Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi has emerged from his three-day fast for sadbhavana with his political profile embellished by a string of

public endorsements by BJP leaders

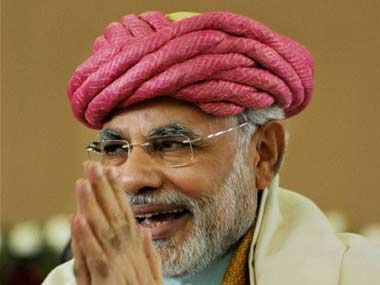

and media commentaries virtually anointing him the Prime Minister-in-waiting. Although parliamentary elections are more than two years away, the notion that with his Sadbhavana Mission, Modi has effectively staked a strong bid for the top job is gaining wider currency in media commentaries. And although Modi still has some unfinished business to accomplish in Gujarat – that is, win big in the 2012 Gujarat Assembly elections – before he can realistically set his sights on faraway Delhi, it’s fair to say that he has won a critical mass of adherents within his party who will be happy to see him unfurl the tricolour from the ramparts of the Red Fort in some years. [caption id=“attachment_87029” align=“alignright” width=“380” caption=“Narendra Modi will likely face three challenges in transitioning from a State-level satrap to national-level leader. AFP Photo”]

[/caption] To the extent that Modi’s three-day fast was, despite his own protestations, the platform for ceaseless chatter about his elevation to national leadership – even his detractors were forced to address it – Modi has the advantage of having set the media narrative. The fact that he has a couple of years to plan out his campaign gives him an early-mover advantage. So, what next for Modi? If indeed Delhi is in his sights, how does the political course run from here on? What are his strengths, and just as important, what hurdles will he face on that journey? Modi will likely face three challenges in transitioning himself from a powerful State-level satrap to a national-level leader. Managing right-wing expectations. For a leader who was until a few years ago perceived as the Field-Marshal of the Hindutva army, Modi has sought to project an image of himself as more inclusive. That’s probably because he calculates that beyond Gujarat, the space for strident Hindutva politics is limited, given the social dynamics of India today. Even within Gujarat, he has in recent elections discernably moved away from the politics of right-wing nationalism and religious conservatism, and embraced the mantra of development as his platform. This has in the past caused some strains in his relationship with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad,

which linger to this day

. As Modi moves ever closer to the Centre – geographically and in a political sense – Modi would be leaving his right flank open, which leaders like Pravin Togadia will be looking to exploit. Within Gujarat, thus far, Modi has been able to neutralise such opposition, but how he manages these political nuances will be on test as he primes himself for national leadership. Law and order challenges. In response to anyone who cites the 2002 Gujarat riots as a stain on his record in office, Modi cites the fact that there have been no riots since then as proof that his administration is effective in maintaining law and order. In fact, as

even Congress leaders in Gujarat acknowledge

, “the fact that Modi clearly has aspirations for national leadership makes him, ironically, one of the greatest protectors of communal harmony.” That’s because Modi knows that another outbreak like 2002 would doom his chances, and he will therefore be particularly zealous to ensure there are no further problems on his watch. Yet, that very reason provides the incentive for Modi’s detractors to whip up trouble, including communal trouble, in Gujarat as a way of impeding his political progress. Given the combustible nature of communal relations in the State, with a long history of riots, the challenge of maintaining the harmony that Modi wants now to ensure will be particularly daunting. Even in the absence of communal trouble, his detractors are bound to repeatedly invoke the 2002 Gujarat riots as a way of holding him back. His responses to these challenges could be critical to his progress. Style of governance. In public appearances, and particularly at the three-day fast, where he played along with various exotic headgear adornments thrust upon him, Modi presents an easygoing image. But in private, according to

accounts from those in his inner administrative circles

, he is considered an “insular, distrustful person” who rules “more by fear and intimidation than by inclusiveness and consensus, and is rude, condescending and often derogatory to even high-level party officials.” In some cases, even his ministers don’t come to know of decisions that affect their portfolios. It’s true that such a leadership style may sit well with those who want a kick-ass CEO who gets the job done, but such a style may not endear him to BJP’s alliance partners at a national level. None of these is an insurmountable challenge for Modi, who has thus far shown himself to be astute at playing his political cards. Yet, it’s worth flagging them as the hurdles that stand between him and the political destiny he seeks.

