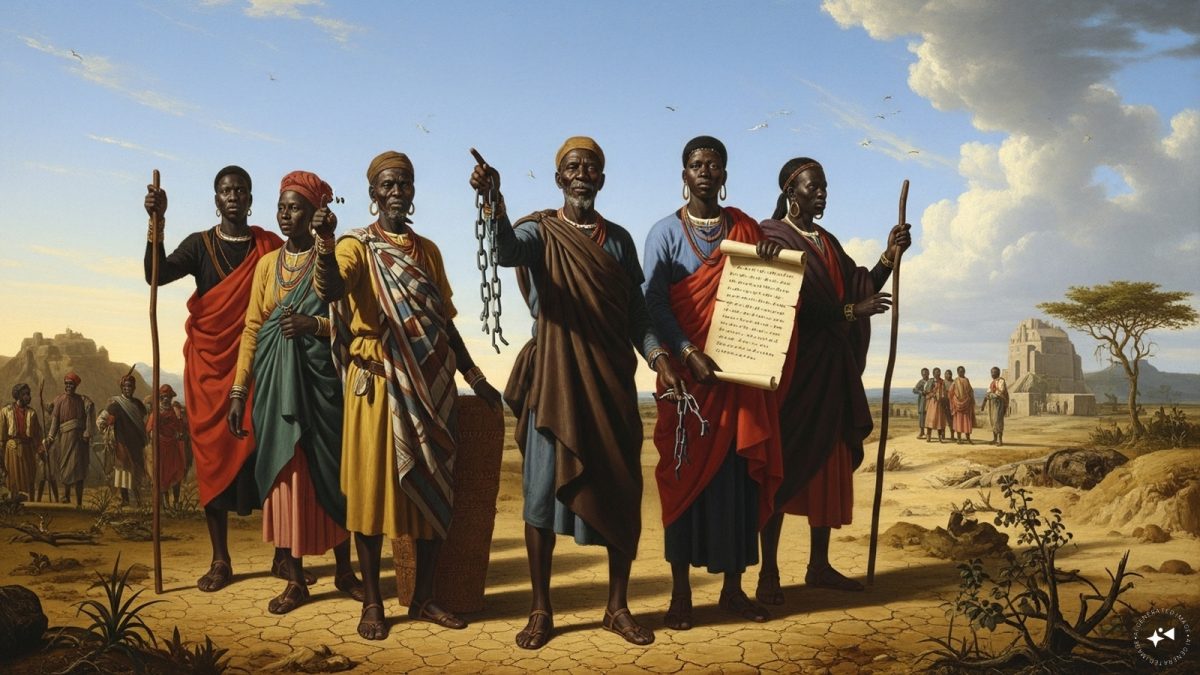

African leaders are intensifying efforts to ensure that crimes committed during colonial rule are formally recognised, criminalised, and addressed through meaningful reparations. Diplomats and senior officials gathered in Algiers on Sunday to advance an African Union resolution adopted earlier this year, seeking justice and compensation for communities harmed by centuries of exploitation, plunder, and violence.

Many participants emphasised that reparations must go beyond symbolic apologies, encompassing financial restitution, the return of looted artefacts, cancellation of colonial-era debts, and long-term development support. The debate has drawn parallels with Asia, where estimates suggest India alone may have lost resources worth trillions of dollars in today’s value, highlighting the scale of extraction that former colonies argue must be acknowledged and addressed.

Algeria’s history as a reminder

Opening the conference, Algerian Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf said Algeria’s history under French occupation underscored the urgency of restitution and the recovery of stolen property. He added that a dedicated legal framework would ensure that reparations are treated as “neither a gift nor a favour.”

“Africa is entitled to demand the official and explicit recognition of the crimes committed against its peoples during the colonial period, an indispensable first step toward addressing the consequences of that era, for which African countries and peoples continue to pay a heavy price in terms of exclusion, marginalisation and backwardness,” Attaf said.

