the Journal over its arch-rival New York Times, which has long been

promising

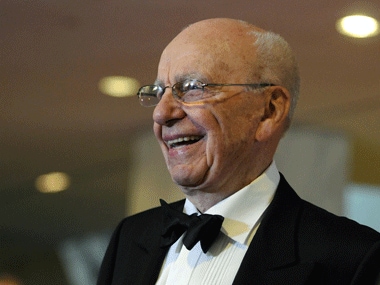

its very own WikiLeaks knockoff. [caption id=“attachment_4816” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“Media outlets are increasingly seen as conglomerates with business interests. And the Journal, owned by Rupert Murdoch, is on top of that game. Jonathan Ernst/Reuters”]

[/caption] WSJ is not the first out of the gate, of course. Al Jazeera announced the English version of its leak-collection site back in January. The Transparency Unit scored an early coup by landing a tranche of incendiary internal papers revealing hidden details of the Middle East process. Release of the so-called Palestine Papers prompted the New Yorker’s Raffi Khatchadourian to

ask

:

[/caption] WSJ is not the first out of the gate, of course. Al Jazeera announced the English version of its leak-collection site back in January. The Transparency Unit scored an early coup by landing a tranche of incendiary internal papers revealing hidden details of the Middle East process. Release of the so-called Palestine Papers prompted the New Yorker’s Raffi Khatchadourian to

ask

:

Has Al Jazeera taken the first step in a journalism arms race to begin acquiring mass document leaks?… In a future where in-house WikiLeaks portals are common to mainstream news organisations, is there a role for the original site? Will Julian Assange’s creation become a victim of its own success? And if his movement is taken over by established news organisations, how might it change?

All good questions to which Khatchadourian wisely offers few definitive answers. But the _Wall Street Journal’_s early experience suggests that it may not be as easy for traditional news organisations to inspire the same trust as an anarchic, stateless WikiLeaks. Yes, there are problems with its encryption technology – those can be fixed – but the greater challenge lies in the language designed to protect the newspaper’s own legal standing. The Journal is not an extra-judicial entity, operating in cyberspace outside national borders. It is subject to score of libel, slander, and national security laws that hamper its ability to ever guarantee true protection to its sources. Hence its alarming terms of use: “We reserve the right to disclose any information about you to law enforcement authorities or to a requesting third party, without notice, in order to comply with any applicable laws and/or requests under legal process." Even the Journal’s guarantees of anonymity are subject to the newspaper “remaining in compliance with all applicable laws.” US newspapers are loath to give up their sources, but they always have the freedom to do so. As the tech blog Betabeat wryly concludes , “It’s interesting to see a traditional journalistic outlet trying to adopt the strategy that worked so well for WikiLeaks. But so much of that site’s success was about reputation and trust. Debuting a service with a glut of legalese that makes it clear info will be flipped to authorities when an investigation goes down will not produce any Bradley Manning style leaks.” The other problem that journalists rarely mention is that media outlets are now increasingly seen not as brave watchdogs of democracy but vast media conglomerates with a range of business interests. The Journal is owned by the always controversial Rupert Murdoch, and the Times is just as much a media empire that includes 17 other daily newspapers and more than 50 Web sites. This may not directly affect the coverage but it does colour popular perception. If Al Jazeera remains an exception for now, perhaps because it operates in a part of the world where there are few other institutions dedicated to democracy, accountability, or free speech. A privilege not available to the rest of world where a Julian Assange often has far more anti-establishment credibility than an Arthur Sulzberger Jr. So it certainly doesn’t help when Assange himself makes it a point to broadcas t his skepticism:

[Newspaper] organisations could create such a site if they cared about it. But it’s our experience that at least the Guardian and New York Times don’t care so much to protect sources. In fact, for Cablegate the Guardian and the _New York Time_s communicated over phones. They swapped cables over email. The New York Times approached the White House with its list of stories it was going to publish on the cables one week before publication, and campaigned against the alleged source of the cables, Bradley Manning. We also cannot be sure that they would even publish the stories they receive. The New York Times sat on the story about the National Security Agency mass-tapping Americans for over a year. CBS sat on the story of the torture at Abu Ghraib for months.

Assange is hardly the first to voice such suspicions. When a newspaper refuses to publish a story or delays its publication today – be it New Delhi or New York – most are likely to suspect corporate self-interest than editorial restraint. “Deep throat” reporting requires absolute trust on the part of the vulnerable sources. That trust is hard to inspire in an era when big media is big business.

)