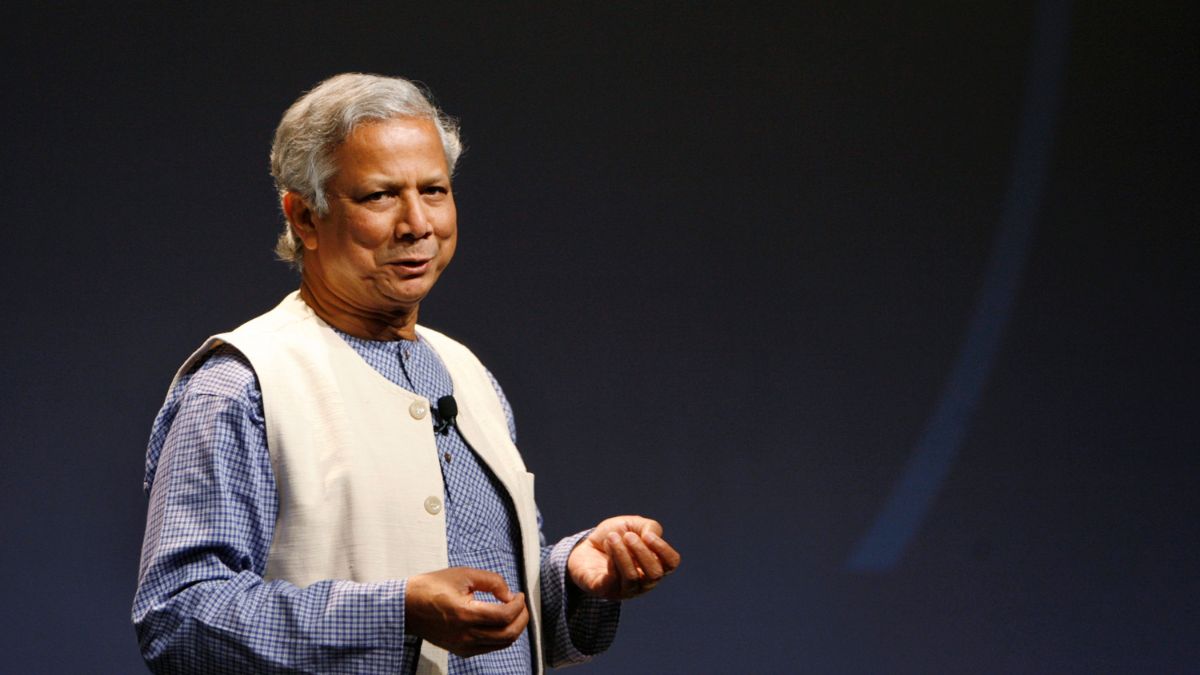

Muhammad Yunus , the Nobel laureate and founder of Grameen Bank, once hailed as the saviour of Bangladesh’s poor, is now at the centre of an international geopolitical game. Appointed as the chief adviser to Bangladesh’s interim government following Sheikh Hasina’s dramatic exit in August 2024, Yunus has since transformed from a globally celebrated development icon into a power-hungry technocrat.

As the chief adviser, Yunus is practically the head of the Bangladesh government with powers comparable to the prime minister, though theoretically curtailed. Constitutionally, Yunus’s primary responsibility is to hold parliamentary election in Bangladesh, paving way for the return of an elected government. But Yunus has shown no intention of relinquishing control of power.

His statements indicate that Yunus is not inclined to hold parliamentary election in Bangladesh anytime soon. He has dropped hints that it could be held in 2026. He is using this time to undertake key bilateral visits to Pakistan and China, two countries profusely interested in geopolitical gains in Bangladesh, a country that sits on the top of key Bay of Bengal basin.

Incidentally, China and Pakistan have emerged as Yunus ’s most ardent supporters. Both these countries are not known for their democratic credentials. Their reasons are both strategic and ideological. Both nations see Yunus’s prolonged hold on power and the indefinite delay of elections as beneficial to their respective regional ambitions—particularly to counter India’s influence, propagate authoritarian governance and bolster Islamist political elements in Bangladesh.

China’s long game in South Asia

For China, Bangladesh is a crucial link in its South Asian strategy. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has already seen significant investments in Bangladeshi infrastructure, including ports, railways and power plants. A democratic government might reassess or renegotiate these projects, especially if nationalist sentiment rises. Yunus, leading a technocratic interim government with no direct electoral accountability provides Beijing the perfect insurance policy.