While international conventions prohibit slavery, torture, and apartheid, colonialism itself has never been explicitly outlawed. This gap was a key focus at the African Union’s February summit, where leaders discussed forming a unified stance on reparations and defining colonisation as a crime against humanity.

The economic and cultural toll

The economic impact of colonialism on Africa is estimated to be staggering. European powers extracted natural resources through coercion, profiting from gold, diamonds, rubber, and other commodities, while leaving local populations impoverished. Calls for the return of looted African artefacts held in European museums have intensified in recent years.

Attaf emphasised the significance of holding the conference in Algeria, describing the country’s experience under French rule as among the harshest examples of colonial oppression. Nearly a million European settlers enjoyed superior rights, even as Algerians were conscripted to fight in World War II. During the independence struggle, hundreds of thousands were killed, and French forces employed torture, forced disappearances, and village destruction as part of counterinsurgency campaigns.

“Our continent retains the example of Algeria’s bitter ordeal as a rare model, almost without equivalent in history, in its nature, its logic and its practices,” Attaf said.

Quick Reads

View AllLinking history to modern conflicts

Attaf also drew parallels with the Western Sahara dispute, framing it as a case of incomplete decolonisation. Echoing the African Union’s stance, he called it “Africa’s last colony” and praised the Sahrawi people’s fight “to assert their legitimate and legal right to self-determination, as confirmed — and continuously reaffirmed — by international legality and UN doctrine on decolonisation.”

Algeria has long pressed for colonialism to be addressed under international law while avoiding political tensions with France. French President Emmanuel Macron, in 2017, acknowledged aspects of the history as a crime against humanity but stopped short of a formal apology, urging Algerians not to dwell on past grievances.

Mohamed Arezki Ferrad, a member of Algeria’s parliament, told the Associated Press that reparations must go beyond symbolism, noting that key Algerian artefacts seized during colonial rule, including the 16th-century cannon Baba Merzoug, remain in France.

The UK-India reparations debate

In India, the case for formal reparations from the United Kingdom has gained renewed attention, particularly following Germany’s reparations to Namibia. In May 2021, Germany agreed to pay €1.1 billion over 39 years to the Herero and Nama people of present-day Namibia for a genocide committed between 1904 and 1908. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas described this as “the darkest period in our shared history,” emphasising Germany’s moral and historical responsibility and ensuring the funds support reconstruction and development.

Germany’s approach contrasts sharply with that of other European powers, many of whom maintained colonial empires without offering formal apologies or meaningful compensation.

Three pillars of the case for UK reparations

Proponents argue that the UK owes India reparations based on three key factors:

Economic exploitation: The British systematically de-industrialised India, extracting resources and using the country as a captive market for British goods. India, which contributed over 20% of global trade before colonial rule, was left impoverished by the time of independence in 1947.

Violence and oppression: British policies caused famines, massacres, and widespread suffering. Notable examples include the Bengal Famine of 1943, which killed over 2.5 million, and the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh Massacre.

Division and communal strife: British “Divide and Rule” strategies fostered communal tensions, culminating in the Partition of 1947 and creating enduring social and political fractures.

The cumulative effect was economic devastation and social fragmentation, alongside the enrichment of Britain. This forms the basis for India’s moral and material claim for reparations.

Shashi Tharoor and the moral argument

Congress parliamentarian Shashi Tharoor has been a prominent advocate, arguing that even nominal reparations, such as £1 annually, would symbolically acknowledge Britain’s responsibility. Tharoor emphasises that the gesture of taking responsibility matters more than the sum itself.

Germany’s example as a benchmark

Germany’s approach to Namibian reparations shows that former colonisers can go beyond symbolic apologies, providing substantive support for the economic, social, and cultural development of affected nations. Applied to India, this principle suggests that the UK should not stop at a token apology but must acknowledge its ongoing obligation to materially contribute to India’s development.

While calculating the exact sum is challenging, the principle of reparations remains valid. Foreign aid from the UK to India should be considered part of this obligation rather than a benevolent gesture. Germany’s example sets a benchmark for meaningful reconciliation, demonstrating that accountability for historical crimes can and should extend into practical support for development.

)