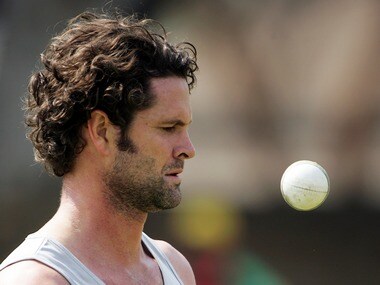

Like a satellite that cannot attain escape velocity, Cairns just can’t seem to escape rumours of match fixing. Every time he thinks he has put the whole sordid story behind him, it emerges again to pull him right back into the middle of it. The latest string of revelations based on leaked testimony from Lou Vincent and Brendon McCullum has forced Chris Cairns to come out and say he is not the mysterious Mr. X, who is believed to have been at the heart of fixing in the now defunct Indian Cricket League. [caption id=“attachment_1537057” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Chris Cairns has been forced to deny allegations of fixing once again. Reuters[/caption] In the past Cairns has successfully sued Lalit Modi for libel for saying he was a fixer, though a couple of months ago Cairns’s lawyer was arrested for perverting the cause of justice. The fact that Cairns’ name has popped up once again, and the situation continues to drag on years after the initial allegations, should make the ICC extremely uncomfortable. Typically, where there is this much smoke, there is fire and the inability of the ICC to resolve the situation one way or another makes it look ineffective at best, and unwilling at worst. It doesn’t help that cricket’s administrators don’t have a great track record when it comes to dealing with corruption in the sport. In particular, the successes of the ICC’s Anti-Corruption and Security Unit are thin on the ground, as the Telegraph reports: “A document seen by Telegraph Sport revealed the ACSU chased 281 lines of inquiry in 2011, including the bookie [Lous] Vincent has claimed paid him in the UK, but failed to land a conviction. Nobody has an answer as to why. “The report was never intended to be made public because it was felt the ACSU would be embarrassed by its poor conversion rate.” There are multiple damning indictments of the ICC in those two paragraphs. A zero percent conviction rate means cricket would not be worse off if the ACSU simply did not exist at all. The lack of explanation suggests nobody is able to explain why it has failed so appallingly. And the refusal to make the report public proves the ICC is more concerned about looking bad than actually preventing corruption. You can bet that if the ACSU had successfully prosecuted a majority of those inquiries, the numbers would have headlined sports pages around the world. On the other hand, releasing the report might have forced a global conversation on how to make the ACSU more effective. The recent decision to review the ACSU makes it clear even the ICC believes this is a conversation that needs to be had. The problem is shrouding the whole process in secrecy defeats the entier purpose. You can’t purport to clean the game of shady practices by indulging in your own set of shady practices. To be fair, whistle blowers need protection. Players need to be able to come forward and give evidence with the knowledge their testimony will remain confidential. They should also be given assurances their careers will not suffer. But the protection of their identity should last only until the investigation is complete. In the wider world, evidence given in a court room is public. The Oscar Pistorius murder trial, for example, is being live tweeted and broadcast around the world. So it should be with cricket. The damage to reputation is overblown in any case. Both Herschelle Gibbs and Nicky Boje continued to play for South Africa after being linked to fixing in 2000 by the CBI. Wasim Akram can hardly be said to have suffered for being named in the Justice Qayyum report. What matters is finding the truth. Cricket doesn’t have to look far to discover the risks of its current course. The constant rumours and innuendo about Lance Armstrong and performance enhancing drugs first poisoned the image of professional cycling before the rising weight of evidence eventually toppled Armstrong. It is a morality tale the sport would do well to heed.

A zero percent conviction rate means cricket would not be worse off if the ACSU simply did not exist at all. The lack of explanation suggests nobody is able to explain why it has failed so appallingly.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by Tariq Engineer

Tariq Engineer is a sports tragic who willingly forgoes sleep for the pleasure of watching live events around the globe on television. His dream is to attend all four tennis Grand Slams and all four golf Grand Slams in the same year, though he is prepared to settle for Wimbledon and the Masters. see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)