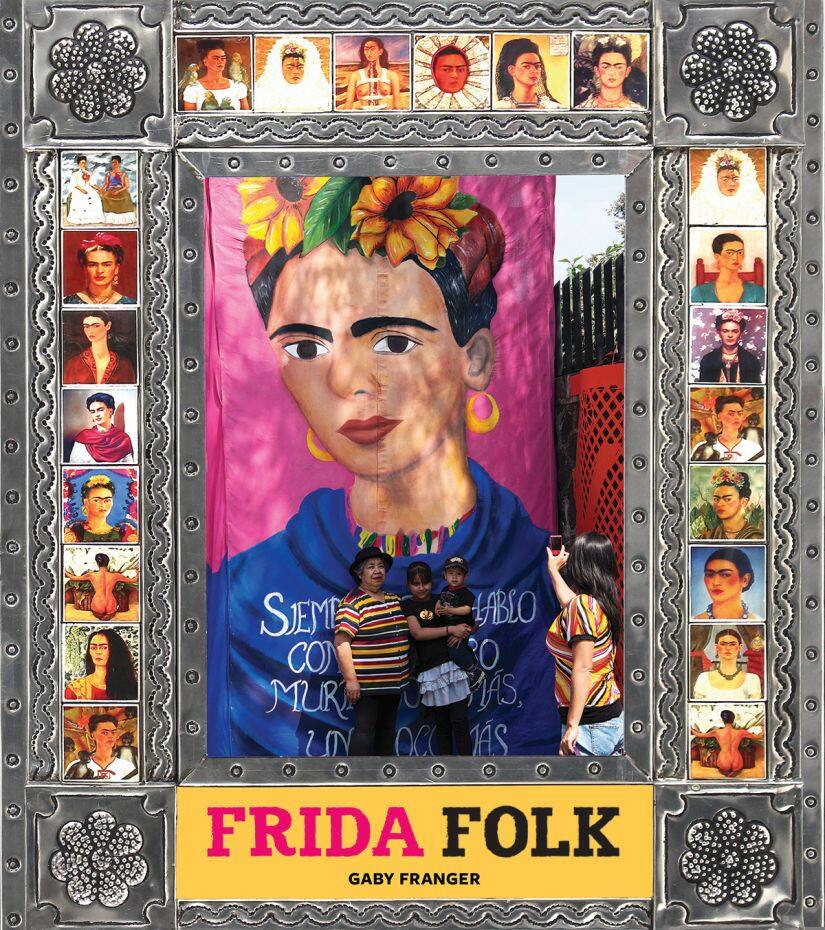

Editor’s note: Gaby Franger is an academic focussing on intercultural action projects around women’s studies. Frida Folk, her book on Frida Kahlo, features not a single original painting from the Mexican artist, but a variety of Frida objects, images, and mementos in every conceivable material, which traces some of the trails that Frida herself laid… a legacy which allows people to create their own countless versions of her. The author herself has a vast personal collection of Frida memorabilia which she has also catalogued through this project. Frida Folk is published by Tara Books in India. *** The Mexican Revolution and the post-revolutionary policy of creating a new national identity was accompanied by the “discovery” of folk art, by urban artists and intellectuals. From the beginning of the 1920s, this form of popular expression began to influence the development of “elite art”, practiced by leading contemporary artists in Mexico. Folk art was collected, exhibited, and sold — the first major exhibition of what was called “Mexican Popular Art” took place in 1924 in Los Angeles. Broadly, this art of the everyday was (and continues to be) created by members of indigenous cultures, peasants or other artisanal tradespeople. It is rooted in traditions from particular communities and cultures, expressing shared values and aesthetics. Folk or popular art tends to be functional or decorative, rather than purely aesthetic, and uses all kinds of material — including cloth, wood, paper, clay, and metal. [caption id=“attachment_5110461” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Frida Folk, by Gaby Franger[/caption] Folk art has always been — and still is in many circles — considered more craft than art, an inferior form that does not merit serious attention. Diego Rivera put this disdain down to the arrogance of the art establishment: “The great sycophants of the arts and of art criticism talk of those works as Mexican curios, displaying with utmost clarity the dullness of their sensitivity, the falseness of their criteria, and the terror that a popular work, selling for almost nothing, is not only a threat to them, but to all vested interests and their speculators — vile rubbish and hostile to the art of the people. They are reluctant to give it at a higher rank than that of “curiosities” for tourist consumption, because if they admitted what was really there, they would have no clients, and their own production would have no purchasers, only garbage-men.” For Diego, folk art was the “true art of Mexico”. In his reflections on the work of Doña Carmen Caballero Sevilla — the creator of fantastic Judas figures (effigies of Judas Iscariot), made of papier-mâché — he basically speaks for all forms of popular artistic expression: “The true art of Mexico is called “popular”; it is created by villagers for the people, without any additions or sophistication, and it goes far beyond what school and gallery painters attempt. If a well-known painter had done what Doña Carmen did, everyone including the critics would have sung halleluiahs… proves[…] all of Carmen’s work is what the sophisticated artists would like to do, but don’t succeed in doing. Anyone who sees these creations of Doña Carmen has to realise that the really astonishing thing — apart from the feeling caused by her sensitivity to form and colour — is that of treating each example, one and the same subject — a skeleton, a death figure — absolutely differently, and the difference is nor forced or affected, but vital.” [caption id=“attachment_5110531” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Printed shoulder bag. Found in Bogotá, Columbia, 2017[/caption] Diego Rivera argues that folk forms — which are often produced in large numbers, and therefore regarded as craft souvenirs for tourists — can actually be very unique individual creations. The best of them show the skill and imagination of the creator in a manner which could be the envy of many fine artists. He and Frida had a very special relationship with the folk arts of Mexico, considering them the essence of Mexican culture. They supported a number of folk artists, and were at the forefront of the promotion of these forms among urban intellectuals and artists, who began to conceive of them “as a fundamental element of the modern nation state. Applauding the art of the people