[/caption] To the extent that Modi’s three-day fast was, despite his own protestations, the platform for ceaseless chatter about his elevation to national leadership – even his detractors were forced to address it – Modi has the advantage of having set the media narrative. The fact that he has a couple of years to plan out his campaign gives him an early-mover advantage. So, what next for Modi? If indeed Delhi is in his sights, how does the political course run from here on? What are his strengths, and just as important, what hurdles will he face on that journey? Modi will likely face three challenges in transitioning himself from a powerful State-level satrap to a national-level leader. Managing right-wing expectations. For a leader who was until a few years ago perceived as the Field-Marshal of the Hindutva army, Modi has sought to project an image of himself as more inclusive. That’s probably because he calculates that beyond Gujarat, the space for strident Hindutva politics is limited, given the social dynamics of India today. Even within Gujarat, he has in recent elections discernably moved away from the politics of right-wing nationalism and religious conservatism, and embraced the mantra of development as his platform. This has in the past caused some strains in his relationship with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad,

which linger to this day

. As Modi moves ever closer to the Centre – geographically and in a political sense – Modi would be leaving his right flank open, which leaders like Pravin Togadia will be looking to exploit. Within Gujarat, thus far, Modi has been able to neutralise such opposition, but how he manages these political nuances will be on test as he primes himself for national leadership. Law and order challenges. In response to anyone who cites the 2002 Gujarat riots as a stain on his record in office, Modi cites the fact that there have been no riots since then as proof that his administration is effective in maintaining law and order. In fact, as

even Congress leaders in Gujarat acknowledge

, “the fact that Modi clearly has aspirations for national leadership makes him, ironically, one of the greatest protectors of communal harmony.” That’s because Modi knows that another outbreak like 2002 would doom his chances, and he will therefore be particularly zealous to ensure there are no further problems on his watch. Yet, that very reason provides the incentive for Modi’s detractors to whip up trouble, including communal trouble, in Gujarat as a way of impeding his political progress. Given the combustible nature of communal relations in the State, with a long history of riots, the challenge of maintaining the harmony that Modi wants now to ensure will be particularly daunting. Even in the absence of communal trouble, his detractors are bound to repeatedly invoke the 2002 Gujarat riots as a way of holding him back. His responses to these challenges could be critical to his progress. Style of governance. In public appearances, and particularly at the three-day fast, where he played along with various exotic headgear adornments thrust upon him, Modi presents an easygoing image. But in private, according to

accounts from those in his inner administrative circles

, he is considered an “insular, distrustful person” who rules “more by fear and intimidation than by inclusiveness and consensus, and is rude, condescending and often derogatory to even high-level party officials.” In some cases, even his ministers don’t come to know of decisions that affect their portfolios. It’s true that such a leadership style may sit well with those who want a kick-ass CEO who gets the job done, but such a style may not endear him to BJP’s alliance partners at a national level. None of these is an insurmountable challenge for Modi, who has thus far shown himself to be astute at playing his political cards. Yet, it’s worth flagging them as the hurdles that stand between him and the political destiny he seeks.

Venky Vembu attained his first Fifteen Minutes of Fame in 1984, on the threshold of his career, when paparazzi pictures of him with Maneka Gandhi were splashed in the world media under the mischievous tag ‘International Affairs’. But that’s a story he’s saving up for his memoirs… Over 25 years, Venky worked in The Indian Express, Frontline newsmagazine, Outlook Money and DNA, before joining FirstPost ahead of its launch. Additionally, he has been published, at various times, in, among other publications, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, Outlook, and Outlook Traveller.

)