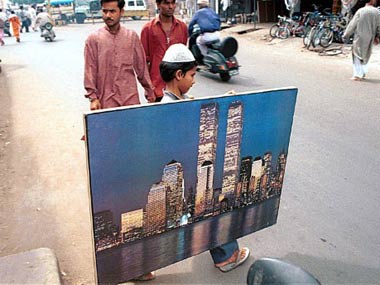

By Shiv Visvanathan The 9/11 attacks will be a decade old on Sunday. If a week is a long time in politics, a decade is a long time in history. The passage of time has anointed 9/11 with the status of the myth. It is now presented as the ultimate sacrament of global politics, the day when America discovered terror. Till then terror was what happened to the other: the Lebanese, the Israeli, the Pakistani, the Indian. With 9/11, America became both a global power and global in sensitivity. No other event has been subject to such repetition. It is a record played again and again, like a liturgy, a litany as it moves between eternity and redundancy. Some call it the American Suprabhatam. For Indians watching the attacks 1o years ago, the attacks had all the power of a postcard, the drama of watching an event frozen at a distance. But a cameo viewed at a distance did not suffice. We are a nation that loves audience participation. We needed to be involved. Our sense of connect comes from always claiming kinship or affinity. We recognise an event by claiming a cousin as a witness or a friend as a bit player. And soon we became an active chorus, a sentimental side-act to main drama when we discovered that Indians had died in the Twin Towers. [caption id=“attachment_79881” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“The moment of tragedy was also the moment we became a part of the American melting pot. India could claim that the American tragedy was also an Indian one. AFP”]  [/caption] We almost treated it as a demographic dividend when the New York Times proclaimed that Indians were “the third largest ethnic group" in the 9/11 tragedy. These tragic anecdotes were retailed as a show of solidarity. One recollects the case of Joseph Mathai, who had gone to attend a conference at the World Trade Centre. He messages his family that very day and that is the last that is heard of him. Joseph’s brother Cherian gave a DNA sample so his brother’s body could be identified. Even a year later, the mourning continued when Prime Minister Vajpayee met the relatives of victims at a hushed meeting. He allowed them their moment of mourning and grief. Gracious in his speech, he said “there were 2,800-odd victims at World Trade Center. Of that 117 were of Indian origin and 70 were Indians. Each of the families gathered here has a sad tale to narrate. Let them say it in their own words.” But it is the little events that one remembers. 9/11 had not yet inaugurated the era of the Internet. The most significant memory is the clogged telephone line, the sense of concern and worry that a friend or relative could not be reached. The sense of helplessness echoed our sense of solidarity with the Americans at a human level, even as our minds were working overtime to ask what does it mean? The moment of tragedy was also the moment we became a part of the American melting pot. India could claim that the American tragedy was also an Indian one, and grief united us in a way politics never could. The attacks bound us together at the level of personal drama, but not at the level of politics. Racial profiling made us part of the threat and the backlash against Indian taxi drivers, and Sikhs in particular, was brutal. India was caught in ambivalence, ready to grieve at one end and forced to acknowledge the brutality against our kind. America felt it had been ambushed by the world and turned inward. The American dream became a nightmare as hate crimes against Indians became rampant. 9/11 spontaneously brought out the American in all of us till the American reaction forced us to recognise the Muslim in all of us. Continues on the next page Grief and mourning soon yielded to doubt and concern. There was a sense of a new epoch in terrorism. Suddenly, the terrorist looked different. He was no longer the ugly savage, the lethal brute, but the quiet assassin, technically competent, multi-lingual, at home in many worlds, ready to pit professional skill against technocratic might. The image of the terrorist changed from a push-button figure to a professional ready to destroy. As a crowd of spectators, we provided the chorus of mourning, but as thinking Indians we realised that this new version of terrorism and fundamentalism would make democracy even more problematic. India’s collective consumption of 9/11 as a public drama had a split level quality to it. At one level, there was the question of what does this mean for South Asia and secondly what does it mean for us? A question that has the inevitable addendum: Will US see Pakistan in true light? There was an anticipatory smugness that Pakistan’s luck would run out. Pakistan had become a rogue state while India needed to be recognised as a mature regime. Unfortunately, India’s ‘good boy’ theory of itself cut little ice. Pakistan may have fallen into fragments, but the American support for the regime has remained strong as ever. What was critically missing in our view of 9/11 was a sense of India in global terms. The anecdote and the sentiment dominated the real politik analysis required. India’s piety once again blurred its political lenses making it look silly and incompetent. It was a moment when we should have realised a nation does not change paradigms in a crisis. Ostrich like, it can get deeper into cliché. This was the Indian farce in response to the American tragedy. Ten years have not taught us much. Shiv Visvanathan is a Social Science nomad.

The 9/11 attacks are no longer an event, but a religious liturgy, played again and again like a record. The distance of time reveals America’s follies of interpretation — and also ours.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by FP Archives

see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)