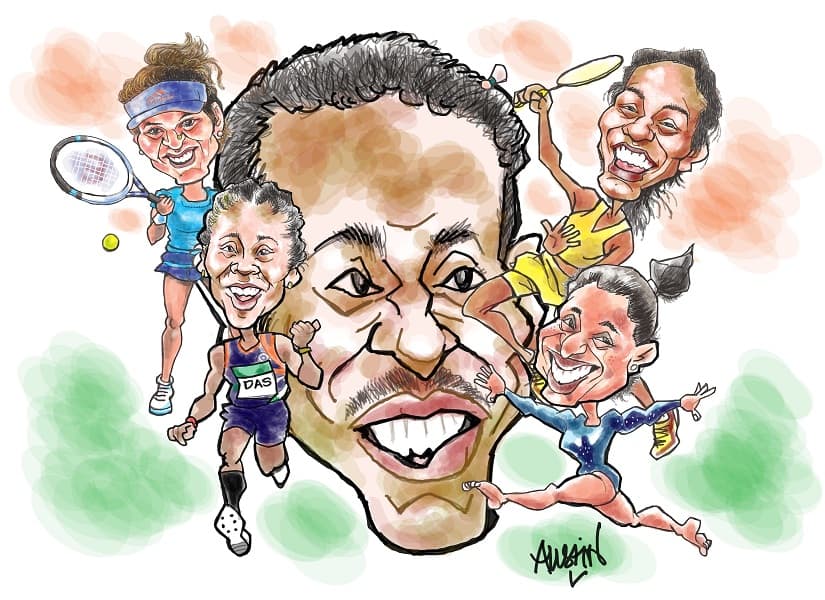

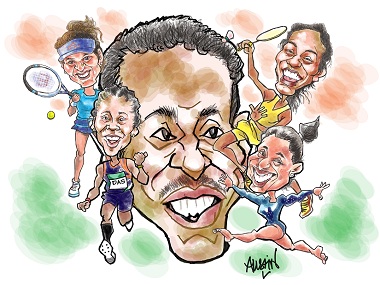

Swapna Barman of Jalpaiguri in West Bengal recently won the grueling heptathlon gold at the 2018 Asian Games. Earlier at the same games, Rahi Sarnobat from Kolhapur in Maharashtra won the 25-metre pistol event. In the men’s track and field events, middle-distance runner, Jinson Johnson of Kozhikode, in Kerala, won a silver and a gold in the 800-metre and 1,500-metre events respectively, while Arpinder Singh of Amritsar, Punjab won the triple-jump title. These four athletes came from diverse cultures, from four different corners of the country and spoke different languages. On the victory podium at Palembang, along with their other medal-winning compatriots, there was one thing that bound them — they were Indians first. They looked on with pride as the Indian tricolour was hoisted and the ‘Jana Gana Mana’ rendered. What’s more, they gave a billion Indians a reason to be proud too. At a time when communal and sectarian tensions, terror plots, political rhetoric etc are the order of the day, there is one factor that still binds us — sport. Therefore, when the union sports minister, Colonel Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore announced recently that school syllabi — academic year 2019-20 onwards — would be reduced and more time would be devoted to sports in the curriculum, it was welcomed by most forward-looking Indians. As success guru Jay Shetty puts it, Indian parents gave their kids only three career options till the turn of the millennium — doctor, lawyer or failure. Thankfully, attitudes have changed in recent times and youngsters who have an inclination towards sports are being encouraged and supported by their families. 24-hour sports channels, increased corporate interest in sport and games, and icons like Sachin Tendulkar, Virat Kohli, Sunil Chhetri, Sania Mirza, Saina Nehwal, PV Sindhu et al may have contributed to this huge mindset change. [caption id=“attachment_5089871” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Colonel Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore announced recently that academic year 2019-20 onwards, more time would be devoted to sports in school curricula. Illustration courtesy Austin Coutinho[/caption] In most developed countries, sport is a way of life. Americans, for instance, believe that sport reaches across dividing lines of age, income, geography, gender and ethnicity. For them sport is a shared language and therefore the study of sport provides unique insights into American life. In most European countries, and a few advanced Asian countries, well-developed youth programmes ensure grooming of outstanding sports talent; recreational sports are also a part of everyday life there. As envisioned by Colonel Rathore, making sport an integral part of Indian school and college curricula won’t be an easy task. We will be naïve to believe that it will be easily assimilated into the age-old education system, where the philosophy still is: Khelogey kudogey to banogey kharab; padogey likhogey to banogey nawab. (If you play, you’ll be spoilt; if you study, you’ll become a king.) Having worked with a few institutions on an honorary basis and having helped them to set up sports academies of their own, I have seen the insecurity that exists among teachers who have been trained as ‘physical trainers’, when professional sportsmen and coaches enter their field. Moreover, the senior teachers of these institutions believe that sport is an unnecessary evil and that it affects academic performances. Besides convincing school authorities at the national level to reduce their syllabuses — which is a complex task in itself — the sports minister will have his work cut out to set up committees in every state and district to see that the new sports policy is implemented religiously. A silver medalist at the Olympics, Colonel Rathore would know how the system works. If, therefore, he is going to rely solely on district sports officers to execute his scheme, he should brace himself up for some huge disappointments. Many of the schools and colleges in rural areas, and even in a world-class city like Mumbai, do not possess the basic infrastructure to promote sports. Decent grounds and sporting facilities are hard to come by and quality sports material is expensive. Finding good coaches, in large numbers, to