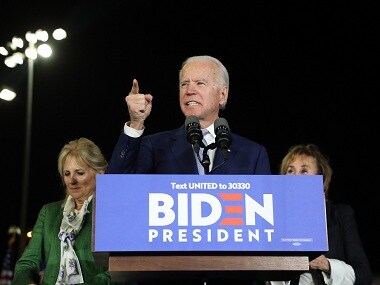

The Democratic presidential race emerged from Super Tuesday with two clear front-runners as Joe Biden won Virginia, North Carolina and at least six other states, largely through support from African-Americans and moderates, while Senator Bernie Sanders harnessed the backing of liberals and young voters to claim the biggest prize of the campaign, California, and several other primaries. The returns across the country on the biggest night of voting suggested that the Democratic contest was increasingly focused on two candidates who are standard-bearers for competing wings of the party, Biden in the political Centre and Sanders on the Left. Their two other major rivals, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Michael Bloomberg, were on track to finish well behind them and faced an uncertain path forward. Biden’s victories came chiefly in the South and the Midwest, and in some of them he won by unexpectedly wide margins. In a surprising upset, Biden even captured Warren’s home state of Massachusetts, where he did not appear in person, and where Sanders had campaigned aggressively in recent days. Sanders easily carried his home state of Vermont and was locked with Biden and Warren of Massachusetts in a competitive race in her home state. Biden’s early lead in the South could well be offset by victories in Western states later: Sanders was expected to perform strongly in California, the most important prize of the night, where recent polls had shown him with a solid lead over Biden. As he did in South Carolina, Biden rolled to victory in the four Southern states thanks in large part to black voters: More than 60 percent of African-Americans voted for him. Just as worrisome for Sanders, in Virginia and North Carolina — two states filled with suburbanites — Biden performed well with a demographic that was crucial to the party’s success in the 2018 midterm elections: College-educated white women. “We were told, well, when you got to Super Tuesday, it’d be over,” a triumphant Biden, 77, said at a celebration in Los Angeles. “Well, it may be over for the other guy!” After a trying stretch in February, even Biden appeared surprised at the extent of his success. “I’m here to report we are very much alive!” he said. “And make no mistake about it, this campaign will send Donald Trump packing.” [caption id=“attachment_8115451” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] Former vice-president Joe Biden speaks at a campaign event in Los Angeles on Super Tuesday. By Josh Haner © 2020 The New York Times[/caption] Sanders continued to show strength with the voters that have made up his political base: Latinos, liberals and those under age 40. But he struggled to expand his appeal with older voters and African-Americans. The unexpected breadth of Biden’s success on Tuesday illustrated the volatility of this race as well as the determination of many center-left Democrats to find a nominee and get on to challenging Trump. The former vice-president had little advertising and a skeletal organisation and scarcely even visited many of the states he won, including liberal-leaning Minnesota and Massachusetts. But his smashing victory in South Carolina echoed almost instantaneously, and his momentum from there proved far more powerful than the money Sanders and Bloomberg had poured into most of Tuesday’s contests. The early returns were a comprehensive setback for Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City who entered the race late and spent more than half a billion dollars on an aggressive advertising campaign. But Bloomberg slumped badly after a series of damaging clashes with Warren, and many moderates and African-Americans appeared to have abandoned him for Biden. Hours into vote-counting, Bloomberg had won only one contest, in American Samoa. Addressing supporters in West Palm Beach, Florida, on Tuesday night, Bloomberg tried to put the best face on a dismal evening. “Here’s what is clear,” he said. “No matter how many delegates we win tonight, we have done something no one else thought was possible: In just three months, we’ve gone from one percent in the polls to being a contender for the Democratic nomination for president.” Warren’s loss in Massachusetts left her without a single victory after a month of primaries and caucuses, and in many places on Tuesday she was running in a relatively distant third or fourth place. Most dispiriting to Warren may be that it was not Sanders, who worked hard to defeat her in her home state, but rather Biden, who bested her in Massachusetts, suggesting that none of the recent tumult in the race had worked to her advantage. But Warren’s campaign in recent days explicitly laid out a strategy of accumulating delegates for a contested convention, and it was not clear that her latest setbacks would deter that approach. Warren campaigned Tuesday in Michigan, which holds a primary next week, and urged voters to “cast the vote that will make you proud” rather than making more calculated assessments. And she has announced campaign stops in Arizona and Idaho, two other states that vote later this month. At Sanders’ campaign party in Vermont on Tuesday night, he answered