By Julia Shen Ebola’s deadly sweep across

West Africa has raised global alarm

: Nigeria recently became the fourth country affected by the virus when a traveler fell ill and died in Lagos after flying there from Monrovia. With the Nigerian case, Ebola has entered Africa’s largest economy and a global transit hub, after first emerging in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Amid escalating

travel precautions

and airline restrictions, deaths of

emergency responders

, and

headlines about national security meetings

, we’ve answered a few key questions below to put the risk in perspective. [caption id=“attachment_1654645” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Ebola affected. AFP[/caption] Is Ebola going to become pandemic? Probably not. The situation is quite serious: this is the largest and deadliest outbreak – and the first in this region – since Ebola was

first observed in 1976

. The latest

CDC notice

has officially elevated travel advisory on the three principally affected countries to “Warning Level 3, Avoid Nonessential Travel” although the

WHO has not yet echoed this call

. As Dr. Ian Mackay has depicted in his Virology Down Under infographic, these figures are equal to almost 90% of cases and 70 percent the total deaths from the first thirty years of Ebola

epidemics, combined

. Ebola has

no treatment or vaccine

, and many of its victims die after

multi-organ failure and internal and external bleeding

, leading to a fatality of 50-90 percent. Yet the biology that makes Ebola terrifying actually limits its potential as a

Hollywood-style superbug

. Ebola’s unfortunate victims suffer a few weeks of acute infection very visibly, allowing for rapid identification and containment. The virus incubates for a maximum of 21 days, contrasting sharply with HIV, which patients can have – and pass on – for years without ever showing symptoms. How does Ebola spread? Ebola is transmitted by direct contact with bodily fluids. This mode of transmission is dangerous – especially for health care workers – but much less so than a water or food pathway, as with cholera and typhoid. Unlike tuberculosis in cattle or influenza in poultry, zoonotic diseases endemic in us and our livestock that are

co-evolving with intensified agriculture

, Ebola has previously disappeared from humanity before re-emerging. Filoviridae, the virus family Ebola is a part of, seem to prefer

wild bats and apes as a host reservoir

. Contradictory to a nightmare mutation scenario,

Ebola’s genetic diversity is limited

compared to HIV or the flu, and recent experimental evidence suggests the

virus is not airborne

. A cornerstone of epidemiology is the basic reproductive number or “R0,” which describes the average number of further infections that a given sick individual will cause. Higher values mean more widespread epidemics. Ebola’s short incubation period and mode of transmission contribute to the virus’ relatively

low R0

of

1.9-2.8

in previous outbreaks. Although not precisely comparable across different mathematical models, R0 is a useful benchmark; Ebola’s is much lower than that of

measles (12.0-18.0) or polio (5.0-7.0)

.

The best published model

suggests that Ebola’s R0 falls to elimination levels – in which individuals infect So what’s the appropriate response to Ebola? Real-world complexities make R0 a moving target. It is conceivable that Ebola will spread farther, including to pockets outside Africa. Recent incidence is worrying, especially in Sierra Leone. Nearly 900 people have died in the eight months

since the current outbreak started in rural Guinea

. This visceral danger sells papers. But

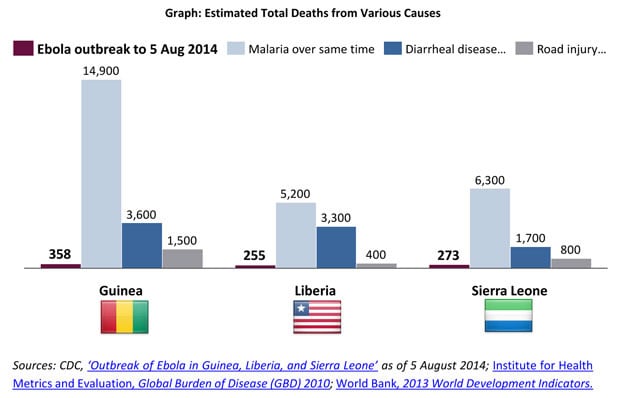

everyday diarrheal disease

killed almost the same number of people in the West African sub-region today alone; malaria killed even more in the same 24 hours. In terms of absolute risk in the affected countries, road injuries still exceed Ebola.

Ebola affected. AFP[/caption] Is Ebola going to become pandemic? Probably not. The situation is quite serious: this is the largest and deadliest outbreak – and the first in this region – since Ebola was

first observed in 1976

. The latest

CDC notice

has officially elevated travel advisory on the three principally affected countries to “Warning Level 3, Avoid Nonessential Travel” although the

WHO has not yet echoed this call

. As Dr. Ian Mackay has depicted in his Virology Down Under infographic, these figures are equal to almost 90% of cases and 70 percent the total deaths from the first thirty years of Ebola

epidemics, combined

. Ebola has

no treatment or vaccine

, and many of its victims die after

multi-organ failure and internal and external bleeding

, leading to a fatality of 50-90 percent. Yet the biology that makes Ebola terrifying actually limits its potential as a

