By Pratik Karki Seventh in a series of historical documents, the present Constitution of Nepal promulgated on 20 September, 2015 with almost 90 percent approval is the first Constitution in the history of this nation to have been drafted and promulgated by a democratically elected Constituent Assembly. Yet, over 100 days later, the Constitution continues to be met with a series of protests, especially in the Terai/Madhesh region of Nepal, where it is labelled discriminatory. There have been over fifty

deaths, mostly that of protestors but also

policemen and a huge polarisation within the country. There has also been a

border blockade at the Nepal-India border, which has resulted in serious difficulties in a country that is yet to recover from the devastating April earthquake. For a country with deep historical and people-based ties with India, the official Indian statement rather than welcoming the Constitution, tersely

stated “We note the promulgation in Nepal today of a Constitution_”_ Instead, India has been seen as taking sides in a complex dispute and the term “unofficial blockade” attributed to India by a considerable section of Nepali citizens and the Nepali

establishment as well. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs continues to stress on the need for consensus despite the understanding that democratically written Constitutions in divided societies are essentially documents of the best possible compromise. This article presents the primary demands of the protesting United Democratic Madheshi Front (UDMF), and analyses the contentious provisions of the Constitution of Nepal along with the Constitutional Amendment Bill that is currently in the

second stage of deliberations in Nepalese Legislative-Parliament. [caption id=“attachment_2546712” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] Nepal’s Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli. AFP[/caption] The 11-point

demands of the currently agitating UDMF primarily revolve around:

- Definition of Nepal as a multi-national State rather than a monolithic national State

- Execution of multilingual policies in all federal, provincial and local bodies.

- Clear provision regarding marital citizenship in the Constitution and not in federal law.

- Guarantee of the principle of ‘Proportional Inclusion’ in all State organs at all levels.

- Population as the primary criteria for constituencies for the lower House, ie House of Representatives, as well as representation in the Upper House, i..National Assembly on the basis of population.

- Demands for a Federal demarcation with two autonomous provinces in the Terai/Madhesh region.

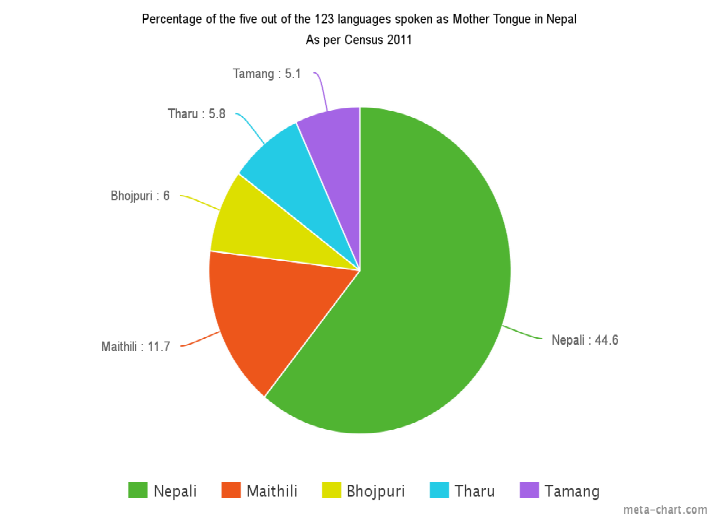

Defining Nepal The definition of the nation and the State of Nepal can be found in Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution. Article 2 defines the nation to be “ All the Nepalese people, with multiethnic, multilingual, multi-religious, multicultural characteristics and in geographical diversities, and having common aspirations and being united by a bond of allegiance to national independence, territorial integrity, national interest and prosperity of Nepal, collectively constitute the nation” whereas Article 3 (1) defines the State of Nepal to be an “independent, indivisible, sovereign, secular, inclusive, democratic, socialism-oriented, federal democratic republican State”. It is clear from a literal reading of these provisions that the definition of the nation is neither monolithic nor prioritising of any one ethnicity, language, culture or religion but instead attempts to celebrate the multiple differences inherent in the citizens of Nepal. Given that the federal structure of Nepal is an evolution from an essentially unitary State and not from the coming together of two or more nations, it is unlikely that the definition of Nepal will be changed to include a multi-national character. The language issue The current Constitutional provisions regarding language are enumerated in Article 6 and Article 7 of the Constitution. Article 6 provides that “All languages spoken as the mother tongues in Nepal are the languages of the nation” whereas Article 7 (1) declares Nepali to be the official language in Nepal. However, Article 7 (2) provides space for a multi-lingual policy in the provinces in the Terai/Madhesh region by stating “A State may, by a State law, determine one or more than one languages of the nation spoken by a majority of people within the State as its official language(s), in addition to the Nepali language” Further Article 7 (3) allows for other issues related to language to be decided by the Government of Nepal on the recommendation of the Language Commission, which shall, as per Article 287, be constituted with a representation of the States within one year of the commencement of the Constitution. The latest Nepal Census of

2011 lists 123 languages as being spoken as mother tongues in Nepal.

