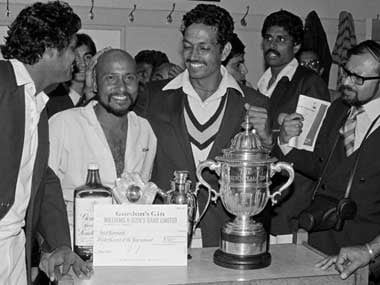

Imagine if the ICC had decided the 1983 World Cup needed to be “competitive”. At that stage, India had a World Cup record of 1-5. Their sole victory had come against East Indies in 1975. Four years later, India lost all their games, including to Sri Lanka, one of the original minnows. Imagine that the ICC decided the tournament would only feature six teams – down from eight – and India would not have automatic entry because of its lousy record. So Balwinder Singh Sandhu never bowls Gordon Greenidge, Kapil Dev never catches Viv Richards, and the fairytale of India beating the West Indies never becomes a reality. The Reliance World Cup in 1987 never takes place and cricket mania never sweeps across India. [caption id=“attachment_2108677” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Celebrations in the Indian dressing-room after India’s victory over the West Indies in the World Cup Final at Lord’s cricket ground in London, 25th June 1983: Getty images[/caption] Since we know what happened in 1983, the notion sounds absurd. But the idea of India winning the World Cup in 1983 was a crazy one before the tournament started. India were 66 to 1 outsiders and were not even expected to make the semi-finals. Sri Lanka only became a Test-playing country in 1982. Fourteen years later, the little island that could beat big, bad Australia in the World Cup final in Lahore. It was a victory nobody had predicted and no one could have. Therein lies the tragedy of the ICC’s decision to shrink the World Cup from 14 to 10 teams for the 2019 and 2023 World Cups. Restricting the participation of lesser countries (lesser only because the ICC has relegated them to that status) risks stripping the tournament of romance and denies the World Cup the very ingredient that makes sports compelling – its unpredictability. It appears in the ICC’s version of the story, Goliath must always beat David. And by assuming the future will be like the present, the ICC is betting nothing will change, which goes against the grain of history (and is also crazy). Lopsided games aren’t restricted to Associate teams either. All four games on opening weekend of the 2015 World Cup were blowouts. The winning margins were 98 runs, 111 runs, 62 runs and 77 runs respectively. The losing teams were Sri Lanka, England, Zimbabwe and Pakistan – all proud Test card carrying countries. It took an Associate team to produce the best game of the tournament so far. Ireland’s four-wicket win over the West Indies made them the only team to chase over 300 in the World Cup three times. They have now beaten Pakistan, England and the West Indies across three World Cup tournaments. Yet the other Full Members won’t let them into the club (or even agree to play bilateral ODI series against Ireland regularly). Even Scotland, which has never won a World Cup game, put on a better show, losing by only three wickets to New Zealand despite being bowled out for 142 batting first. And the United Arab Emirates, an actual amateur team, came close to beating Zimbabwe in their opening game. The 2015 World Cup would also be immeasurably poorer without Afghanistan’s uplifting story of hope and desire overcoming war and calamity.

According to

ESPNcricinfo, Afghan wicketkeeper Afsar Zazai’s “family live in a small house with a temporary roof that can’t offer proper protection from the snow." And two years ago, Afghanistan captain Mohammad Nabi’s father was kidnapped from his car and went missing for two months. To deny them this opportunity, to take away the possibility of glory on the sport’s biggest stage, is tantamount to cruel and unusual punishment. William Porterfield, the Ireland captain, captured the absurdity of cricket’s hierarchy perfectly after the match. “I actually hate the term upsets, anything from members to associates,” he said. “I don’t see why a team has to be an associate and a team has to be a full member. It’s like sure you’re ranked or whatever. It’s not like that in any other sport, so I don’t see why it has to be like that in ours.” As both a spectacle and a mirror of humanity, sport at its best offers excellence or hope. Or both. The 2008 Wimbledon final between Federer and Nadal was thrilling because it was transcendent. But the Rumble in the Jungle is a boxing touchstone because Muhammad Ali, knocked out the champion, George Foreman, and not the other way around. We treasure greatness but everyone loves an underdog. In an era when other major sports are expanding– the FIFA World Cup has grown to 32 teams and there are calls to expand it to 40 – cricket’s rulers have decided they would rather ring fence their sport in order to to preserve what they have. For them sports is a business first and like all businesses, they seek to protect their market. The irony is that the likes of India and Sri Lanka now deny others the very opportunities that allowed them to prosper. But the world will turn with or without them. Those who resist change are typically the ones who end up overwhelmed by it. The warning signs are already there. Kenya made the semi-finals of the 2003 World Cup but a combination of mismanagement and

lack of support

from the Test playing countries – Kenya played 18 ODIs against Full Members in the year and a half before that World Cup but just 11 over the next three years - led to them falling off the map. It would be a terrible shame if cricket lost Ireland and Afghanistan and the Netherlands and all the others too.