For the communist regime of Beijing, Yunus — untethered from electoral mandates — is someone who can offer practically no “resistance to long-term strategic projects like China’s Belt and Road Initiative". With Yunus delaying elections under the pretext of electoral reforms, China can rest easy knowing that its investments are secure, at least for the foreseeable future.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsMoreover, China has consistently opposed the spread of democratic activism along its borders. To suit the Chinese design, Yunus recently floated a tentative election timeline extending into 2026 citing the need for “national consensus” and “electoral reform”. Both these processes can be an endless wait for a country trained in democracy. For Beijing, such rhetoric mimics its own authoritarian governance model, which cloaks centralised control in technocratic or reformist language.

What’s in it for Pakistan

Pakistan’s interest in Yunus staying in power is less about infrastructure and more about ideology, regional power play and strategic depth in raising fundamentalist elements that can be used against India. Under Hasina, Bangladesh had strengthened its ties with India, particularly in counterterrorism and economic cooperation. Hasina’s administration aggressively cracked down on Islamist extremists and kept Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in check.

With Hasina gone, Islamabad sees a rare opportunity. Experts point out Pakistan’s ISI has worked in tandem with various Islamist factions and even aligned itself with elements of the US “deep state” to facilitate Hasina’s ouster. Now, with Yunus at the helm, Pakistan is eager to tilt Dhaka’s policies more toward Islamabad and away from New Delhi.

This effort includes encouraging Bangladesh to adopt a more favourable stance on issues like Jammu and Kashmir and playing down India’s role in the 1971 Liberation War. Notably, on the 54th Vijay Diwas (16 December), Yunus made no mention of India’s role or Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s leadership, choosing instead to slam Hasina’s government as the “world’s worst autocratic regime”. This calculated omission speaks volumes and aligns with Pakistan’s revisionist narrative.

There is another reason for Pakistan to keep a pliable ’not India-friendly’ person as the Bangladesh leader. India has called Pakistan’s bluff with Operation Sindoor after the Pahalgam terror attack in Jammu and Kashmir on April 22. India has concretised its counter-terror policy by announcing that any act of terror by Pakistan or outfits it has sheltered and and patronised for years as an act of war and will be responded accordingly without making a distinction between the state and non-state actors hetherto maintained in New Delhi’s response.

If Pakistan’s terror policy, “to bleed India by a thousand cuts”, gets operational from the soil of Bangladesh, it might create a new dilemma for New Delhi. Terrorism observers say Pakistan has used a similar approach in the past, when outfits such as Harkat-ul-Jihad-al Islami (HuJI) carried out terror blasts in India.

Islamic radicalism and Jamaat-e-Islami

There is a reason for concern in the security establishment of India and other parts of the world. Bangladesh observers say that the most troubling development under the Yunus-led interim government has been the resurgence of Islamist groups — particularly Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) — in Bangladeshi politics. JeI had been marginalised and proscribed under the Hasina government, but the interim government lifted the ban, and has shown great tolerance (if not outright support) for their return to political contests. This signals a dangerous ideological shift.

Yunus has shown the political resolve to tackle these radical elements as they make a comeback in the post-Hasina vacuum. Banned terrorist groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir have begun operating openly again and extremist clerics like Mufti Jashimuddin Rahmani, affiliated with Ansarullah Bangla Team (an Al Qaeda-inspired outfit), have been released. This suggests that the interim government is either unwilling or unable to contain radical forces.

Firstpost earlier reported how Yunus’s administration has shown leniency toward extremists while simultaneously cracking down on minority voices. These moves reflect a judiciary increasingly biased toward Islamist narratives and against secular, democratic dissent.

Jamaat’s deepening influence

JeI’s influence is not limited to street-level radicalism. It has infiltrated state mechanisms under the Yunus administration. The Firstpost report showed how Jamaat’s student wing, Islamic Chhatra Shibir (ICS), played a key role in the student agitation that led to Hasina’s removal. They were also reportedly involved in attacks on minority people after Hasina fled to New Delhi for her life. These groups are not just foot soldiers; they are ideologically motivated operatives linked to the Muslim Brotherhood and similar Islamist movements in Turkey, Egypt and the Gulf states.

The growing political clout of JeI is viewed by many as a stepping stone toward dismantling Bangladesh’s parliamentary democracy in favour of an Islamic theocracy. Political observers cited warn that the constitutional reforms proposed under Yunus may serve precisely this goal. The Yunus-led government has formed committees to rewrite Bangladesh’s legal and governance frameworks—without any electoral mandate. Critics see this as a calculated move to institutionalise religious conservatism.

