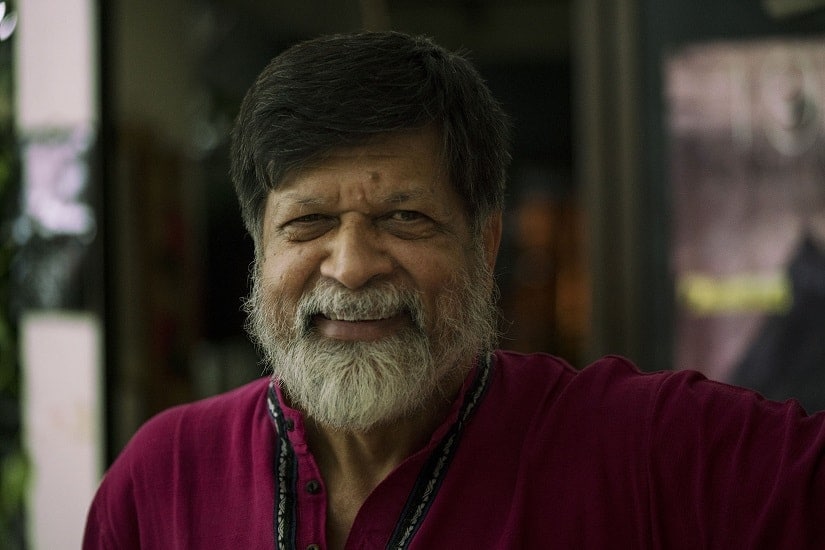

Shahidul Alam, one of the most prominent faces in South Asian photography, was picked up from his house in August, hours after his scathing interview with Al Jazeera about student protests for safer roads. Unsettled by the intense global outrage that followed, the authorities in Bangladesh have recently permitted his release . In this exclusive, wide-ranging interview, he talks about his incarceration, freedom of expression, journalism, activism, politics, custodial torture and his plans to work on prison reform. Amnesty termed you “a prisoner of conscience,” meaning you were detained simply for peacefully expressing your views. There are many who have suffered the same fate as you, for the same reason. Why do you think the government finds voices like you so threatening? As the American journalist IF Stone points out, “All governments lie”. Though levels vary, I do not know of any government that does not promote freedom in its rhetoric but oppose it in its practice. This is particularly true of authoritarian regimes as they as they are fearful of free thinking and intolerant of dissent. While governments use fear as a means to curb dissent, they tend to forget that both fear and courage are contagious. What I voiced was not a secret. I provided no information that was not common knowledge, but given my track record as a campaigner for social justice, and that I am critical of political parties wedded to status quo politics, my voice and that of others in my situation, has greater credibility. At the least, my statement proved that it could be said, in public and in international media. This is what scares governments. Beneath the veneer of propaganda, the truth is dying to escape. The lid being opened provides the space for all other dissenting voices to emerge. Governments are scared the dam might burst and their carefully managed veneer might disintegrate, exposing the truth. [caption id=“attachment_5684061” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Shahidul Alam. Photo courtesy Rahnuma Ahmed[/caption] During your imprisonment, your case triggered worldwide concern over the state of freedom of speech in Bangladesh. Now that you are a free man again, how do you plan to use your heightened stature as a free speech warrior to shed light on Bangladesh’s dismal record on human rights? I am not a free man. I am out on bail, but the charges against me remain and I potentially face seven to 14 years in prison. More significantly, my arrest clearly took place in an environment where I was not free. There has been no change in this environment. The same repressive laws, the same institutions and the same structure of governance are in place, so where is this freedom?

Freedom of thought and speech is under threat all across the globe, but now that we have demonstrated the power of collective resistance, they know that we are not alone.

