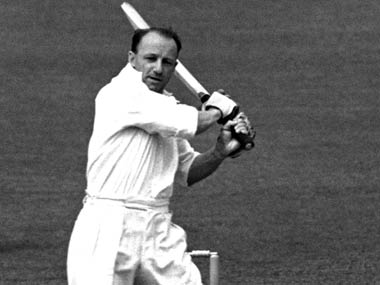

The Bodyline series was the stuff of myth and legend. It gave rise to drama and battles that are still waged in the watering holes of this world. It was the series that saw Don Bradman being tamed by an obdurate opponent; it was a series that saw a theory being executed perfectly on the field of play; it was a series between two evenly matched sides and in the end, it was England that came out on top. February 28th 2013 was the 80th anniversary of the conclusion to one of the finest – and certainly the most controversial – test series ever played. In The Spectator, Alex Massie walked down memory lane and had a look at the Bodyline series. It is also sometimes forgotten how good Woodfull’s Australian side was. A lack of fast-bowling was its only weakness. Nevertheless Australia’s doughty skipper could, at various times, call on the talents of McCabe, Ponsford, Richardson, Kippax, O’Reilly and Grimmet. And then there was Bradman. Ordinarily his presence ensured that, effectively, Australia pitted 12 players against the opposition’s 11. Jardine’s challenge – and his achievement – was to even the odds. Reduce Bradman to mere mortal status and the game would revert to the traditional 11 vs 11. And he did it. By god he did it. Many people attempted to solve the Bradman Problem; Jardine was the only man to do so. Even then it was, like Waterloo, a damn close run thing. Of the many brain-boggling statistics demonstrating Bradman’s pre-eminence one of the most startling is that while he made 29 test centuries he was only 13 times dismissed between 50 and 100. That is, having reached 50 Bradman was, over the course of his career, more than twice as likely to make a century. No-one has ever matched this. [caption id=“attachment_644727” align=“alignright” width=“380”]  England dulled Bradman and won the series. Getty Images[/caption] Recall the scale of the challenge Jardine faced. In 1930 Bradman had flayed England for 974 runs at an average of 139. He made seven test innings that summer and reached at least a century in four of them. The following Australian summer he skelped the South Africans for 806 runs at an average of 201. His five innings that summer produced four centuries. As Percy Fender, Jardine’s captain at Surrey, had said in 1930 “something new will have to be introduced to curb Bradman”. And Jardine had to find that something new for a series to be played on dull Australian pitches and in conditions unlikely to prove conducive to swing bowling. The prevailing conditions – including a still-batsman-friendly LBW law – dictated English tactics almost as much as did the need to counter Bradman. The ball would be softening after no more than 15 overs; allowing the Australian batsmen the freedom of the off-side would have been an invitation to make hay. Bodyline was a means of rebalancing the game, chipping away at the in-built advantage batsmen enjoyed at the time and (especially) in those Australian conditions. Read the full piece on The Spectator HERE

February 28th 2013 was the 80th anniversary of the conclusion to one of the finest – and certainly the most controversial – test series ever played.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)