This ideological pivot serves both Pakistan and segments of the Islamist world who see Bangladesh as fertile ground for reviving political Islam. Yunus, despite his global persona as a peace-promoting economist, is increasingly being seen as a puppet of JeI and its foreign backers.

BNP senses betrayal in Bangladesh’s democratic transition

As reported by The Daily Star, senior Bangladesh National Party (BNP) leader Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir expressed concerns on Tuesday that a deliberate and coordinated effort appears to be unfolding to indefinitely postpone the national elections and deny citizens their fundamental democratic rights.

He reflected on the sacrifices made by countless students and civilians in the struggle for democracy, stating that despite those efforts creating a window for positive change, the political atmosphere remains ominous and uncertain.

Within the BNP, growing scepticism surrounds Yunus’s intentions regarding the restoration of electoral democracy. Once optimistic about reclaiming power following the fall of the Awami League, the party now feels increasingly marginalised in the evolving political scenario.

Meanwhile, a growing rift is emerging within Bangladesh’s interim leadership, with tensions reportedly surfacing between Yunus and Army Chief General Waker-Uz-Zaman.

According to a report by News18, General Zaman is said to be advocating for swift national elections to restore democratic governance. In contrast, Yunus seems intent on postponing the electoral process, allegedly aligning himself with factions opposed to Zaman—many of whom are seen as having close ties to foreign governments.

Lessons from China and Pakistan

Authoritarian regimes have a vested interest in supporting or tolerating similar regimes in neighbouring countries. Beijing and Islamabad both perceive democratic activism and electoral accountability as existential threats. Yunus’s continued delay of elections under the guise of reform and national consensus echoes methods used by authoritarian leaders elsewhere to consolidate power.

Authoritarian governments prefer technocratic regimes that can sideline messy democratic processes. A caretaker government that indefinitely postpones elections is more predictable, easier to negotiate with and less subject to public pressure. Yunus’s narrative of needing time for reforms, national consensus and electoral restructuring is a tried-and-true formula for indefinite power retention.

Beijing and Islamabad may not have identical reasons for wanting Yunus in power, but they converge on one point: the need to suppress democratic momentum in a region increasingly influenced by India’s democratic model.

India’s strategic dilemma

India, Bangladesh’s largest neighbour, has also been it longtime ally. But with an elected government toppled, and India-friendly voices sidelined by the Yunus-led government, New Delhi is waiting for a government with popular mandate in Dhaka to redefine bilateral ties. The power vacuum created by Hasina’s exit has been quickly filled by forces antithetical to India’s regional vision and they seem to be looking at causing a permanent trust deficit with Bangladesh’s strongest ally.

By minimising India’s involvement in the events of 1971, the current leadership is signalling a departure from longstanding historical accounts. This move is part of a calculated push to redefine national identity and steer the country in a new political direction.

The exit of Hasina also saw a concerted effort by external powers, reportedly coordinated through Pakistan’s ISI, to undermine India’s influence in Bangladesh. India, on its part, has called for early elections and refrained from according a permanent legitimacy to a temporary power arrangement in Yunus’s office.

This reorientation is not just symbolic. If Bangladesh aligns more closely with Pakistan and China, it may alter the strategic balance in South Asia. A radicalised, authoritarian Bangladesh could serve, in theory, as a base for anti-India activities and even act as a corridor for Chinese influence reaching into the Bay of Bengal. There are, of course, practical and geographical challenges, which Yunus has alluded to in his remarks on India’s Northeastern states, drawing sharp flak from New Delhi.

Yunus’s interim leadership in Bangladesh, at the same time, looks to mark more than just a temporary change in power. Behind the scenes, it reflects a strategic intervention by China and Pakistan to reshape the balance of power in South Asia. Their support for Yunus is not incidental—it serves a broader goal of undermining India’s regional standing.

By elevating a technocrat with connections to Islamist factions, they may quietly be embedding ideological allies in Dhaka’s power structure. The continued delay in holding parliamentary election, framed as a reform effort, is effectively a tool to entrench this new order.

Yunus, once hailed globally for his work in microfinance, has now become a convenient figurehead for external interests. As he looks to tighten his grip with minimal internal resistance and declining global scrutiny, democratic space in Bangladesh continues to shrink.

For India, and for proponents of democratic norms, the implications could be significant. Some say India should be more aggressive in countering this shift instead of waiting for an elected government to come back in Dhaka. Recent punitive economic and commercial measures announced by India do signal a shift in approach.

)