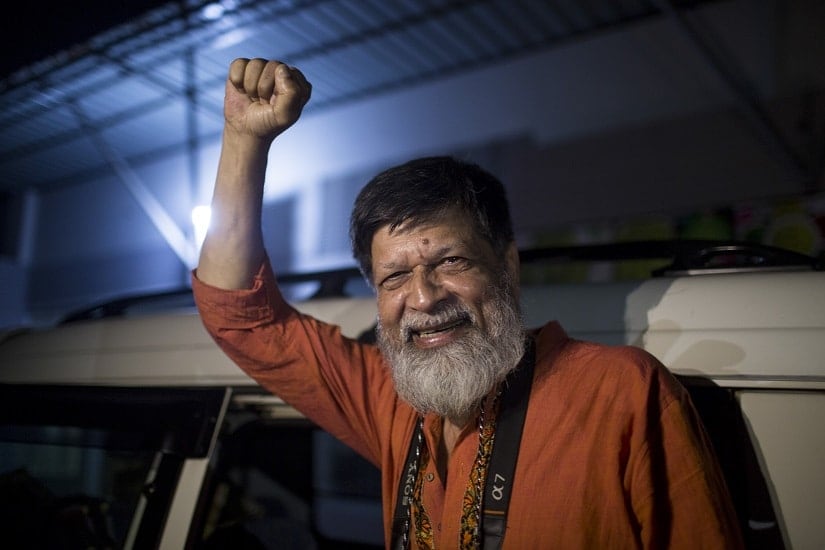

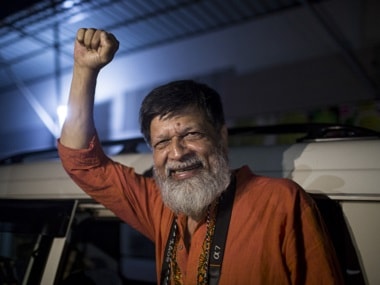

The global campaign and the increased scrutiny means that human rights abuses cannot as easily be swept under the carpet. The government has suggested that ‘development’ justifies loss of rights. Slick PR, sycophant intellectuals and academics, and a subservient media and state machinery have tried to project the myth of a contented public. The myth has been torn asunder. It is now my job and that of the many others who walked the walk, in Bangladesh and across the globe, to ensure that the lid cannot be shut again. There can be no going back. Our government and corporate interests revel in the unfettered opportunities for trade that globalisation has created; they forget that it also enables global resistance. While nation states bicker amongst themselves in South Asia, the solidarity shown by activists, artists, writers, journalists and general citizens across South Asia and around the globe, is evidence that we don’t buy the divisive arguments status quo politicians use. We come together when it matters. It is also important to point out that press censorship and the suppression of truth is not a problem of the Majority World alone. Julian Assange and Edward Snowden continue to be persecuted for demanding digital freedom. Organisations like The Tricontinental Institute for Social Research continue to campaign for the original goals of a struggle for peace and disarmament that the Non Aligned Movement had championed. The judiciary in India, Pakistan and Nepal have taken bold stances despite the dominance of militaristic or communal forces. We are no longer a push-over and will continue to resist. While it’s clear that you were detained for your scathing interview with Al Jazeera, authorities officially objected to your Facebook Live videos during the student protest for safer roads. That was probably because there was no law to prosecute speech made to the press. Therefore, the authorities had to use the ICT Act, the notorious internet law. There are now two laws — the Digital Security Act and Broadcast Act — that threaten the press more directly. The latter penalises anyone presenting “false or misleading information” on TV shows. Do you think your case somehow could have served as the trigger for enacting these laws? Good journalism is always investigative. In the process you often unearth facts that go against the interests of the powerful. If news is defined as something that someone somewhere wants to suppress, then gathering and reporting news will always upset someone or go against someone’s interest. If that becomes illegal, then journalism is illegal. That is precisely what these laws are designed to do, turn media houses into PR establishments. The Digital Security Act has been on the table for quite some time, and I am sure the Broadcast Policy was also in the mind of the government, though it is true that it was hurriedly implemented. While Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury, I, and others who have spoken out recently are definitely seen as a threat, the timing I believe, has to do with the upcoming elections. The government is getting increasingly desperate as the election looms. Clearly a repeat of the uncontested election of 2014 is not something they can get away with. So the upcoming elections have to be ‘managed’. Repressive laws and a complicit media — some private TV channels are more effective in manufacturing propaganda than even the state-owned BTV — and the coterie of lapdog intellectuals that surround the government are part of that ‘management’ mechanism. [caption id=“attachment_5679041” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Shahidul Alam on the day of his release from prison. Photo courtesy Sumon Paul[/caption] Interestingly, while governments generally reject what previous governments have done, in the case of repressive laws, each government has wholeheartedly embraced the laws enacted by previous governments, and generally reinforced them. Both RAB, or the Rapid Action Battalion, infamous for extra-judicial killings that was formed in 2004, and the Information and Communication Technology Act of 2006, were introduced by the BNP government. The Special Powers Act was enacted by the Awami League regime in 1974. The opposition of the time had protested against these laws, but never repealed them when they themselves came into power. The new laws sadly are mere extensions of this process. I am certain, if there is a change of government, while the new regime might backtrack on other things this government has done, the repressive laws will remain intact. As Left leader Zonayed Saki points out —