Biden’s surge in the race with a battle cry for his supporters: He proclaimed “absolute confidence” that he would win the Democratic nomination, and delivered a scathing critique of Biden’s record that left little doubt he would confront Biden’s revived candidacy in blunt terms in the coming days. Without naming the former vice-president, Sanders said there was another candidate in the race who had supported the invasion of Iraq, endorsed cutting Social Security, voted for international trade deals and “represented the credit card companies” by backing a 2005 overhaul of the bankruptcy code. As for himself, Sanders said, he had stood on the opposite side of every issue. “You cannot beat Trump with the same-old, same-old kind of politics,” Sanders said. “What we need is a new politics that brings working-class people into our political movement.” Sanders was on track to rack up delegates in California, but he was sharing some of them with Biden in his own state of Vermont. And in Colorado, another state Sanders carried, he was dividing them four ways, as he, Biden, Bloomberg and Warren all reached the 15 percent threshold to win delegates there. The voting followed an extraordinary reframing of the race in the past 48 hours, as moderate candidates came together to form a united front against Sanders, a democratic socialist whose general election prospects are viewed skeptically by much of the party leadership. Biden’s overwhelming victory in South Carolina on Saturday established him as the clear front-runner in the Democrats’ centrist wing, prompting two rivals, Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and former Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, to end their bids and throw their support to Biden. As Sanders, 78, returned to Vermont, where he voted Tuesday morning, his allies acknowledged that they had been caught off guard by the swiftness with which Biden’s former adversaries had locked arms to oppose Sanders’ campaign. They argued that Sanders was still far better equipped — financially and in his campaign organization — than Biden to compete for the nomination over a long primary race. And they vowed to highlight to voters the sharp differences in their agendas. Bloomberg had poured millions of dollars from his personal fortune into TV ads in the two states and made repeated appearances in both, with his advisers holding out the most hope in North Carolina. And while he has been more focused on liberal states, Sanders made multiple stops in Virginia and North Carolina in the weeks after the New Hampshire primary last month. The Democratic campaign barreled into Super Tuesday in a state of extraordinary flux, as a loose alliance of party leaders, elected officials and centrist voting blocs have seemed to fall in behind Biden since his weekend triumph in South Carolina. On Monday night, Biden made appearances in Texas with three former rivals — Klobuchar, Buttigieg and former Representative Beto O’Rourke — who are now supporting his candidacy, while Sanders rallied supporters in Minnesota in an effort to capture Klobuchar’s home state. Few presidential candidates have endured the political roller coaster Biden has found himself riding in recent weeks. After finishing a distant fourth in Iowa and then coming in fifth in New Hampshire, he was short on money, in danger of losing support to Bloomberg and facing a do-or-die primary in South Carolina. Yet after shaking up his campaign and installing a longtime adviser, Anita Dunn, as his chief strategist, Biden was able to claw back into contention by finishing second in Nevada. Then, after two solid debate performances during which his ascendant rivals were the ones under attack, he picked up a crucial endorsement: Representative James Clyburn, the highest-ranking African-American in Congress and the most influential South Carolina Democrat, came out for Biden at an emotional news conference. With Clyburn’s imprimatur, Biden built a considerable advantage with black voters that propelled him to a 28-point rout in South Carolina. Bloomberg, the wealthy former mayor of New York City, has been a pervasive presence in the race: He has run more than half a billion dollars in paid advertising since he announced his campaign in November, offering himself to the Democratic establishment as a potential savior if Biden failed to halt Sanders in the earliest primaries and caucuses. Yet Bloomberg’s prospects were uncertain heading into Super Tuesday, after his disastrous performance in a debate last month in Las Vegas and Biden’s resurgence in the polls. Bloomberg’s campaign publicly signaled he planned to forge ahead even if he faced a disappointing night, announcing plans to stump later this week in Pennsylvania and Michigan, and holding his election-night event in Florida, which holds a primary in two weeks. But advisors to Bloomberg have also acknowledged that the former mayor would make a cold assessment of his options once the results of Super Tuesday became known. He is likely to face intense pressure to make way for Biden if his self-funded candidacy does not yield impressive results. Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns c.2020 The New York Times Company

