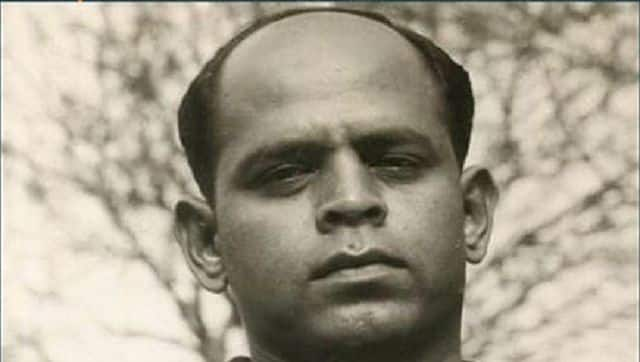

Editor’s Note: Khashaba Jadhav, independent India’s first individual Olympic medallist, will forever remain one of India’s greatest athletes. This piece is being republished to honour his Olympic journey. In a nation obsessed with statues, you’ll be hard-pressed to find one honouring Khashaba Jadhav. There’s no Bollywood biopic either so far recreating the life and times of a humble son of soil who was just 5'5" tall, but could slay giants in the wrestling arena. The legend of Khashaba Jadhav, who was India’s first individual Olympic medallist after independence, has endured the test of time solely through monochromatic images and technicolour tales passed from one generation to the other in taleems, as akharas in Maharashtra are known. The wrestlers who slog away in the taleems of Maharashtra have never met Khashaba in person, let alone watch him wrestle. He died in a road accident in 1984, but his memory lives on in the form of framed photographs that are as ubiquitous in many of these taleems as portraits of Lord Hanuman ― the patron God of wrestling in India. “In the religion of wrestling, Khashaba was right after God. That’s why if you go to any wrestling taleem across Maharashtra, you are as likely to find a photo of Khashaba as you are to see Bajrangbali’s portrait,” said Kaka Pawar, who was a Greco-Roman wrestler back in his day and now runs his own taleem in Pune. “My father passed away when I was just 13 years old. But what I remember about him is his simplicity. Look at any sportsperson, movie star, or even a politician in this day and age, you’ll see how much glamour surrounds them. My father didn’t have an iota of that despite his stature,” Ranjit Jadhav, Khashaba’s son told Firstpost. Most of what Ranjit remembers of his father is from tales he’s heard from his mother or from others. In an interview with a radio channel a few years back, Ranjit recollected how his father would never talk about him being an Olympic medallist. It was only when the senior Jadhav made him read out correspondence that a young Ranjit would get an inkling of just who his father was. [caption id=“attachment_8675081” align=“alignnone” width=“640”] An undated image of Khashaba Jadhav, who won independent India’s first individual medal at the Olympics[/caption] Two anecdotes illustrate the humility of Khashaba. In the late 1940s, he had travelled to Nashik to compete at a dangal in Maharashtra where the organisers put up one rupee as a prize for a bout featuring him. “The typical wrestlers who entered dangals at that time would be bulky or hefty. But my father was a lean man. So the organisers put up one rupee as the prize money for winning. Any wrestler would have taken offence at that. But my father fought without making a fuss and in the blink of an eye, beat his opponent by applying a dhaak move,” said Ranjit. The swift takedown by Khashaba caught the eye of a maharaja, who was in attendance. He raised the stakes by raising the prize money to Rs 51 and asked the grappler if he would fight again. Not one to turn down a fight, Khashaba agreed. Again, he won without breaking a sweat. The maharaja was so impressed that he raised the stakes again, this time offering Rs 151 for victory. Once again, there was no contest. Ranjit’s second tale is from when India were preparing to host the New Delhi Asian Games in 1982. A few days before the Games were to begin in the capital, he says, Rs 3,000 and air tickets for his father arrived requesting him to come for the torch relay. Any other athlete would have seethed at being invited at the last minute, clearly as an after-thought. But Khashaba calmly accepted the invite. The indifference of officials stalked him throughout his life. After his demise, this apathy hung over his legacy. But there are very few men who could take all of life’s slights in their stride with as much nonchalance as Khashaba. Legend has it that before the Helsinki Games, he beat Bengal’s Narayan Das twice. Yet, he was overlooked for the Indian squad the Games. It was only after he pleaded his case with the Maharaja of Patiala, a patron of the sport of wrestling, that he got a trial against Das again for a ticket to the Olympics. For the third time, Khashaba reigned and was sent to Helsinki. Pawar brings up the famous story of how Khashaba even made it to the 1952 Olympics in the first place. “Since travelling to Finland was an expensive prospect, Khashaba asked people he knew for help to raise the Rs 8,000 he needed to travel to Finland. While people in his village of Goleshwar raised Rs 1,000, his college principal, R Karadikar, raised Rs 7000 by mortgaging his own house,” said Pawar. Some accounts say that Khashaba needed the help of his college principal and villagers only because he was let down by politicians. He had approached the then Chief Minister of Bombay, Morarji Desai, for financial help. He was rudely snubbed and told to come back after the Olympics. At the 1952 Games, with the experience gained from finishing sixth at the London Olympics four years ago, he started to dominate his opponents. But then he ran into Ishii Shohachi of Japan and after a tiring duel, he finally lost. While rules at the time said there needed to be a gap between two bouts, he was asked to fight Russia’s Rashid Mamadekov right after losing to the Japanese grappler. He eventually ended with bronze. Utkarsh Kale, a freestyle wrestler in the uber-competitive 57kg weight class, says he heard a tale that Khashaba was originally told by his coaches that his bouts were not scheduled for that day. But when he reached the venue to see bouts in the other weight class, he found out he was supposed to be in action that day. “To be thrown into the deep end of the pool at a moment’s notice, and still emerging with a medal, that too at the Olympics, is remarkable,” said Kale. He added that what happened with Khashaba always served as a reminder that an athlete must prepare for anything at a competition. Pawar points out why the bronze was even more remarkable. “It was impressive for a man from rural Maharashtra who competed in mud akharas to go a stage like the Olympics and win a medal while competing on a mat. At least in my era, I had competed on a mat. At Khashaba’s time, Indians had probably never seen a mat, forget wrestling on one. “I heard that after coming back from London Olympics in 1948, he would train on a thick, stuffed quilt to prepare for competing on a mat.” *** [caption id=“attachment_8675111” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

