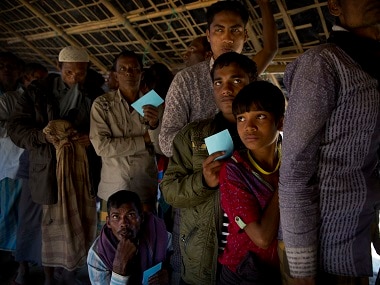

Donor fatigue, an exasperated government, a community in despair and increasingly strained ties with the locals have come to define the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh. This complex picture is seldom discussed in the media, which is driven by developments of the day. A combination of events is making the situation worse. Since August 2017, Bangladesh is providing food and shelter to almost 1.1 million Rohingya Muslims who fled ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. The government has recently made it clear that it will not accept any more refugees, though a small number of Rohingya are still arriving in Bangladesh. [caption id=“attachment_4314313” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  File image of Rohingya refugees. AP[/caption] Snaking queues of hundreds and thousands of desperate people scrambling to cross the border, which prompted a global outcry in 2017, have dried up; so has the media attention. The sense of urgency evoked by the crisis, described as the worst humanitarian disaster by the United Nations, has vanished. Condemnation of the Myanmar military and the civilian authorities, including Aung San Suu Kyi, has not led to concerted international action. It is business as usual not just for the principal backers of the Myanmar government, China and Russia, but also for other regional and global powers. That a genocide was in the making for quite some time while the international community was cheering democratisation of Myanmar is no longer a revelation. Yet, no responsibility has been fixed, nor lessons learnt. The long-drawn process of holding the Myanmar regime accountable for the genocide has started at the International Criminal Court (ICC). A team from the ICC prosecutor’s office recently visited the refugee camps. The ICC is conducting a preliminary examination, far from an investigation, let alone a trial. The developments offer little comfort to the refugees living in squalid conditions in the makeshift camps in the hill districts of Cox’s Bazaar. Twenty-one months since the crisis began, the plight of the Rohingya has worsened despite the efforts of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration and several international NGOs. Even the most optimistic now concede that an imminent repatriation is an unrealistic expectation. In March, the UN secretary general’s special envoy for Myanmar, Christine Schraner Burgener, said she saw no immediate solution to the crisis. The Bangladesh government has been saying the same since early this year. Yet, the funds to help the Rohingya are dwindling. According to UNHCR officials, only 14% of the $920 million needed under the third joint response plan (JRP) had been pledged by various countries until late March. In 2018, only 64% of the requested $951 million were received. If funds don’t come, Bangladesh and the UNHCR will be in a spot by the end of the year. Donor fatigue, along with their own missteps, have put the Bangladeshi authorities in a serious problem. It recently revived the proposal for a safe zone inside Myanmar. Suggested by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in her UN general assembly address in September 2017, the proposal was not pursued vigorously by Bangladesh. Of course, the likelihood of the UN approving it was slim, thanks to China and Russia. So, instead of building a global coalition to pressure Myanmar, Bangladesh opted for a bilateral agreement in September 2017, sidestepping the international community. The agreement set a two-year time frame for repatriation. Myanmar has found ways to block the return of the Rohingya, who it sees as illegal migrants from Bangladesh, and Dhaka can’t force a repatriation. The agreement, for all intents and purposes, is dead. A perturbed Bangladesh is now turning to Western nations at the UN for a solution, but help is unlikely to be forthcoming. Bangladesh’s close friends, China and India, have not come to its aid either. Neither country, for instance, has contributed to this year’s JRP. Worse, some Rohingya who took shelter in India decades ago, have crossed into Bangladesh, fearing that Indian authorities will send them back to Myanmar. Turkey and the countries of the Gulf and West Asia, too, have failed to come good on aid. Faced with international criticism and refugees’ resistance, the Bangladesh government has decided to go slow on a plan to relocate about 100,000 Rohingya to a remote flood-prone island called Bhasan Char (floating island), where several houses have been constructed. The UN has given a conditional nod to the relocation plan. But, there is also apprehension that the move will send a message that Bangladesh has, in fact, accepted the refugees, and the government is very sensitive to such signalling. The uncertainty only adds to the refugees’ problems. The camps have only 1,200 educational centres for 381,000 children below the age of 14. This means that the young are deprived of education and also a chance to develop skills that will help them lead a better life. The problem was thrust into public glare when early this month some Rohingya children were expelled from schools outside the camps. With little to do in the camps, youth are turning to drug abuse and smuggling. Considering that these camps are on the Myanmar-Bangladesh yaba drug smuggling route, this does not portend well for the country. Even before the refugee crisis, the Rohingya were vulnerable to human trafficking; the situation has only worsened. But, the biggest problem is the growing animosity between the refugees and local residents. Increasingly worried about their interests, the locals have demanded that the Rohingya be sent back or dispersed throughout the country, a demand unlikely to be supported by the international community or the government. Their concerns are borne out by the ‘2019 Global Report on Food Crises’ of the Global Network against Food Crises, which says the locals in Cox’s Bazar are facing increased food insecurity due to the Rohingya influx. Sporadic clashes between the locals and the refugees are a matter of concern for the stability in the camps and nearby areas. The crisis is worsening, even as the international community watches from the sidelines. The lip-service of compassion is not enough, it reminds us that the world is failing the Rohingya. Hopelessness, uncertainty, despair and lack of resources are creating a generation which can be ignored only at our peril. (Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University)

Dwindling funds, lack of support from global powers and strained ties with locals have put the Rohingya in a spot

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)