Pakistan’s financial woes continue to deepen as the country’s total public debt soared to an all-time high of PKR 76,007 billion, according to the Economic Survey 2024–25 released on Monday. The figure, equivalent to ₹23.1 trillion in Indian rupees or approximately USD 269.3 billion, reveals how the debt burden has nearly doubled in just four years, up from PKR 39,860 billion in 2020–21.

The report paints a stark picture of the country’s fiscal health, warning that “excessive or poorly managed debt can pose serious vulnerabilities, such as rising interest burdens and can undermine long-term fiscal sustainability and economic security if left unaddressed.” A decade ago, the country’s public debt stood at PKR 17,380 billion, meaning the debt has ballooned nearly fivefold over ten years.

Of the total PKR 76 trillion, domestic debt accounts for PKR 51,518 billion, while external debt stands at PKR 24,489 billion.

Addressing the media on survey reports, Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb offered a partial defence. He pointed out that Pakistan’s public debt-to-GDP ratio has come down from 68% to 65%, and that some macroeconomic indicators had begun to stabilise.

Aurangzeb said the country’s forex reserves as of June 30, 2024, stood at $9.4 billion—“a huge and remarkable recovery” compared to 2023, when reserves had dropped to the point where they covered barely two weeks of imports. “The recovery after June 30 continued and we consolidated it in 2024–25,” he added.

On monetary policy, he said that Pakistan had earlier maintained a record-high interest rate of 22% in 2023, but “steps were taken” to bring it down. The policy rate now stands at 1,100 basis points, or 11%.

Impact Shorts

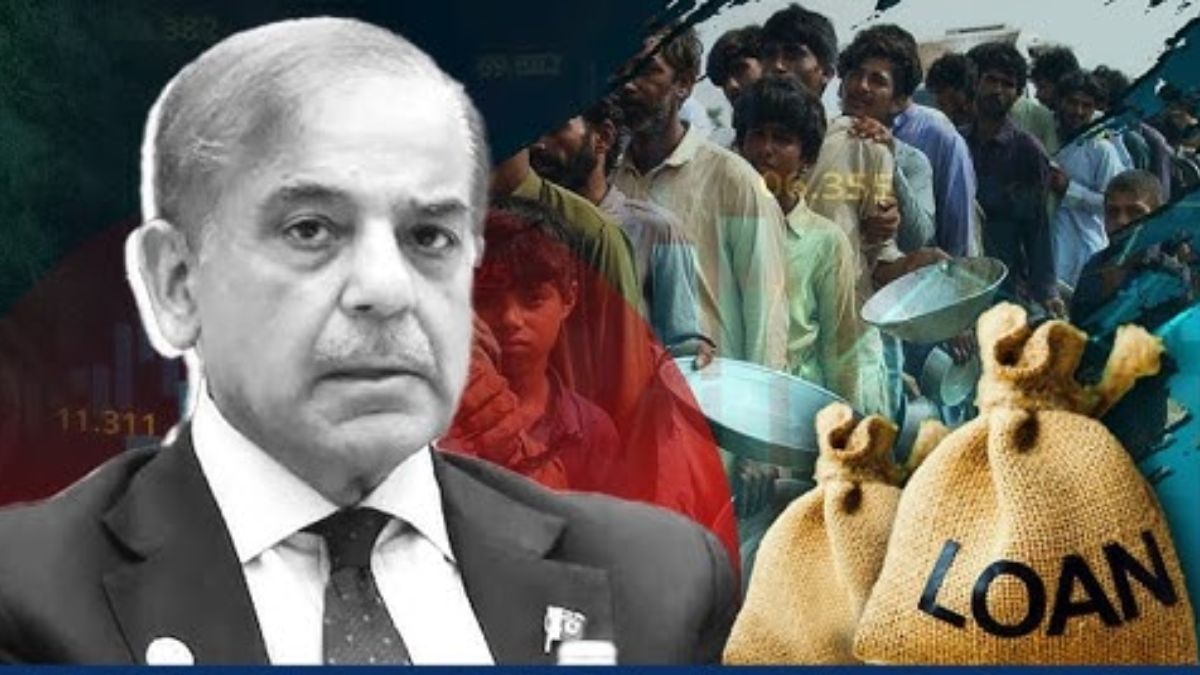

More ShortsPakistan has also received $1.03 billion under the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility, part of a bailout programme crucial to avoiding default. Aurangzeb credited Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif for restoring investor confidence: “Our credibility and trust were re-established under Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s leadership.”

Despite these reassurances, the broader picture remains grim. The public remains wary of Pakistan’s frequent appeals to international lenders and so-called friendly countries. Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif himself has acknowledged the crisis, remarking recently, “Today, when we go to any friendly country or make a phone call, they think that we have come to them to beg for money.”

In another candid moment, Sharif said, “Even small economies have surpassed Pakistan, and we have been wandering for the past 75 years carrying a begging bowl.”

)