On 8 January 2013, Rajat Gupta, former head of McKinsey & Co, will go to jail for two years and pay a fine of $5 million after being convicted for insider trading. His basic crime was not that he made money from insider information, but that he passed information on to Raj Rajaratnam, who was convicted earlier in October 2011 , and began his 11-year prison sentence the following month.

Only one part of the two sentences - the financial penalties - makes any sense, for insider trading is actually an esoteric, victimless crime. No one should be going to jail for making money - or not losing money - merely on the basis of access to information.

Let us first understand that insider trading really is, and why there are no victims in this crime.

Using a commonsense meaning of the term insider, it means anyone working for a company, or an associate or a vendor or even an analyst with access to non-publicly available information on a company that could, theoretically, impact the stock price one way or the other.

When an insider trades on the information he or she has, the assumption is that the other party to the deal - the one who buys or sells shares to him or her - is an innocent who does not have the same privileged access to information.

This is very dubious logic for the following reasons.

First, the insider himself may or may not make a profit or avoid a loss, since the stock market does not move on the basis of a single piece of information. Many factors go into the making of a price, including market sentiment, demand and supply of stock, industry and economic trends, and stock-specific developments. There is no one-to-one correlation between insider info and an insider’s gains or losses.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsSecond, the insider may have an advantage in terms of information, but markets always have two parties to the deal: buyers and sellers. If an insider buys a share with the benefit of inside info, one can say that the sellers are disadvantaged, but all unwitting buyers - the ones who were not insiders on the day an insider bought the shares - would also have benefited. So the balance of losses and gains from inside information are not that skewed. Insider info also benefits some categories of investors, especially in these days of algorithmic trading and technicals-driven trading, where a spike in shares tends to draw more investors into a stock.

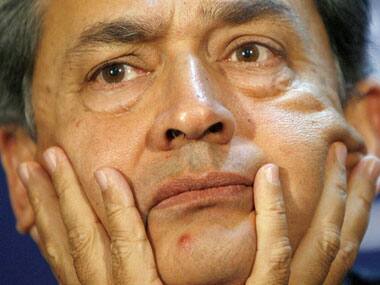

[caption id=“attachment_502150” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

The judge is effectively saying that Gupta’s real crime was that he disclosed what was discussed on Goldman Sachs’ board to outsiders - which was his breach of trust. Reuters[/caption]

The judge is effectively saying that Gupta’s real crime was that he disclosed what was discussed on Goldman Sachs’ board to outsiders - which was his breach of trust. Reuters[/caption]

Third, even if an insider buys the stock of a company on the basis of inside info, the fact remains that he is not forcing any unwary investor to sell against his will. Whatever the circumstances, the counter-party to the insider deal is selling a share because he wants to, for his own reasons. He is a victim only if one stretches the meaning of the term.

In fact, Judge Jed Rakoff, the man who sentenced Rajat Gupta to a “lenient” two years in prison yesterday, makes a pointed reference to the fact that even in the US, sentencing on insider trading is not based on the theory that someone made a loss or gain due to the actions of an insider (read the highlights of his judgment here ).

He said in his judgment: “While insider tradingmay work a huge unfairness on innocent investors, Congress has nevertreated it as a fraud on investors, the Securities ExchangeCommission has explicitly opposed any such legislation, and theSupreme Court has rejected any attempt to extend coverage of thesecurities fraud laws on such a theory…”.

So if loss to investors, or fraud, in not the basic reason for convicting Rajat Gupta, what is? Says Judge Rakoff: “The heart of Mr Gupta’s offenses here, it bears repeating,is his egregious breach of trust. Mr Rajaratnam’s gain, though aproduct of that breach, is not even part of the legal theory underwhich the government here proceeded, which would have held Guptaguilty even if Rajaratnam had not made a cent.”

(Rajaratnan was convicted last October for buying and selling Goldman Sachs shares based on information provided by Rajat Gupta, who was on the investment banker’s board.)

The judge is effectively saying that Gupta’s real crime was that he disclosed what was discussed on Goldman Sachs’ board to outsiders - which was his breach of trust.

If this is the case, it should be Goldman Sachs suing Gupta, and not the Securities and Exchange Commission or Uncle Sam.

The judge says as much: “In the eye of the law,Gupta’s crime was to breach his fiduciary duty of confidentiality toGoldman Sachs; or to put it another way, Goldman Sachs, not themarketplace, was the victim of Gupta’s crimes as charged. Yet the(sentencing) guidelines assess his punishment almost exclusively on the basis ofhow much money his accomplice gained by trading on the information.At best, this is a very rough surrogate for the harm to GoldmanSachs.” (As an aside, we may add that Goldman Sachs did not lose anything by this).

The larger point is this: given the fact that the market always reacts to trading trends and volumes, is insider trading all bad? When an insider trades and sends prices up (or down), the market takes note. If an important bit of news is going to impact the stock, is it better for the market and investors to wait for a formal announcement on the same, or is it better to figure out something is afoot based on the hidden signals of the insider traders?

The central argument for punishing insider traders is information asymmetry - one man has info which other don’t. If we use this logic, we should ban all branded products. For example, a generic drug is sold at one price, while a branded product made from the same active pharmaceutical ingredient is priced several times higher. But this is legal.

A Tiruppur-made hosiery product is rebranded by an international textile label and sold at several times the basic market price. The consumer pays more because he does not know that the same manufacturer makes the vest sold for Rs 100 in Tiruppur as the one sold by, say, Tommy Hilfiger, for two-and-a-half times the price. The margin comes from information asymmetry - the same way it does for insider traders.

As we noted earlier in the Raj Rajaratnam case, the case for hard treatment of insider trades is based on flaky premises. This writer does not believe that Rajaratnam deserves 11 years in prison for his insider trades, just as he don’t agree that Gupta deserves his two years in jail.

As Firstpost noted then: “Some free-marketers go so far as to say that insider trading should, in fact, be encouraged or else the market would not know something was in the air. The late Milton Friedman, an Economics Nobel winner, said in 2003: “You want more insider dealing, not less. You want to give people most likely to have knowledge about deficiencies of the company an incentive to make the public aware of that.”

Knowledge@Wharton , an online journal of the Wharton School of Business in Pennsylvania, also quotes an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal: “Far from being so injurious to the economy that its practice must be criminalised, insiders buying and selling stocks based on their knowledge play a critical role in keeping asset prices honest - in keeping prices from lying to the public about corporate realities.”

Both Friedman and The Wall Street Journal are saying that insider trades send an important signal to the markets. More information is flowing in, and which can only improve price discovery.

To be sure, this is not to say let’s legalise insider trading: that is not the point. But the punishment for insider trading should be related to the gains made or losses avoided. Sending a man to jail for a “victimless crime” - a crime that may actually improve the efficiency of the markets and price discovery - is pointless. The ends of justice are better served by confiscating the insider’s financial gains, and even adding a fine to it.

)