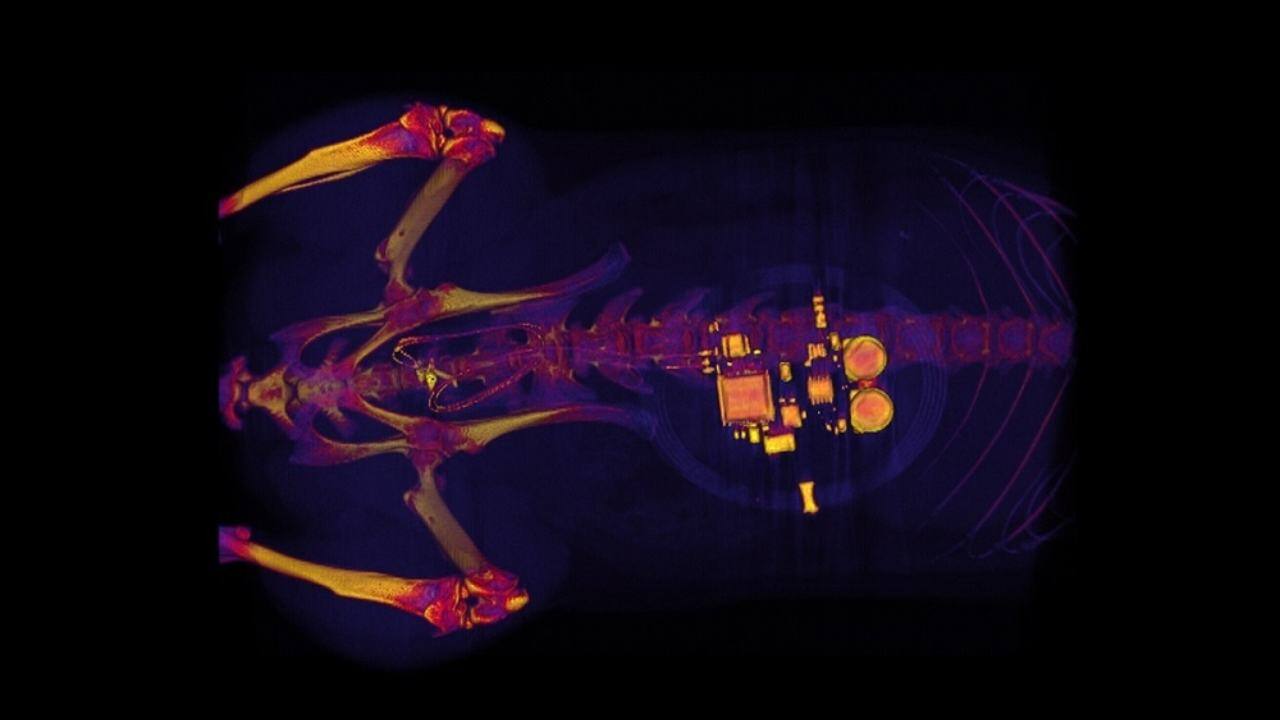

A new implant developed by a team of neuroscientists and engineers at Washington University in St Louis can treat troubled bladders using an unlikely tool: Light! The team has created a soft device that can be implanted into animals (maybe people, too, someday) that can pick up on an overactive bladder and use light from a tiny, bio-integrated LED to reduce the animal’s urge to take frequent leaks. How does the device work? The implantable device uses Bluetooth connectivity to signal to an external handheld device when it detects a full bladder, when the bladder has been emptied, or when the animal seems to make an unusually high number of bathroom runs — all using a simple algorithm. [caption id=“attachment_5833911” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] This CT scan of a rat shows a small device implanted around the bladder that uses light signals from tiny LEDs to activate nerve cells in the bladder and control problems such as incontinence and overactive bladder. Image credit: Gereau Lab/Washington University[/caption] “When the bladder is emptying too often, the external device sends a signal that activates micro-LEDs on the bladder band device, and the lights then shine on sensory neurons in the bladder. This reduces the activity of the sensory neurons and restores normal bladder function,” Robert W Gereau, one of the study’s senior investigator said in

a statement

. “We’re excited about these results. This example brings together the key elements of an autonomous, implantable system that can operate in synchrony with the body to improve health: a precise sensor of organ activity, a noninvasive means to modulate that activity, a soft, battery-free module for wireless communication and control, and data analytics algorithms for closed-loop operation,” John A Rogers, the study’s other senior investigator, added. Closed-loop operations essentially mean that the device delivers a therapy only when it detects a problem. When the behaviour returns to normal again, the micro-LEDs turn off and the treatment is discontinued. [caption id=“attachment_5833981” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”]

This CT scan of a rat shows a small device implanted around the bladder that uses light signals from tiny LEDs to activate nerve cells in the bladder and control problems such as incontinence and overactive bladder. Image credit: Gereau Lab/Washington University[/caption] “When the bladder is emptying too often, the external device sends a signal that activates micro-LEDs on the bladder band device, and the lights then shine on sensory neurons in the bladder. This reduces the activity of the sensory neurons and restores normal bladder function,” Robert W Gereau, one of the study’s senior investigator said in

a statement

. “We’re excited about these results. This example brings together the key elements of an autonomous, implantable system that can operate in synchrony with the body to improve health: a precise sensor of organ activity, a noninvasive means to modulate that activity, a soft, battery-free module for wireless communication and control, and data analytics algorithms for closed-loop operation,” John A Rogers, the study’s other senior investigator, added. Closed-loop operations essentially mean that the device delivers a therapy only when it detects a problem. When the behaviour returns to normal again, the micro-LEDs turn off and the treatment is discontinued. [caption id=“attachment_5833981” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] Urinary incontinence is far from just an old-people-problem.[/caption] What’s next? The team also thinks that the approach used in their model could be applied to other treatments, like chronic pain or stimulating pancreatic cells to secrete insulin. That said, one potential drawback of their approach is the use of viruses to bind light-sensitive proteins to cells in organs. “We don’t yet know whether we can achieve stable expression of the opsins using the viral approach and — more importantly — whether this will be safe over the long term. That issue needs to be tested in preclinical models and early clinical trials to make sure the strategy is completely safe,” Gereau said.

Urinary incontinence is far from just an old-people-problem.[/caption] What’s next? The team also thinks that the approach used in their model could be applied to other treatments, like chronic pain or stimulating pancreatic cells to secrete insulin. That said, one potential drawback of their approach is the use of viruses to bind light-sensitive proteins to cells in organs. “We don’t yet know whether we can achieve stable expression of the opsins using the viral approach and — more importantly — whether this will be safe over the long term. That issue needs to be tested in preclinical models and early clinical trials to make sure the strategy is completely safe,” Gereau said.

Tiny implantable device uses light to monitor, potentially treat bladder problems

tech2 News Staff

• January 4, 2019, 10:34:11 IST

The device also uses bluetooth to alert an external handheld device when it detects bladder problems.

Advertisement

)

End of Article