Last year, a Chinese researcher stunned the world by announcing his joy and success with editing human genes in tiny human embryos. The objective of this research is to give the human babies resistance to HIV, which received massive criticism from the research community since there are far safer and more effective ways to do that than an unapproved gene editing experiment.

A scientist in New York appears to be working on something very similar – modifying humans embryos to prevent the child from getting inherited or genetic diseases, according to an NPR

report

. While the Columbia University scientist, Dr Dieter Egli, isn’t creating any genetically-modified babies or implanting these gene-edited embryos into mothers, he admits that the ultimate goal of his future research is probably just that. Egli is a developmental biologist currently working on genetically-modified embryos “for research purposes only.” He wants to find our whether CRISPR gene editing technology is a safe way to repair mutations in embryos. Such mutations would otherwise manifest as a genetic or congenital disorder and be inherited by all the generations that follow. [caption id=“attachment_6029121” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] Dieter Egli at work. Image credit: Rob Stein/NPR[/caption] So far, the longest Egli claims to have allowed a genetically-modified embryo to live is one day. “Right now we are not trying to make babies. None of these cells will go into the womb of a person,” he says. Egli’s research is focussed on fixing a genetic defect called retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited form of blindness, in embryos. If it works, people with the genetic illness would be able to have biological children of their own with normal eyesight. Unlike He Jiankui’s study in China, Egli’s research is overseen by a panel of scientists and bioethicists at Columbia in advance of his experiments. Still, experts have expressed concerns and criticism for the basic research that Egli and his team are working on. [caption id=“attachment_5624551” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”]

Dieter Egli at work. Image credit: Rob Stein/NPR[/caption] So far, the longest Egli claims to have allowed a genetically-modified embryo to live is one day. “Right now we are not trying to make babies. None of these cells will go into the womb of a person,” he says. Egli’s research is focussed on fixing a genetic defect called retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited form of blindness, in embryos. If it works, people with the genetic illness would be able to have biological children of their own with normal eyesight. Unlike He Jiankui’s study in China, Egli’s research is overseen by a panel of scientists and bioethicists at Columbia in advance of his experiments. Still, experts have expressed concerns and criticism for the basic research that Egli and his team are working on. [caption id=“attachment_5624551” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] He Jiankui during an interview at his laboratory in Shenzhen in China. AP[/caption] “If we’ve learned anything from what’s happened in China, it’s that the urge to race ahead pushes science to shoot first and ask questions later,” J Benjamin Hurlbut, an associate professor of biology and society at Arizona State University,

told

NPR

. “But this is a domain where we should be asking questions first. And maybe never shooting. What’s the rush?” [caption id=“attachment_5624541” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”]

He Jiankui during an interview at his laboratory in Shenzhen in China. AP[/caption] “If we’ve learned anything from what’s happened in China, it’s that the urge to race ahead pushes science to shoot first and ask questions later,” J Benjamin Hurlbut, an associate professor of biology and society at Arizona State University,

told

NPR

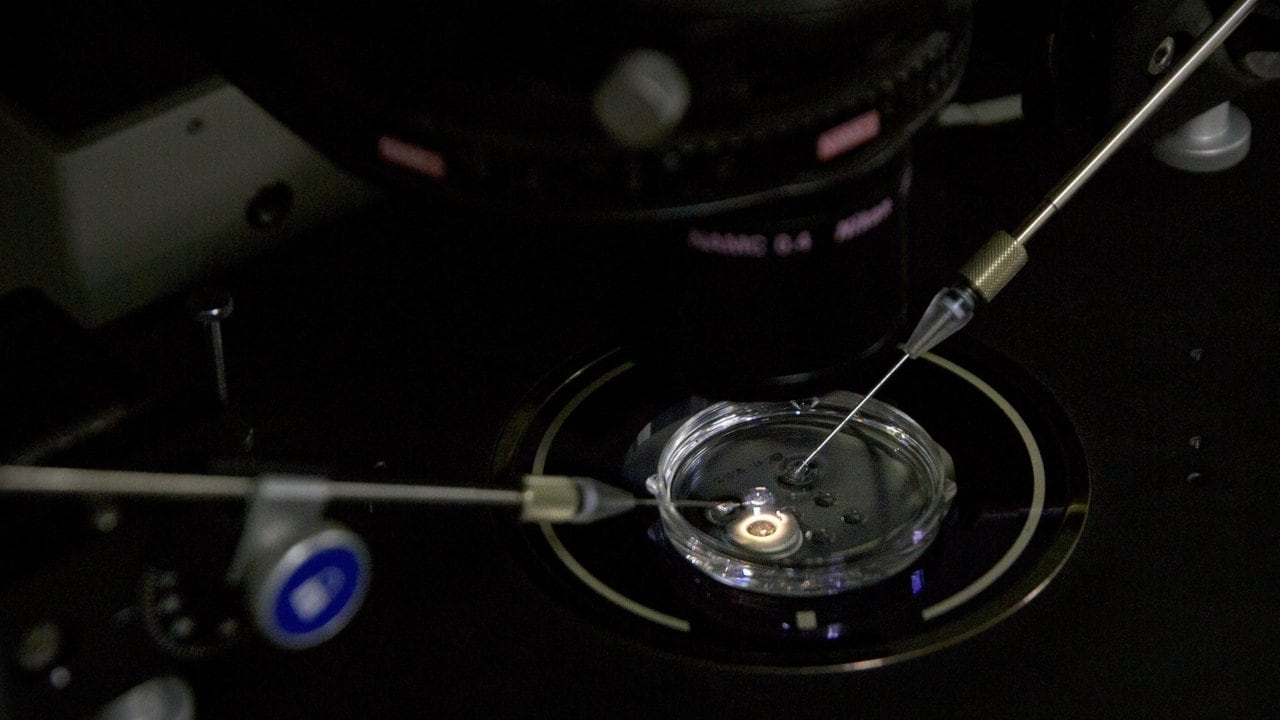

. “But this is a domain where we should be asking questions first. And maybe never shooting. What’s the rush?” [caption id=“attachment_5624541” align=“alignnone” width=“1280”] An image of the IVF procedure used in the gene-editing experiment. AP[/caption] “We don’t need to be mucking around with the genes of future children,” Marcy Darnovsky, human biotechnology expert,

told NPR

. “This could open the door to a world where people who were born genetically modified are thought to be superior to others, and we would have a society of people who are considered to be genetic haves and genetic have-nots.” And perhaps that’s exactly right. But, since CRISPR can’t be uninvented now, it may serve us well to look into the benefits that the technology can offer people without causing any harm – responsibly. Based on the report, it looks like that’s exactly what Egli is trying to do.

An image of the IVF procedure used in the gene-editing experiment. AP[/caption] “We don’t need to be mucking around with the genes of future children,” Marcy Darnovsky, human biotechnology expert,

told NPR

. “This could open the door to a world where people who were born genetically modified are thought to be superior to others, and we would have a society of people who are considered to be genetic haves and genetic have-nots.” And perhaps that’s exactly right. But, since CRISPR can’t be uninvented now, it may serve us well to look into the benefits that the technology can offer people without causing any harm – responsibly. Based on the report, it looks like that’s exactly what Egli is trying to do.

)