Brunei, officially Brunei Darussalam, sits on the Borneo island bordered by Malaysia and just outside the South China Sea, claimed largely by China as its sovereign territory. Brunei has about 160-km coastline in the oil-gas rich sea, putting it in direct conflict with China amid Beijing increasing military assertiveness in the region.

Brunei and Beijing have a long history of bilateral ties, going back some 2,000 years, when the Han dynasty ruled China. During the rule of the Ming dynasty in China, the tomb of Brunei Sultan Abdul Majid Hassan was constructed in Nanjing in the 15th century.

With a history of warm ties, Brunei-China relations underwent an eclipsing change as Brunei came under British protectorate, following which the emergence of the Chinese Communist Party as the ruling power in China has defined the bilateral relationship.

Brunei and communist China established official diplomatic relations in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union and the consequent end of the Cold War. Their bilateral relations explained in 10 points below:

Brunei and China have routinely exchanged high-level visits since establishing diplomatic relations, especially around Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summits. Haji Hassanal Bolkiah, Brunei’s sultan since 1967, became the first Bruneian head of state to visit China — at least 10 tours, including state visits in 2013 and 2017.

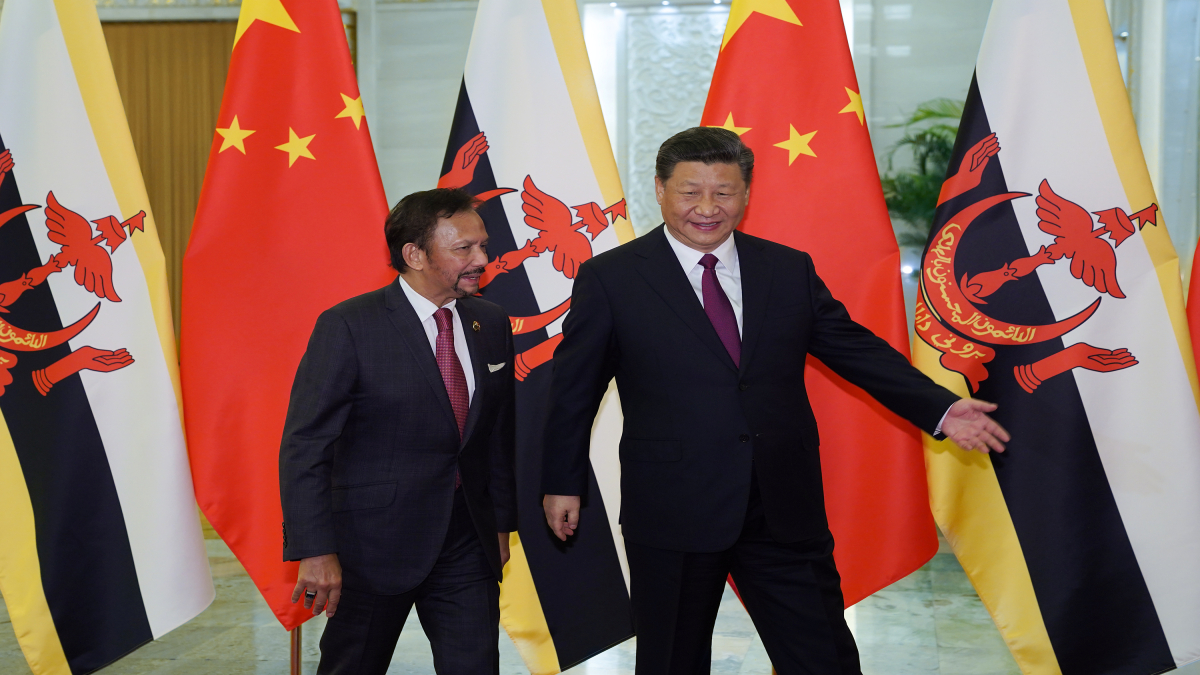

Jiang Zemin was the first Chinese head of state to visit Brunei in 2000, followed by Hu Jintao in 2005. China’s President Xi Jinping visited Brunei in 2018 — his first — and both countries agreed to elevate their ties to strategic cooperation partnership.

Going by the trade and China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, it appears that China-Brunei relations are quite strong. However, disputes over South China Sea claims are big spoilers. Brunei has been the quietest claimant nation, bordering on complete silence and the territorial and maritime boundary dispute has scarcely been an issue, says US Institute of Peace.

China has pressed Brunei delicately for a joint development agreement, but Brunei has thus far resisted. Overall, the China-Brunei dispute in the South China Sea has two key facets. Dispute over maritime boundary lines is the first concern.

China defines its boundary in the South China Sea through a so-called nine-dash line — which has become the 10-dash line in recent years. The fifth and sixth dashes of China’s maritime boundary line takes Beijing’s sovereign claim to within 35 nautical miles of Brunei’s coast, where a majority of its vital offshore energy industry is located.

Brunei’s problem seems to be its dilemma about going open with its dispute with China and rejecting the nine-dash line publicly. The monarchy has not rejected the nine-dash line or declared it incompatible with the 1982 UN treaty governing seas and oceans — the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), something that the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia have done.

But then, Brunei has a clean track-record in adhering to the UNCLOS, which makes its maritime jurisdictional claim on the South China Sea areas indisputable, especially against the background China’s repeated violations. Already, a UN-backed arbitral tribunal has rejected China’s maritime jurisdictional claims with a July 2016 ruling.

The second major concern of the China-Brunei dispute is about the character of the maritime region. The Louisa Reef (a low-tide elevation) and the Riflemen Bank (a submerged feature) are the major geographical features that are located within Brunei’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) — a UN-approved legality that allows a nation to claim territorial rights up to 12 nautical miles and exclusive economic right up to 200 nautical miles.

But the problem is that under Chinese pressure, Brunei has never formally claimed Louisa Reef and Rifleman Bank. However, its official position appears to include Rifleman Bank as part of its extended continental shelf.

These two islands are part of the Spratly Islands, contested between China and Vietnam as well. In a different settlement in 2019, Malaysia relinquished its claim to Louisa Reef in exchange for Brunei abandoning its territorial claim to Limbang in Sarawak. But both Malaysia and Brunei, which aim to jointly develop maritime resources in the latter’s exclusive economic zone, feel the pressure from China’s growing assertions.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)