With both air and ocean temperatures on the rise, thawing Arctic ice is a major concern for researchers. 70 percent of infrastructure in the Arctic region is at risk, including important oil and gas reserves underneath, a new study reports. The data collected on damage to infrastructure came from incidents that are affecting those living in the Northern Hemisphere already: shaky buildings, cracked roads, railways and other construction that isn’t equipped to adapt to our changing climate. Permafrost is a mix of solid ice and soil that has been frozen for two or more years, and not necessarily permanently. The majority of Earth’s permafrost is tucked away in the Northern Hemisphere, where it covers over a quarter of the exposed land. Much of the permafrost in this region is thousands of years old. It covers a wide belt between the Arctic Circle and boreal forests that span Alaska, Canada, northern Europe and Russia.

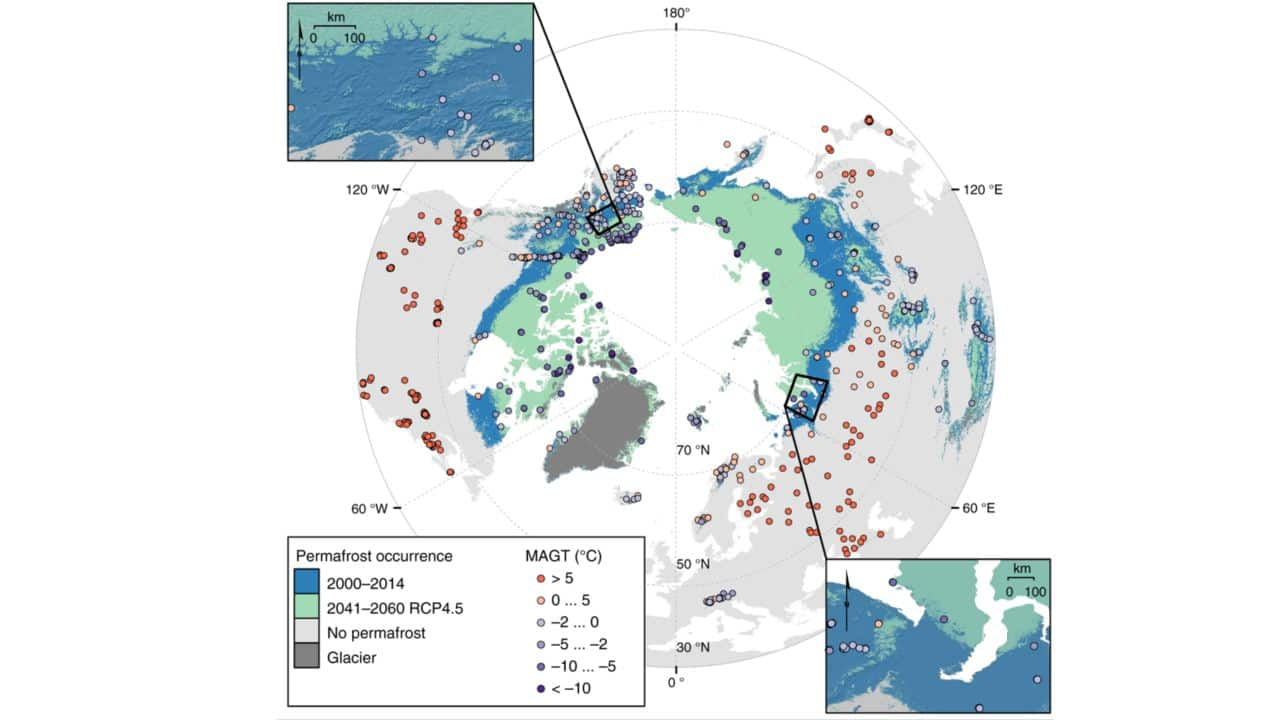

Permafrost is also found (though, to a lesser degree) in the Southern Hemisphere, where there is less ground to freeze — the South American Andes and Antarctica. Researchers used detailed information on infrastructure in the Northern Hemisphere’s permafrost zone to map just how many such structures could be at risk by the year 2050. The map shows in unprecedented detail the changes over time and temperature we can expect from the leaving the Arctic permafrost to thaw unattended. “The magnitude of the threat was in a way surprising,” Dr Jan Hjort, lead author and professor of physical geography at Finland’s University of Oulu,

told

AFP. “Especially that around 70 percent of current infrastructure in the permafrost domain is in areas with high potential for thaw of near-surface permafrost.” “By 2050, 3.6 million people… may be affected by damage to infrastructure affected by permafrost thaw,” the study,

published in

Nature Communications, reads. The study also warns that nearly half the important and hotly-contested oil and natural gas fields in the Arctic are in areas with “high hazard potential” of thawing by the year 2050. Even if global leaders can keep to the promises made in the Paris climate accord, infrastructure risks up to 2050 will remain the same, the study says. Keeping the temperature rise since pre-industrial levels below 2C is likely to reduce the devastation to come beyond 2050, the study adds. [caption id=“attachment_5714651” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] A map of thawing artic permafrost over temperature and time. Image courtesy: Nature[/caption] “Maybe these results can be taken as ‘wake-up calls,’” Hjort said, calling for more efforts to carry out risk assessments at a local scale. This, according to Hjort, will give better insight into the scale and range of damage that permafrost thaw can really cause. In all, around 65 percent of Russia territory is covered by permafrost, and the country is already fighting the impacts of thawing. In the Siberian city of Yakutsk, buildings have started to sag and crack as the ground literally shifts underneath. Researchers are experimenting with different means to keep the ground frozen as the atmosphere warms. But the study warns that “their economic cost may be prohibitive” to implement in patches of a country as opposed to an entire continent. This year, Yakutia — where Yakutsk is located — also passed a permafrost protection law, and is lobbying Moscow to take measures on a national level. The law calls for the monitoring and prevention of irreversible loss of permafrost. The study also urges that further work be done to understand what infrastructure in affected regions is most vulnerable, so that targeted action can be taken to protect and reverse the effects of thawing as best as possible.

A map of thawing artic permafrost over temperature and time. Image courtesy: Nature[/caption] “Maybe these results can be taken as ‘wake-up calls,’” Hjort said, calling for more efforts to carry out risk assessments at a local scale. This, according to Hjort, will give better insight into the scale and range of damage that permafrost thaw can really cause. In all, around 65 percent of Russia territory is covered by permafrost, and the country is already fighting the impacts of thawing. In the Siberian city of Yakutsk, buildings have started to sag and crack as the ground literally shifts underneath. Researchers are experimenting with different means to keep the ground frozen as the atmosphere warms. But the study warns that “their economic cost may be prohibitive” to implement in patches of a country as opposed to an entire continent. This year, Yakutia — where Yakutsk is located — also passed a permafrost protection law, and is lobbying Moscow to take measures on a national level. The law calls for the monitoring and prevention of irreversible loss of permafrost. The study also urges that further work be done to understand what infrastructure in affected regions is most vulnerable, so that targeted action can be taken to protect and reverse the effects of thawing as best as possible.

)