Dusk has set on Dawn — NASA’s pioneering mission to study objects in the asteroid belt. After its 11-year lifetime, the spacecraft has “run out of fuel and died”, NASA announced in

a release on 1 November. Dawn is the second NASA mission which had to be retired this week. The Kepler mission, primed to search for potentially habitable planets in our galaxy, also ran out of fuel, an

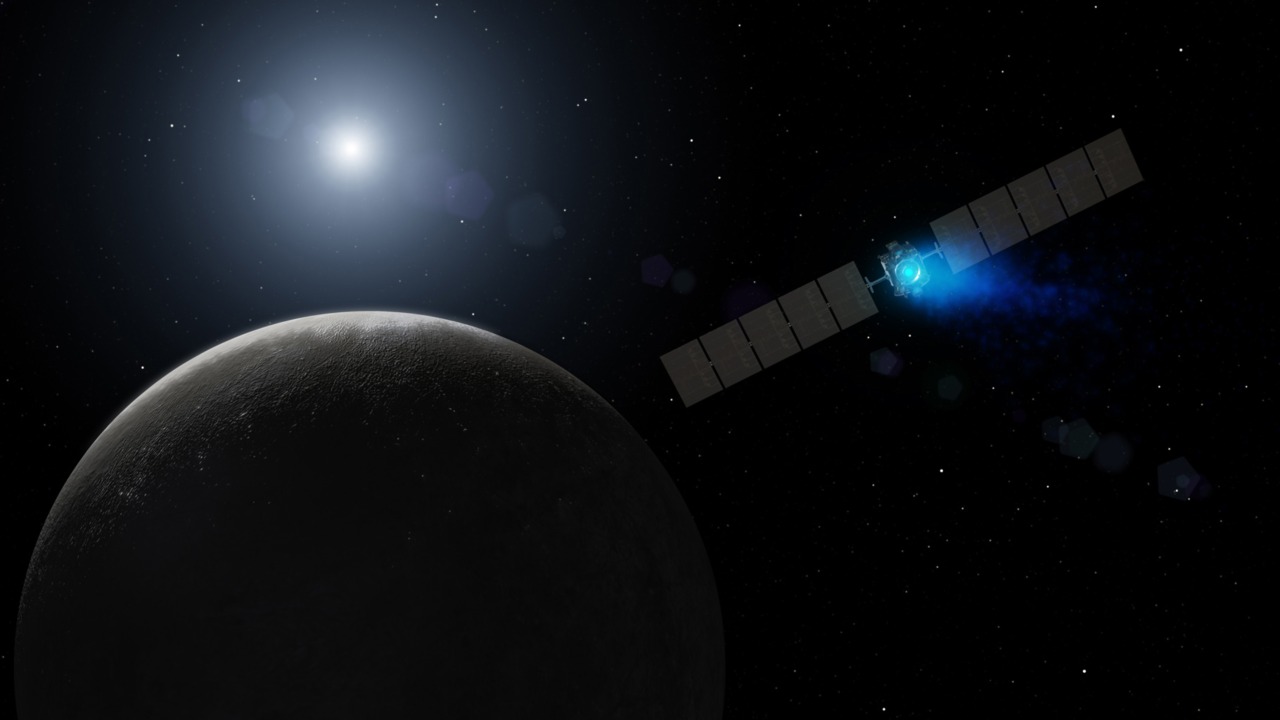

**announcement** on 30 October said. Dawn was particularly interesting to space fans for bringing science fiction to life with a working ion propulsion system. The spacecraft used ion propulsion to muster the velocity it needed to reach the asteroid belt from the Delta launch rocket. This futuristic, hyper-efficient propulsion system was a first for any spacecraft in 2007 when Dawn was launched. [caption id=“attachment_5492441” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] An artist’s concept of NASA Dawn. Image courtesy: NASA[/caption] Dawn surveyed two of the largest asteroids in the main asteroid belt — Ceres and Vesta. Both these objects were studied as likely ‘protoplanets’ — large orbiting rocks thought to be gradually forming a planet. “The demands we put on Dawn were tremendous, but it met the challenge every time,” Marc Rayman, Dawn’s mission director and chief engineer, said in

a statement. Over its 14-month survey of Vesta, Dawn discovered liquid water once flowed on the protoplanet’s surface, and that the protoplanet sports a mountain as tall as Mars’s famous Olympus Mons. The spacecraft arrived on Ceres in 2015, making it the first spacecraft to orbit a dwarf planet and the first to orbit two celestial bodies apart from the Earth and Moon.

“Dawn’s data sets will be deeply mined by scientists working on how planets grow and differentiate, and when and where life could have formed in our solar system,” Carol Raymond, principal investigator of the Dawn mission, said in the same statement. The Dawn mission team found that the spacecraft was out of hydrazine fuel after it missed a routine check-in with NASA’s Deep Space Network satellites on 31 October and 1 November. Since hydrazine powers Dawn’s thrusters, it can no longer point itself in orientations to study Ceres, relay information back to Earth or charge its solar panels. This leaves Dawn to continue orbiting Ceres for a minimum of 20 years, possibly longer. The team said there’s a “more than 99 percent probability” that the spacecraft won’t spiral down towards Ceres and fall into its cold, rough terrain for at least five decades.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)