As the chart shows, Nepali is the mother tongue of almost half of the overall population of Nepal, and is mostly understood throughout the country, including the overall Terai/Madhesh region where it is the

single largest language spoken as a mother tongue (3.5 million Nepali speakers compared to 3 million Maithili speakers). While the use of a neutral language such as English can be academically mooted, it is impractical and not the demand of the protestors. It is clear that the State cannot practically implement a multilingual policy for all of the different languages spoken in the country. However, the Constitution has left enough scope for multilingual States, and the same is possible in the States that have been carved out in the Terai/Madhesh region under the current Constitution. Citizenship Citizenship has always been a contested arena in Nepali politics, given the open border between Nepal and India and lax record keeping on both sides of the international border, giving rise to allegations of people holding dual nationalities. However, as widely and inaccurately reported in some sections of the Indian media, the Constitution of Nepal does not discriminate against its citizens on the basis of ethnicity. The Constitution does however have

gender discriminatory provisions, but those have not been the targets of protests from the UDMF. The Constitution also continues with the previous categories of descent, naturalization and honorary citizenship and a new category of non-resident Nepalese citizenship with socio-cultural and economic rights. Further, through Article 289 (1) it seeks to limit certain top executive and constitutional posts such as the President, Vice-President, Prime Minister, Chief Justice, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Chief of State, Chief Minister, Speaker of a State Assembly and chief of a security body to citizens by descent. However, even this Article is not the focus of sustained protests by the UDMF, given that most of the Madheshi citizens in Nepal are citizens by descent. Article 11 (6) of the Constitution of Nepal provides that,” A foreign woman who has a matrimonial relationship with a citizen of Nepal may, if she so wishes, acquire the naturalised citizenship of Nepal as provided for in the Federal law” [caption id=“attachment_2442030” align=“alignright” width=“380”] File image of protests in Nepal. AP[/caption] The criticism of the UDMF is that the phrase (as provided for in the federal law) makes the status of Indian women married to Nepali men (mostly from the Madheshi community) subject to a constitutional flux, and hence would probably make their children unable to receive citizenship by descent. However that is not true and foreign women married to Nepali citizens have been continuing to receive naturalised citizenships even post the promulgation of the current Constitution of Nepal, as per the provisions of the existing

Citizenship Act, 2006. Nevertheless, this is an arena where there is consensus among all the major political parties, and the impugned provision should either be removed through a constitutional amendment or a statement clarifying the provision should be issued by the government as well as the major political parties. Guarantee of ‘proportional inclusion’ at all levels The Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007 created a basis for an inclusive State. As a result of this the concept of affirmative action was introduced in Nepal. Thus forty five percent of government jobs are now reserved for different categories such as women, indigenous nationalities, Madheshis, Dalits, people with disabilities and people from backward region. In addition, Article 18 (3) dealing with the Right to Equality allows for the making of special provisions by law for the protection, empowerment or development of a wide range of classification. This classification can be further seen in Article 42 (1) dealing with the Right to Social Justice which provides that “The socially backward women, Dalit_, indigenous people, indigenous nationalities,_ Madheshi_,_ Tharu_, minorities, persons with disabilities, marginalised_ communities_, Muslims, backward classes, gender and sexual minorities, youths, farmers, labourers, oppressed or citizens of backward regions and indigent_ Khas Arya shall have the right to participate in the State bodies on the basis of inclusive principle” The fact that Article 42 (1) uses the term ‘inclusive principle’ rather than ‘proportional inclusive’ has seen protests from the UDMF who fear that this will be used to sideline Madheshis and other groups from their rightful participatory share in all organs of the State. The fear however, is not based on a sound constitutional footing. The current Constitution of Nepal clearly accepts the principle of proportional inclusion. The term ‘proportional inclusive’ is used in the Preamble as the basis for an egalitarian society and is further used in Article 38 (4) and Article 40 (1) guaranteeing women and Dalits respectively the right to participate in all bodies of the State on the basis of the principle of proportional inclusion. It is also used in Article 50 as part of the Directive Principles of the State. Similarly, Article 285 (2) regarding the constitution of government service states that positions in the federal civil service as well as all federal government services shall be filled through competitive examinations, on the basis of open and proportional inclusive principle. With the discussion of the Constitutional Amendment Bill in the Nepalese Legislative Parliament the term “on the principle of inclusion” in Article 42 (1) looks set to be replaced with the term “on the principle of participatory inclusion” and this demand has been fulfilled. However, it is necessary to add that the concept of ‘proportional inclusion’ has yet to be properly clarified and problems are bound to crop up regarding the implementation of these provisions. Population as the primary criteria for constituencies The Constitution of Nepal provides for a 275 member House of Representatives with 165 directly elected and 110 proportionally elected members. Article 84 (1) (a) provides for the delimitation of constituencies based on ‘geography and population’. This has been contentious, as the UDMF have been arguing that this discriminates against the Terai/Madhesh regions where 51 percent of the total population of Nepal resides. The language to the Constitutional Amendment Bill accepts this argument and the primacy of population has been recognised through the proposed amendment to Article 84 (1) (a) with the delimitation of constituencies now being “on the basis of population and geographical necessity and specialisation”. Further the proposed amendments to Article 286 (5) and 286 (6), cement the primacy of population while also guaranteeing that sparsely populated mountainous districts with huge natural resources are not left unrepresented. The representation to the National Assembly, as per Article 86 is based on the equality of the federal units and not on the basis of population and thus following the American and South African model of second chambers, rather than the Indian model. This ensures that the interests of the States that have a much larger population do not overwhelm the interests of smaller States. Of course, there is no right or wrong model, simply different constitutional designs, but with the possible amendment to the relevant provisions of the Lower House, it is likely that equal representation for the different federal units rather than the primacy of population shall continue at the National Assembly. Demands for a federal demarcation with two autonomous provinces This is the most contentious issue and one that has continuously been put forward as the bottom-line of the UDMF, and is the reason of their continued objection to the Constitutional Amendment Bill as it is silent on the seven State model. Article 56 (3) of the Constitution regarding the federal structure states that “There shall be States consisting of the Districts as mentioned in Schedule-4 existing in Nepal at the time of commencement of this Constitution”. The twenty districts of the Terai/Madhesh region (out of a total of seventy five districts in Nepal) are divided within the seven States as following:

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)