Former vice-president Joe Biden speaks at a campaign event in Los Angeles on Super Tuesday. By Josh Haner © 2020 The New York Times[/caption] Sanders continued to show strength with the voters that have made up his political base: Latinos, liberals and those under age 40. But he struggled to expand his appeal with older voters and African-Americans. The unexpected breadth of Biden’s success on Tuesday illustrated the volatility of this race as well as the determination of many center-left Democrats to find a nominee and get on to challenging Trump. The former vice-president had little advertising and a skeletal organisation and scarcely even visited many of the states he won, including liberal-leaning Minnesota and Massachusetts. But his smashing victory in South Carolina echoed almost instantaneously, and his momentum from there proved far more powerful than the money Sanders and Bloomberg had poured into most of Tuesday’s contests. The early returns were a comprehensive setback for Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City who entered the race late and spent more than half a billion dollars on an aggressive advertising campaign. But Bloomberg slumped badly after a series of damaging clashes with Warren, and many moderates and African-Americans appeared to have abandoned him for Biden. Hours into vote-counting, Bloomberg had won only one contest, in American Samoa. Addressing supporters in West Palm Beach, Florida, on Tuesday night, Bloomberg tried to put the best face on a dismal evening. “Here’s what is clear,” he said. “No matter how many delegates we win tonight, we have done something no one else thought was possible: In just three months, we’ve gone from one percent in the polls to being a contender for the Democratic nomination for president.” Warren’s loss in Massachusetts left her without a single victory after a month of primaries and caucuses, and in many places on Tuesday she was running in a relatively distant third or fourth place. Most dispiriting to Warren may be that it was not Sanders, who worked hard to defeat her in her home state, but rather Biden, who bested her in Massachusetts, suggesting that none of the recent tumult in the race had worked to her advantage. But Warren’s campaign in recent days explicitly laid out a strategy of accumulating delegates for a contested convention, and it was not clear that her latest setbacks would deter that approach. Warren campaigned Tuesday in Michigan, which holds a primary next week, and urged voters to “cast the vote that will make you proud” rather than making more calculated assessments. And she has announced campaign stops in Arizona and Idaho, two other states that vote later this month. At Sanders’ campaign party in Vermont on Tuesday night, he answered Biden’s surge in the race with a battle cry for his supporters: He proclaimed “absolute confidence” that he would win the Democratic nomination, and delivered a scathing critique of Biden’s record that left little doubt he would confront Biden’s revived candidacy in blunt terms in the coming days. Without naming the former vice-president, Sanders said there was another candidate in the race who had supported the invasion of Iraq, endorsed cutting Social Security, voted for international trade deals and “represented the credit card companies” by backing a 2005 overhaul of the bankruptcy code. As for himself, Sanders said, he had stood on the opposite side of every issue. “You cannot beat Trump with the same-old, same-old kind of politics,” Sanders said. “What we need is a new politics that brings working-class people into our political movement.” Sanders was on track to rack up delegates in California, but he was sharing some of them with Biden in his own state of Vermont. And in Colorado, another state Sanders carried, he was dividing them four ways, as he, Biden, Bloomberg and Warren all reached the 15 percent threshold to win delegates there. The voting followed an extraordinary reframing of the race in the past 48 hours, as moderate candidates came together to form a united front against Sanders, a democratic socialist whose general election prospects are viewed skeptically by much of the party leadership. Biden’s overwhelming victory in South Carolina on Saturday established him as the clear front-runner in the Democrats’ centrist wing, prompting two rivals, Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and former Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, to end their bids and throw their support to Biden. As Sanders, 78, returned to Vermont, where he voted Tuesday morning, his allies acknowledged that they had been caught off guard by the swiftness with which Biden’s former adversaries had locked arms to oppose Sanders’ campaign. They argued that Sanders was still far better equipped — financially and in his campaign organization — than Biden to compete for the nomination over a long primary race. And they vowed to highlight to voters the sharp differences in their agendas. Bloomberg had poured millions of dollars from his personal fortune into TV ads in the two states and made repeated appearances in both, with his advisers holding out the most hope in North Carolina. And while he has been more focused on liberal states, Sanders made multiple stops in Virginia and North Carolina in the weeks after the New Hampshire primary last month. The Democratic campaign barreled into Super Tuesday in a state of extraordinary flux, as a loose alliance of party leaders, elected officials and centrist voting blocs have seemed to fall in behind Biden since his weekend triumph in South Carolina. On Monday night, Biden made appearances in Texas with three former rivals — Klobuchar, Buttigieg and former Representative Beto O’Rourke — who are now supporting his candidacy, while Sanders rallied supporters in Minnesota in an effort to capture Klobuchar’s home state. Few presidential candidates have endured the political roller coaster Biden has found himself riding in recent weeks. After finishing a distant fourth in Iowa and then coming in fifth in New Hampshire, he was short on money, in danger of losing support to Bloomberg and facing a do-or-die primary in South Carolina. Yet after shaking up his campaign and installing a longtime adviser, Anita Dunn, as his chief strategist, Biden was able to claw back into contention by finishing second in Nevada. Then, after two solid debate performances during which his ascendant rivals were the ones under attack, he picked up a crucial endorsement: Representative James Clyburn, the highest-ranking African-American in Congress and the most influential South Carolina Democrat, came out for Biden at an emotional news conference. With Clyburn’s imprimatur, Biden built a considerable advantage with black voters that propelled him to a 28-point rout in South Carolina. Bloomberg, the wealthy former mayor of New York City, has been a pervasive presence in the race: He has run more than half a billion dollars in paid advertising since he announced his campaign in November, offering himself to the Democratic establishment as a potential savior if Biden failed to halt Sanders in the earliest primaries and caucuses. Yet Bloomberg’s prospects were uncertain heading into Super Tuesday, after his disastrous performance in a debate last month in Las Vegas and Biden’s resurgence in the polls. Bloomberg’s campaign publicly signaled he planned to forge ahead even if he faced a disappointing night, announcing plans to stump later this week in Pennsylvania and Michigan, and holding his election-night event in Florida, which holds a primary in two weeks. But advisors to Bloomberg have also acknowledged that the former mayor would make a cold assessment of his options once the results of Super Tuesday became known. He is likely to face intense pressure to make way for Biden if his self-funded candidacy does not yield impressive results. Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns c.2020 The New York Times Company

On Super Tuesday, Joe Biden wins eight States on strength of Black voters, but Bernie Sanders clinches California

The New York Times

• March 4, 2020, 12:00:41 IST

Joe Biden secured an early advantage on a pivotal night of Democratic primary voting on Tuesday with victories in four Southern states — Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Alabama

Advertisement

)

End of Article