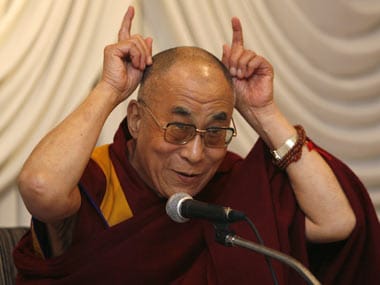

In moments of child-like candour, during his interactions with his followers, the Dalai Lama occasionally likes to play the devil. Noting that the Chinese media and Chinese leaders frequently demonise him, even calling him a “wolf in monk’s robes” and “a devil”, he would playfully put up his fingers to give himself mock horns, and say: “See, don’t I look like the devil with horns?” Such impish interactions, which endear the Dalai Lama to his followers just as much as the force of of his spiritual leadership of the Tibetan Buddhist order, hide the formidable soft power that the 76-year-old old monk wields – and which China, for all its hard power projection around the world, struggles unsuccessfully to match. [caption id=“attachment_141174” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“What is it about this 76-year-old giggly monk that has China breathing fire? Reuters”]

[/caption] The latest manifestation of Chinese leaders’ paranoia of power has claimed an unlikely victim. The latest round of talks between India and China on their contentious border dispute, scheduled to begin in New Delhi on Monday, have been indefinitely postponed after China demanded that a Buddhist conference in Delhi, which the Dalai Lama is to address, be cancelled.

The conference, which begins today

, is being organised by the Asoka Mission, a transnational Buddhist sangha, but is believed to enjoy the unofficial patronage of the Indian government and of Indian officials. That the conference dates, arranged months ago, coincided with the dates for the Sino-Indian border talks must count as something of a scheduling snafu; but what really rankled with the Chinese authorities was the prospect of the Dalai Lama addressing the Buddhist conference on the same day that the Chinese special representative Dai Bingguo would be in Delhi.

Some media reports claim

that the Chinese officials were rather more disquieted by the fact that the Asoka Mission had invited Buddhist delegates from China to the conference and to share the platform with the Dalai Lama. At their instance, the Indian external affairs ministry clarified that no Indian leader – not the president, not the prime minister – would attend the conference, which in any case was a private affair. And even the Dalai Lama’s attendance at the conference was to be delayed until after the Sino-Indian talks were completed. Yet, the Chinese side evidently raised the stakes even further, and demanded that the conference, which had been planned months in advance and involved extensive logistical arrangements with Buddhist clergy from several countries, be cancelled in its entirety. Indian officials, who had gone the extra mile to accommodate Chinese officials’ hypersensitivity to the Dalai Lama’s concurrent presence in Delhi, declined, prompting China to call off the talks at the last minute. China’s disproportionate response to the Dalai Lama’s influence,

as we’ve noted earlier

, borders on excessive paranoia. China’s manner of dealing with governments whose leaders meet the Dalai Lama may appear to showcase its hard power projection, but is increasingly being seen as petulant overreaction. China even invokes its commercial clout too to “punish” countries that receive the Dalai Lama. And as the latest episode, involving the indefinite postponement of the Sino-Indian border talks, show, it’s a strategy that will very likely yield diminishing returns. The trouble with playing a trump card too often and at the slightest provocation is that it ceases to be a trump card. The fact that even an extremely accommodating Indian officialdom, which has traditionally been exceedingly wary of Chinese hectoring, has in recent times found a bit of spine shows up the limits of China’s hard power projection.

A recent over-the-top commentary

in the official Chinese media claimed that India’s “inferiority complex” underlay India’s excessive worries about Chinese engagement in South Asia and its fears of an “encirclement”. China’s own foot-stomping response to the Dalai Lama shows up its frustrations when the irresistible force of its hard power meets with the immovable object of a giggly monk.

[/caption] The latest manifestation of Chinese leaders’ paranoia of power has claimed an unlikely victim. The latest round of talks between India and China on their contentious border dispute, scheduled to begin in New Delhi on Monday, have been indefinitely postponed after China demanded that a Buddhist conference in Delhi, which the Dalai Lama is to address, be cancelled.

The conference, which begins today

, is being organised by the Asoka Mission, a transnational Buddhist sangha, but is believed to enjoy the unofficial patronage of the Indian government and of Indian officials. That the conference dates, arranged months ago, coincided with the dates for the Sino-Indian border talks must count as something of a scheduling snafu; but what really rankled with the Chinese authorities was the prospect of the Dalai Lama addressing the Buddhist conference on the same day that the Chinese special representative Dai Bingguo would be in Delhi.

Some media reports claim

that the Chinese officials were rather more disquieted by the fact that the Asoka Mission had invited Buddhist delegates from China to the conference and to share the platform with the Dalai Lama. At their instance, the Indian external affairs ministry clarified that no Indian leader – not the president, not the prime minister – would attend the conference, which in any case was a private affair. And even the Dalai Lama’s attendance at the conference was to be delayed until after the Sino-Indian talks were completed. Yet, the Chinese side evidently raised the stakes even further, and demanded that the conference, which had been planned months in advance and involved extensive logistical arrangements with Buddhist clergy from several countries, be cancelled in its entirety. Indian officials, who had gone the extra mile to accommodate Chinese officials’ hypersensitivity to the Dalai Lama’s concurrent presence in Delhi, declined, prompting China to call off the talks at the last minute. China’s disproportionate response to the Dalai Lama’s influence,

as we’ve noted earlier

, borders on excessive paranoia. China’s manner of dealing with governments whose leaders meet the Dalai Lama may appear to showcase its hard power projection, but is increasingly being seen as petulant overreaction. China even invokes its commercial clout too to “punish” countries that receive the Dalai Lama. And as the latest episode, involving the indefinite postponement of the Sino-Indian border talks, show, it’s a strategy that will very likely yield diminishing returns. The trouble with playing a trump card too often and at the slightest provocation is that it ceases to be a trump card. The fact that even an extremely accommodating Indian officialdom, which has traditionally been exceedingly wary of Chinese hectoring, has in recent times found a bit of spine shows up the limits of China’s hard power projection.

A recent over-the-top commentary

in the official Chinese media claimed that India’s “inferiority complex” underlay India’s excessive worries about Chinese engagement in South Asia and its fears of an “encirclement”. China’s own foot-stomping response to the Dalai Lama shows up its frustrations when the irresistible force of its hard power meets with the immovable object of a giggly monk.

Venky Vembu attained his first Fifteen Minutes of Fame in 1984, on the threshold of his career, when paparazzi pictures of him with Maneka Gandhi were splashed in the world media under the mischievous tag ‘International Affairs’. But that’s a story he’s saving up for his memoirs… Over 25 years, Venky worked in The Indian Express, Frontline newsmagazine, Outlook Money and DNA, before joining FirstPost ahead of its launch. Additionally, he has been published, at various times, in, among other publications, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, Outlook, and Outlook Traveller.

)