Celebrations in the Indian dressing-room after India’s victory over the West Indies in the World Cup Final at Lord’s cricket ground in London, 25th June 1983: Getty images[/caption] Since we know what happened in 1983, the notion sounds absurd. But the idea of India winning the World Cup in 1983 was a crazy one before the tournament started. India were 66 to 1 outsiders and were not even expected to make the semi-finals. Sri Lanka only became a Test-playing country in 1982. Fourteen years later, the little island that could beat big, bad Australia in the World Cup final in Lahore. It was a victory nobody had predicted and no one could have. Therein lies the tragedy of the ICC’s decision to shrink the World Cup from 14 to 10 teams for the 2019 and 2023 World Cups. Restricting the participation of lesser countries (lesser only because the ICC has relegated them to that status) risks stripping the tournament of romance and denies the World Cup the very ingredient that makes sports compelling – its unpredictability. It appears in the ICC’s version of the story, Goliath must always beat David. And by assuming the future will be like the present, the ICC is betting nothing will change, which goes against the grain of history (and is also crazy). Lopsided games aren’t restricted to Associate teams either. All four games on opening weekend of the 2015 World Cup were blowouts. The winning margins were 98 runs, 111 runs, 62 runs and 77 runs respectively. The losing teams were Sri Lanka, England, Zimbabwe and Pakistan – all proud Test card carrying countries. It took an Associate team to produce the best game of the tournament so far. Ireland’s four-wicket win over the West Indies made them the only team to chase over 300 in the World Cup three times. They have now beaten Pakistan, England and the West Indies across three World Cup tournaments. Yet the other Full Members won’t let them into the club (or even agree to play bilateral ODI series against Ireland regularly). Even Scotland, which has never won a World Cup game, put on a better show, losing by only three wickets to New Zealand despite being bowled out for 142 batting first. And the United Arab Emirates, an actual amateur team, came close to beating Zimbabwe in their opening game. The 2015 World Cup would also be immeasurably poorer without Afghanistan’s uplifting story of hope and desire overcoming war and calamity.

According to

ESPNcricinfo, Afghan wicketkeeper Afsar Zazai’s “family live in a small house with a temporary roof that can’t offer proper protection from the snow." And two years ago, Afghanistan captain Mohammad Nabi’s father was kidnapped from his car and went missing for two months. To deny them this opportunity, to take away the possibility of glory on the sport’s biggest stage, is tantamount to cruel and unusual punishment. William Porterfield, the Ireland captain, captured the absurdity of cricket’s hierarchy perfectly after the match. “I actually hate the term upsets, anything from members to associates,” he said. “I don’t see why a team has to be an associate and a team has to be a full member. It’s like sure you’re ranked or whatever. It’s not like that in any other sport, so I don’t see why it has to be like that in ours.” As both a spectacle and a mirror of humanity, sport at its best offers excellence or hope. Or both. The 2008 Wimbledon final between Federer and Nadal was thrilling because it was transcendent. But the Rumble in the Jungle is a boxing touchstone because Muhammad Ali, knocked out the champion, George Foreman, and not the other way around. We treasure greatness but everyone loves an underdog. In an era when other major sports are expanding– the FIFA World Cup has grown to 32 teams and there are calls to expand it to 40 – cricket’s rulers have decided they would rather ring fence their sport in order to to preserve what they have. For them sports is a business first and like all businesses, they seek to protect their market. The irony is that the likes of India and Sri Lanka now deny others the very opportunities that allowed them to prosper. But the world will turn with or without them. Those who resist change are typically the ones who end up overwhelmed by it. The warning signs are already there. Kenya made the semi-finals of the 2003 World Cup but a combination of mismanagement and

lack of support

from the Test playing countries – Kenya played 18 ODIs against Full Members in the year and a half before that World Cup but just 11 over the next three years - led to them falling off the map. It would be a terrible shame if cricket lost Ireland and Afghanistan and the Netherlands and all the others too.

Tariq Engineer is a sports tragic who willingly forgoes sleep for the pleasure of watching live events around the globe on television. His dream is to attend all four tennis Grand Slams and all four golf Grand Slams in the same year, though he is prepared to settle for Wimbledon and the Masters.

)