is… a necessary step toward unifying a radically diverse country.” Mexican folk art contains different worlds — the varied cultures on Mexican soil, as well as the cultures of Spain, with influences from China, Africa, and the Arab world mixed in. Diego and Frida literally surrounded themselves with Mexican popular art. They lived with and within it, as Raquel Tibol — who was at Frida’s bedside for the last time in the Blue House — describes: “Everything in the house was Mexican with a spark of art — retablos, modeled or decorated sweets, reed grass and glued paper. Judases, toys from a fair, profusely decorated furniture made of pine and fir; skeletons made of plaster, tin, cardboard, sugar and China paper that the people use to scare off gloomy thoughts on the Day of the Dead; paper cutouts; peasant dresses embroidered with an infinite variety of fretwork; floral birds and designs; cushions on which both sentimental and picaresque expressions had been embroidered with threads of all colors; candelabras, thuribles, fans, small boxes, trunks, anonymous paintings, sleeping mats, scrapes, sandals, paper and wax flowers, headdresses, wooden tattles, piñatas, masks… everything was finding its place, acquiring the grace of necessary objects, never the heaviness of useless decoration. The familiarity of one next to the other gave them unexpected power. There the past and present were joined with emphatic naturalness.” The walls of the Blue House are still packed with Exvotos, or votive offerings, referred to in Mexico as retablos. These small pictures on wooden or metal plaques chronicle accounts of miraculous healings, happy coincidences or the saving of a difficult situation — thanks to the divine omnipotence and mercy of the Virgin Mary. They are painted as offerings to her. But their charm lies equally in their ingenuous rendering of everyday life and events — the trials and tribulations of ordinary people — both real and other-worldly. [caption id=“attachment_5110541” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  T-Shirts in a street market. Found in Mexico-City, 2016[/caption] Diego considered these retablos the most genuine pictorial expression of the Mexican nation, especially of the peasant majority. Because of the miracles, every facet of their lives had been depicted. It was this traditional votive picture form that Frida picked, to paint the deepest pain that she endured after her accident: the miscarriage she suffered on 4 July 1932. In a disturbing little picture called ‘The Lost Desire’, she shows herself lying on a bed at the Henry Ford Hospital. She gives her unhappiness incredibly large scope, with this small oil painting on metal, and makes her recovery in the hospital public. The painting was shown in her exhibition of 1938: “[…] The creative characteristics of absolute sincerity and the completely direct expression in those retablos, among which are many masterworks, are the same in Frida’s paintings. Therefore anyone who considers her work as most genuinely Mexican is undoubtedly correct.” *** Frida, whose painting was steeped in Mexican folk art and imagery, has herself become part of this popular culture through its many forms of expression — constantly reinvented through and with her. It is an enduring connection which has turned out to be curiously reciprocal. Popular artists — not just in Mexico, but across a range of countries and cultures — have been inspired by her life and persona. To this day, they continue to come up with countless images and objects that evoke and reinvent Frida, keeping her alive in popular memory. Frida’s art continues to have the power to move, disturb, and thrill, even if it is endlessly replicated as a photo, or appears as an image printed on some very curious objects. The global appropriation of Frida — Fridamania — can certainly be viewed as commercialisation, trivialisation or kitsch. But is it merely that? Or is there another way to think about these creations? Could they be seen as witnesses to the times, of ever-changing lifestyles — in the best sense of the term — or things which go on to make history? All images courtesy: Tara Books

Frida Kahlo’s art continues to have the power to move, disturb, and thrill, even if it is endlessly replicated as a photo, or appears as an image printed on some very curious objects

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)