Hollywood-style superbug

. Ebola’s unfortunate victims suffer a few weeks of acute infection very visibly, allowing for rapid identification and containment. The virus incubates for a maximum of 21 days, contrasting sharply with HIV, which patients can have – and pass on – for years without ever showing symptoms. How does Ebola spread? Ebola is transmitted by direct contact with bodily fluids. This mode of transmission is dangerous – especially for health care workers – but much less so than a water or food pathway, as with cholera and typhoid. Unlike tuberculosis in cattle or influenza in poultry, zoonotic diseases endemic in us and our livestock that are

co-evolving with intensified agriculture

, Ebola has previously disappeared from humanity before re-emerging. Filoviridae, the virus family Ebola is a part of, seem to prefer

wild bats and apes as a host reservoir

. Contradictory to a nightmare mutation scenario,

Ebola’s genetic diversity is limited

compared to HIV or the flu, and recent experimental evidence suggests the

virus is not airborne

. A cornerstone of epidemiology is the basic reproductive number or “R0,” which describes the average number of further infections that a given sick individual will cause. Higher values mean more widespread epidemics. Ebola’s short incubation period and mode of transmission contribute to the virus’ relatively

low R0

of

1.9-2.8

in previous outbreaks. Although not precisely comparable across different mathematical models, R0 is a useful benchmark; Ebola’s is much lower than that of

measles (12.0-18.0) or polio (5.0-7.0)

.

The best published model

suggests that Ebola’s R0 falls to elimination levels – in which individuals infect So what’s the appropriate response to Ebola? Real-world complexities make R0 a moving target. It is conceivable that Ebola will spread farther, including to pockets outside Africa. Recent incidence is worrying, especially in Sierra Leone. Nearly 900 people have died in the eight months

since the current outbreak started in rural Guinea

. This visceral danger sells papers. But

everyday diarrheal disease

killed almost the same number of people in the West African sub-region today alone; malaria killed even more in the same 24 hours. In terms of absolute risk in the affected countries, road injuries still exceed Ebola.

The root causes of mortality from malaria and diarrheal disease also accelerate the spread of Ebola. Post-conflict Liberia and Sierra Leone are among the poorest countries in the world. Despite their natural resource wealth,

Guinea

and

Nigeria

have under-resourced health sectors, below the African Union’s

2001 Abuja Declaration health targets

. Only

$67 – $205

is spent annually per person on health in these four countries affected by Ebola. A distrust of medicine and lack of health education are

worsening the outbreak

– infected patients sometimes even

flee treatment wards

. But suspicion of health services is more understandable in a context where clinics are usually

short of qualified staff

(Liberia has all of ~60 doctors),

drugs regularly stock out

, and

life expectancy may only be 45 years

. In an age of air travel and worldwide trade, closed borders are simply not a sustainable solution to preventing the spread of diseases such as Ebola: it is not a matter of if, but when, the next disease emerges, potentially as a more dangerous respiratory illness. While more infectious risk is inevitable for a growing human population, however, the

histories of smallpox and polio

show that massive death and suffering are preventable. The current Ebola outbreak is not an occasion for panic but should raise an urgent call for

public health investment in West Africa

and other underserved regions, for our

shared global health security

. Leadership from national authorities and international partners can curb the economic damages and public anxiety, ending the loss of life from Ebola – and the longstanding pandemics already affecting hundreds of millions of people every day. The author is a consultant in

Dalberg Global Development Advisors

’ Dakar office. This article was reviewed by Dr. Manpreet Singh (MB BChir MPH), also a consultant in Dalberg’s Nairobi office. Dalberg is a strategy and policy advisory firm dedicated to global development. This piece first appeared on Dalberg’s blog on 5 August 2014.

The root causes of mortality from malaria and diarrheal disease also accelerate the spread of Ebola. Post-conflict Liberia and Sierra Leone are among the poorest countries in the world. Despite their natural resource wealth,

Guinea

and

Nigeria

have under-resourced health sectors, below the African Union’s

2001 Abuja Declaration health targets

. Only

$67 – $205

is spent annually per person on health in these four countries affected by Ebola. A distrust of medicine and lack of health education are

worsening the outbreak

– infected patients sometimes even

flee treatment wards

. But suspicion of health services is more understandable in a context where clinics are usually

short of qualified staff

(Liberia has all of ~60 doctors),

drugs regularly stock out

, and

life expectancy may only be 45 years

. In an age of air travel and worldwide trade, closed borders are simply not a sustainable solution to preventing the spread of diseases such as Ebola: it is not a matter of if, but when, the next disease emerges, potentially as a more dangerous respiratory illness. While more infectious risk is inevitable for a growing human population, however, the

histories of smallpox and polio

show that massive death and suffering are preventable. The current Ebola outbreak is not an occasion for panic but should raise an urgent call for

public health investment in West Africa

and other underserved regions, for our

shared global health security

. Leadership from national authorities and international partners can curb the economic damages and public anxiety, ending the loss of life from Ebola – and the longstanding pandemics already affecting hundreds of millions of people every day. The author is a consultant in

Dalberg Global Development Advisors

’ Dakar office. This article was reviewed by Dr. Manpreet Singh (MB BChir MPH), also a consultant in Dalberg’s Nairobi office. Dalberg is a strategy and policy advisory firm dedicated to global development. This piece first appeared on Dalberg’s blog on 5 August 2014.

Ebola explained: What is the real risk of the W. African outbreak?

FP Archives

• August 8, 2014, 12:48:45 IST

In an age of air travel and worldwide trade, closed borders are simply not a sustainable solution to preventing the spread of diseases such as Ebola

Advertisement

)