KD Jadhav’s legend has endured the test of time solely through monochromatic images and technicolour tales passed from one generation to the other in taleems.[/caption] Just how momentous Khashaba’s medal was in the history of Indian sport can be gauged by the fact that it took another Indian 44 years ― or 11 Olympic Games ― to stand beside Khashaba on the same pedestal. Just like Khashaba, the suave, city-slicker Leander Paes also defied expectations to win a bronze medal at the Atlanta Olympics. It would be 12 more years before Sushil Kumar, a tempest of muscle and wrestling acumen, won another wrestling medal for India. Sushil’s medal at Beijing 2008 opened the floodgates for Indian wrestlers at high-profile tournaments. The following two Olympic Games yielded three medals, while there have been 14 medals at the World Championships. This success on the mat has propelled the profile of the sport. Money and fame have followed. But back in the day, when Khashaba returned from the Helsinki Games with an unlikely medal, his welcoming party comprised of just over 100 bullock carts. No garlands of currency notes. Recognition in the form of state awards did arrive, albeit too late: He was bestowed with the Shiv Chhatrapati Award, the state of Maharashtra’s top award for athletes, nearly 10 years after his death. The Arjuna Award came 16 years after he had passed away. No Padma award till date. “That man gave India its first individual Olympic medal. In return, what did India give him? He should have been the first Arjuna awardee of this country. When the state started handing out Shiv Chhatrapati Awards to athletes, he should have been the first name on the list,” said Pawar, who is an Arjuna awardee himself. Pawar says that Khashaba would have remained a name popular only in _taleem_s around the state had it not been for the National Games that Pune hosted in 1994. “That’s when people at large started to realise that it was actually possible for a man from a small village to go to the Olympics and win a medal,” said Pawar. “In Maharashtra’s dangals, wrestlers who are hefty gain instant fame. Khashaba was a small man. But his stature was bigger than any giant this state has ever produced.”

KD Jadhav’s legend has endured the test of time solely through monochromatic images and technicolour tales passed from one generation to the other in taleems.[/caption] Just how momentous Khashaba’s medal was in the history of Indian sport can be gauged by the fact that it took another Indian 44 years ― or 11 Olympic Games ― to stand beside Khashaba on the same pedestal. Just like Khashaba, the suave, city-slicker Leander Paes also defied expectations to win a bronze medal at the Atlanta Olympics. It would be 12 more years before Sushil Kumar, a tempest of muscle and wrestling acumen, won another wrestling medal for India. Sushil’s medal at Beijing 2008 opened the floodgates for Indian wrestlers at high-profile tournaments. The following two Olympic Games yielded three medals, while there have been 14 medals at the World Championships. This success on the mat has propelled the profile of the sport. Money and fame have followed. But back in the day, when Khashaba returned from the Helsinki Games with an unlikely medal, his welcoming party comprised of just over 100 bullock carts. No garlands of currency notes. Recognition in the form of state awards did arrive, albeit too late: He was bestowed with the Shiv Chhatrapati Award, the state of Maharashtra’s top award for athletes, nearly 10 years after his death. The Arjuna Award came 16 years after he had passed away. No Padma award till date. “That man gave India its first individual Olympic medal. In return, what did India give him? He should have been the first Arjuna awardee of this country. When the state started handing out Shiv Chhatrapati Awards to athletes, he should have been the first name on the list,” said Pawar, who is an Arjuna awardee himself. Pawar says that Khashaba would have remained a name popular only in _taleem_s around the state had it not been for the National Games that Pune hosted in 1994. “That’s when people at large started to realise that it was actually possible for a man from a small village to go to the Olympics and win a medal,” said Pawar. “In Maharashtra’s dangals, wrestlers who are hefty gain instant fame. Khashaba was a small man. But his stature was bigger than any giant this state has ever produced.”

Click here to read more pieces from this series

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)