Unless and until we are able to dismantle the ‘structural authoritarianism’ that has outlived the breakup of Pakistan, that has continued and prospered in independent Bangladesh, the citizens of this land will never be really free.

In a recent post on Facebook, you said you’ll spend more time on prison reforms from now on. Certainly, Bangladesh’s prison cells are infamous, but which aspect of your imprisonment prompted you to take this decision? And how do you plan to do that? While I had been trying to work on our jail system for some time, I can’t really say I knew very much about it. Being there for over 100 days gave me an insight I might otherwise never have had. I came across many people who have been imprisoned on false charges, many who have no access to legal help (the para-legal help provided has severe limitations). There are many opportunities for reform. Inspired by other prisoners who initiated adult education classes, along with some others, I thought of starting a vegetable garden, setting up a musical band, and numerous other initiatives. With the help of my family and friends outside who were very generous with their support, I did what I could to help, but realised that it will not be possible without the support of the authorities. We shall have to work from within the system, finding ways to change the culture. With a changed mindset, I think a more radical shift is possible. The need for decent medical facilities, access to open university are things that I might be able to help with now that I am outside, but a very large number of prisoners shouldn’t be there in the first place, and I would like to work with human rights organisations to get them released. I am now trying to arrange jail visits whereby I can continue to visit the inmates. I now have many friends inside, at all levels, and I hope to utilise this access and this trust to full effect. I also want to revisit the sparrows that I used to feed from my cell every day! Immediately after your release, you have been admitted to a hospital to address what one of your colleagues told me were “torture-related complications.” Moreover, shortly after your detainment, while you were being taken to the court, you alleged that you were tortured so badly that your blood-stained panjabi (tunic) had to be re-washed. Torture in police custody has been a well-documented and disturbing phenomenon in Bangladesh. Can you tell us a bit more about how you were treated while in custody? Having heard other prisoners tell me how they suffered at the hands of law-enforcing agencies, I believe the torture I faced was relatively minor. I had trouble eating for the first two-and-a-half months because of the pain in my gums, but that pain has largely receded, it recurs with less frequency now. I had vertigo for some time, which I’ve also largely recovered from. The psychological trauma is something that might take more time, though I no longer hallucinate. The humiliation is something that will live with me forever. I would break it down into three phases. The first was on the night I was forcibly abducted. I did resist, and some of the injuries I obtained resulted (from) them forcing me out of the house, shoving me into the lift and later into the microbus (I resisted at each step). I had some injuries, but I don’t think these were a result of them deliberately trying to injure me, but caused by the force used to subdue me. I was handcuffed behind my back and received some cuts due to the handcuffs rubbing constantly against my wrists. This too was minor. I was screaming all the while and when someone tried to gag my mouth, I bit him. They didn’t try to gag me after that, but did blindfold me. [caption id=“attachment_5679061” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Students shout slogan during a rally as they join in a protest over recent traffic accidents that killed a boy and a girl, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, this August. REUTERS[/caption] They were furious with me as they could not get me to ‘confess’ to their allegations. That’s when they hit me in the face and I began bleeding from my mouth. This resulted in the pain in my mouth that I had for the next few months. A problem which continues. I will admit that I was scared when they said they would abduct my partner and asked for the ‘pins’ and started describing their waterboarding methods. The