The news that the poliovirus has been found circulating in city wastewater fuelled a wide range of reactions in city parents Monday. Some were unfazed. Others were terrified. Public health officials, however, had a simple message for them: Get your children vaccinated. If they are vaccinated, they are safe. In South Williamsburg, a largely Hasidic enclave in Brooklyn where the polio vaccination rate among 5-year-olds is the lowest in the city, mothers in playgrounds pushed swings and watched their children play. With only one case found so far, in a Rockland County resident who became paralyzed, several mothers said they thought of the situation as something to watch out for, but not an imminent threat. “It is concerning,” said South Williamsburg resident Esther Klein, 24, who is Hasidic and mother of a 1-year-old son. “I want to make sure his vaccines are updated.” What would make her alarmed, she said, is if more people started getting sick. In nearby Domino Park, a few mothers said their paediatricians had reassured them that their children would be fine because they are vaccinated. But Elsa de Berker, 32, said she was fearful for her daughter, who is turning 2 soon, even though her polio vaccines are up to date: “It’s terrifying.” As some parents anxiously called paediatricians offices to ask for guidance and to schedule vaccination appointments Monday, they were largely reassured: As long as they keep their children on the standard immunisation schedule, their children should be protected.

The polio vaccine is highly effective.

A first dose is typically given when babies are 2 months old; a second is given two months later. After those two doses, protection against paralytic polio is at least 90 per cent. A third dose is typically given when the baby is six months old. That dose brings protection against paralytic polio close to 99 per cent. A fourth dose, given after the child turns 4, is intended to ensure that the high protection lasts over a lifetime. “My advice is follow the vaccine schedule, and everything will be OK,” said Dr Peter Silver, a paediatrician and associate chief medical officer for Northwell Health. “I think that if you are vaccinated, you are not at significant risk. The population at risk are the unvaccinated.” Infants younger than four months are generally protected by their mother’s antibodies, assuming their mothers are vaccinated. [caption id=“attachment_10833171” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The crippling effects of polio. The Conversation[/caption] In London, the persistent circulation of polio in wastewater since February has led to a recent recommendation that children between the ages of 1 and 9 get an additional booster dose. But the outbreak in New York has not yet reached that level of concern, according to public health officials. In addition to the case identified in Rockland County, officials have found 20 positive wastewater samples in Rockland and Orange Counties combined, and six positive samples in city wastewater in June and July. “There is no recommendation at this time that those who are fully vaccinated against polio should receive booster doses or that children undergoing their vaccine series should receive earlier or additional doses,” doctors at Weill Cornell Medicine wrote Monday in an email to reassure their patients.

Anyone unsure of their polio immunisation history is eligible to be vaccinated, including adults.

Typically, however, anyone born after 1955 will have been vaccinated to attend school. One lifetime booster dose is available for those who are particularly at risk. Although there has been only one case of paralytic polio in the New York area, health officials believe they may only be seeing “the tip of the iceberg” in terms of polio’s wider circulation, since paralytic cases are so rare. The region’s single positive case was found in an unvaccinated 20-year-old man in Rockland County. Doctors suspected acute flaccid myelitis as the cause of his leg paralysis, before he tested positive for polio in July. The infection was not travel-related, as he did not travel during the time he would have been infected, Rockland County health officials said. Although authorities have not released further biographical details about the man, local officials say he is part of the Hasidic community there. Vaccine scepticism has circulated among some in that community, and it has intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although a majority of Hasidic children are vaccinated, a significant minority are not, both because of concern about vaccines and because the pandemic has made keeping to vaccination schedules challenging, particularly for those with large families, community members said. The community is not monolithic, however, and there are ongoing tensions within it between those who resist vaccines and those who believe that such reluctance is putting the community at risk. “From my point of view, this has a lot to do with anti-vaxxers,” said Yosef Rapaport, a Hasidic media consultant and podcaster who supports vaccination. “Being late with vaccination, combined with the growth of the anti-vaxxer movement, and we are just waiting for a catastrophe,” he said. A paediatrician in Williamsburg, who spoke anonymously to avoid breaking trust with her patients, said many of the mothers she saw were worried about the safety of vaccines, because of widely circulating misinformation. They often preferred to delay doses until later in childhood, when the child’s immune system is stronger.

She said she saw the same trends when measles circulated in the community in 2019.

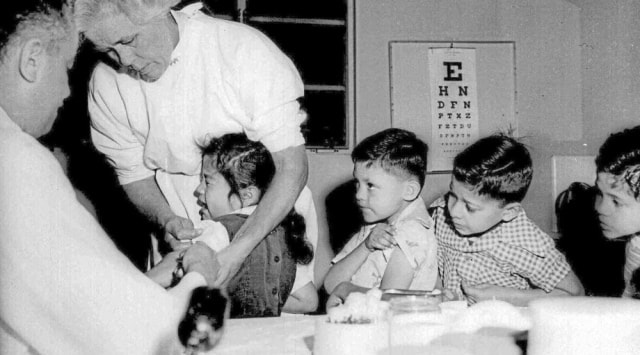

In Rockland County, health officials have been holding regular free vaccination clinics in an effort to bring rates higher. Refuah Health, one of the main primary health care providers in the area, has administered 450 polio vaccines between July 21 and Thursday, a spokesperson said. More than half of those were for children younger than 2. [caption id=“attachment_9696421” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  In this April 1955 file photo, first and second-graders at St Vibiana’s school are inoculated against polio with the Salk vaccine in Los Angeles. (AP Photo, File)[/caption] Although some providers are reporting an uptick in vaccinations in recent weeks, as of 1 August, only 60 per cent of children 2 and younger had gotten all three recommended polio shots in Rockland and Orange counties. Low rates, however, were not limited to Hasidic areas, said Irina Gelman, Orange County’s health commissioner. The rate among children 5 and younger across New York City who have three doses of the polio vaccine is 86 per cent. But vaccination by ZIP code shows much lower rates across a range of neighbourhoods, representing a diverse array of people. Close behind Williamsburg, with a vaccination rate among children younger than 5 of 56 per cent, was Battery Park City, an affluent neighbourhood in Manhattan. Other areas with low childhood vaccination rates include parts of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville, where a majority of residents are Black, and the southern tip of Staten Island, a politically conservative, mostly white area. “Wastewater sampling is not specific about the neighbourhoods where people are living who are shedding poliovirus,” said Patrick Gallahue, a spokesperson for the city’s Department of Health. New York is not planning a pop-up polio vaccination campaign, but the city is reaching out to health providers in areas where vaccination rates are low to ask them to immediately contact families with delayed vaccinations. About 93 per cent of city children younger than 5 have had at least one dose. Polio is a virus that spreads from person to person primarily through infected faeces that enters the body through the mouth. Approximately 75 per cent of people infected with polio have no visible symptoms, yet they can still spread the virus. About 25 per cent have mild symptoms, including fever, muscle weakness, headache and nausea. In about 1 in 200 cases, polio can infect a person’s brain and spinal cord, causing permanent paralysis or even death. Because of the vaccine’s success and a national vaccination program, polio cases were cut dramatically in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The last case of polio detected in the United States had been in 2013. c.2022 The New York Times Company Sharon Otterman and Nate Schweber

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)