work with school and college children is another challenge the sports minister will have to deal with. Therefore, before implementing the scheme, he will probably do well to study its various requirements. The ultimate aim of the sports minister’s scheme will be to create a sports culture in the country. Students taking up sport at the school and college level will be hooked onto one game or another, whether they take it up professionally or not. If sport is successfully made a part of education in India — and I sincerely hope it is — the next task for the sports and youth services departments of every Indian state will be to provide community sporting facilities, at reasonable costs, in all districts and towns It is the schools, colleges and the community sports centres that will create Asian and Olympic champions. The sports minister seems to have the right intentions and therefore it is hoped that the scheme will be supported wholeheartedly by educationists as well as legislators. Sport is now a multi-billion dollar industry the world over. It has a positive impact on society and has the capacity to create jobs and entrepreneurships besides earning foreign exchange for the country in the form of tourism money. Sports management institutions have now started blooming all over the country in anticipation of the sporting boom in India. There are already thousands of jobs waiting to be taken up and these will only grow in the coming years. Sports, without any doubt, help create national pride. The story of Barman, a rickshaw puller’s daughter, winning the heptathlon gold despite a toothache — and the 12 toes that she had to push into her shoes — has struck a chord with Indian sports fans. Also, the story of Arpinder’s father mortgaging his property to finance his training has touched quite a few Indians following the Asian Games. It is this feeling of patriotism that will help create champions of the future. Ask youngsters who their role models are, and I am sure most of them will name an athlete. At a time when video games are the real pastime and overeating is the norm, sportspersons can play an important role in getting youngsters to take up a sport and get rid of their flab. After India won the Test match at Trent Bridge in August, skipper Kohli said, at the presentation, that the team would like to dedicate the victory to the victims of the Kerala floods. Kohli’s statement would have drawn the cricket playing world’s attention to the natural disaster in ‘God’s Own Country’ and encouraged so many cricket fans to donate, in cash and kind, to the cause. India, at the time of writing this piece, lies eighth in the medals tally at the Asian Games of 2018. At the inaugural games held in Delhi, in 1951, India had finished second to Japan with 15 gold medals and 51 medals in all. In 1982, when the games were again held in Delhi, India, winning 13 gold medals had finished fifth behind China, Japan, South Korea and North Korea. This only means that China, Japan, the Koreas and Iran — besides the cash-rich Bahrain and Qatar — have marched ahead of India in creating a sporting culture for their people. Therefore, it is imperative that Colonel Rathore’s programme, at the school and college level, be implemented without any delay. More importantly, the programme needs to be put into operation in a way that it does not fail. Only then can we dream of leading the medals tally, at the Asian Games, 20 years from now. The author is a caricaturist and sportswriter. A former fast bowler and coach, he is now a sought-after mental toughness trainer.

The ultimate aim of Rathore’s scheme is to create a sports culture in India

Austin Coutinho is a sportswriter and cartoonist based in Mumbai. Formerly a fast bowler who was a Ranji Trophy probable in the 1980s for the city, Coutinho retired as senior manager (CRM) from Rashtriya Chemicals & Fertilizers in December 2014. Coutinho was former president of the Mumbai District Football Association, a coaching committee member of the Mumbai Cricket Association, and a member of Maharashtra’s Sport Committee. A coach and mental trainer, he has mentored some top class cricketers and footballers. Coutinho has also authored 6 books on sport and has contributed articles, cartoons and quizzes to some of the best newspapers and sports portals in the country. see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)