weight placed on my head was, I suspect, merely an attempt to disorient me, as was making me walk up and down the stairs and going round in circles, all blindfolded. They did repeatedly mention that the treatment I was getting was mild compared to what awaited me. My worst fear was when my blindfold was removed and I found myself facing a large pond. I was still handcuffed, and while I am a powerful swimmer, I clearly had no chance to survive if shoved into the water. After letting me stand there for some time, they put on the blindfold again and walked me to an office, where I slept on the floor in between two desks. The fact that I had to leave the toilet door open and that there was no contact with the outside world upset me more than the physical discomfort. The ride to the Keraniganj prison in the prison van was uncomfortable, but not really painful. The other prisoners all recognised me and were very helpful. Someone gave me a banana and some bread. Another offered water. We were all handcuffed. They repeatedly told me how proud of me they were and how they supported my actions. This continued inside the jail and many people came up to me to say how they had all prayed for me. This was a great source of comfort. Even within the prison, people recognised me and were respectful towards me. I was spared the indignity of ‘Amdani’, the ward where prisoners are ‘sold’. They sent me to Surjamukhi, where again, prisoners came forward to take care of me. I was put in a cell with a convicted murderer who found me a piece of cloth which I could use as a pillow and gave me water to drink. It was after ‘lockup’ so no jail food was on offer. We shared the bread and banana. They told me I needed to go to the case table the next morning at 5 am. I was required to crouch on the floor along with the other prisoners, which I found painful because of my injuries, so I knelt. One of the wardens objected, but others intervened. The officer logging in prisoners also recognised me and gave me a chair to sit on. Once I went back to my cell, many prisoners came to see me and asked if they could help in anyway. They gave me water and biscuits and we shared lunch. They also lobbied the warden, so two days later, I was put in a cell of my own. However, this cell was close to the staircase, and very dusty. Since I slept on the floor, I developed an allergy, probably due to the dust. This led to serious breathing problems. Meanwhile my lawyer had written to the prison authorities and my family had publicly appealed to the jail authorities to provide me with urgent medical care, so I was then taken to the prison hospital. At the hospital, I told the doctor of my problems and because of the appeal I was eventually taken to an external hospital where they did some tests. They didn’t look into the pain in my mouth which was my major problem. I came back to the prison hospital and later met the prison dentist, who gave me medicine, but warned that the pain would probably stay for another three weeks. When I went back to him after three weeks as I still had the pain and could not eat solids, he looked again and said, I would probably experience pain for a few more months but it would go away. He told me to gargle with warm salt water several times a day. It worked and after two-and-a-half months, the pain largely subsided. I was later shifted to ‘division’, which are facilities for VIP prisoners. The food there was better, I had a rather large room to myself and a bed to sleep in. I was also allowed an ‘office call’ once a week where my family could sit beside me and we could talk in a quieter environment for half an hour. They also brought me books and writing paper, which dramatically improved my situation. This cell also had a raised commode which made going to the toilet a lot easier. It was then that I started making friends with the sparrows outside my cell. I made a bird table out of discarded cardboard, which I transferred to another cell, the day I left. My fellow prisoner promised to look after my sparrows. My bloodied (and later washed) panjabi has still not been returned to me. [caption id=“attachment_5679071” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A woman takes pictures as journalists and activists protest against the arrest of photojournalist Shahidul Alam, as Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina attends the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York, this September. REUTERS[/caption] Interestingly, your legal team secured your bail from the High Court only after at least four failed attempts. Several judges felt “embarrassed” to simply hear your bail petition, let alone deciding whether to grant you bail. What does this tell us about our judiciary? While authoritarian governments rule all South Asian countries and lawyers complain of the lack of separation between the judiciary and the state, the Indian judiciary has sometimes taken a bold position. Supreme Court judge Dhananjaya Yeshwant Chandrachud’s recent observation — “Dissent is the safety valve of democracy. If you don’t allow the safety valve, the pressure cooker will burst” — is encouraging. While I have not come across Bangladeshi judges taking such a stand, the bench that did eventually grant me bail did not fail to observe that what I have been accused of saying is “inconsistent” with what I have actually said. This gives me hope. I am an optimist and continue to believe, that if the people lead the way, the judiciary will find its voice. It happened in 2010, when the government had closed down my exhibition, Crossfire, on extrajudicial killings. Bolstered by a public outcry against the closure, the court was prepared to rule against the government which then backed off and let the show go on. Things are a lot worse now, but one cannot give up hope. People however, need to continue to show the way. While you were in jail, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in an interview with Reuters accused you of being “mentally sick,” having tried to “use [the] situation and instigate it” during the student protests for safer roads. She also blamed your behaviour on your family background, more specifically one of your deceased great-uncles. Back then, you had little chance to respond to those charges, but now you do. I’d like to start off by saying that Reuters had sought my partner Rahnuma Ahmed’s response and she had written back, “The police have filed a case against Shahidul, investigation is already underway, in such a situation, I don’t think people in positions of power should be saying things which could be read as attempts to imperil the investigation or to influence the judiciary.” For some reason, I know not what, Reuters chose not to include it in their story, although what she said is meaningful. To come to relatives, as Salil Tripathi says, “One does not choose one’s (blood) relatives. One chooses one’s friends.” And while it’s true that my great-uncle, my maternal grandmother’s brother, to be precise, Abdus Sabur Khan — by the way, I do not share his politics at all, I’m very critical of it — was a war collaborator, different members had different political leanings, as often happens in families. Sabur Khan’s elder brother was Abdul Ghani Khan, and they contested from the same seat in the 1954 elections: Abdul Ghani Khan stood from the United Front, and Khan Sabur Khan from the Muslim League. Family lore has it that the elder brother arranged for a woman dressed in a burqa, to impersonate their mother and canvass for him. The tactic seems to have paid off, for Abdul Ghani Khan won with a big margin. The Awami League was formed later, and as far as I know, he was one of its founding members. Interestingly, family history also has it, that in 1972, when Sabur Khan was in jail for war crimes, he was visited by my grandmother and Abdul Ghani Khan and given 10,000 taka which had been sent by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Cherry picking from history is convenient, but deliberately misleading. But I must thank my friends in Bangladesh and worldwide, who demonstrated their courage and integrity when they stood by me despite the attempts to malign my reputation. As for “instigation,” I reported on events that had already taken place, so how can I be guilty of provoking them? I would advise readers who haven’t viewed it to see the meticulous reconstruction, and correlation of events on the ground, with my Facebook Live posts of 4 August, by investigative journalist Tasneem Khalil. It clearly demonstrates that I had posted reports of events after they had occurred. The only ‘crime’ I can be accused of having committed is that of journalism. I think the allegation of ‘instigation’ just goes to show that those who accuse me are not bothered by the logic of ‘cause’ and ’effect’. Lastly, sickness is defined by perceptions of health. Where sycophancy, spinelessness and subservience are the norm, being vocal and speaking the truth will be diagnosed as sickness. I hope this sickness is viral and turns into a plague.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)