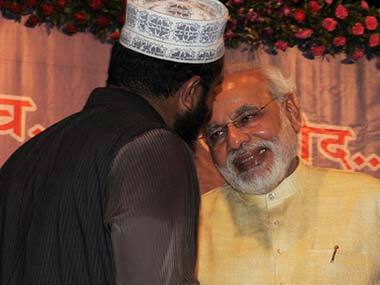

Finally, yes, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has accepted the presence of fear among the Muslims of India. But what remains ambiguous is the nature of this fear: Whom do they fear? What are they afraid of? Is the Prime Minister’s prognosis of the community’s apprehensions rooted in reality? All these questions arise from the statement released by the president of Delhi’s India Islamic Cultural Centre, Sirajuddin Qureshi, following his 35-minute meeting with Modi on 26 June. Just about every newspaper had its reporter speak directly to Qureshi, who further elaborated upon the statement he had released. [caption id=“attachment_1595105” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

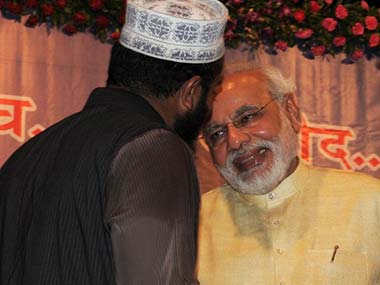

AFP[/caption] Piecing together these multiple accounts, we get a glimpse into Modi’s mindset. He exhorted the Muslims to “come out of fear politics” and commended the fact that 9 percent of them ‘voted for him’. He also promised to look into the alleged false implication of Muslim youths in terror cases, and resolved to provide equal development opportunities and modern education to the community. It is possible that Qureshi’s perception of the meeting could vary significantly from Modi’s. However, since the Prime Minister’s Office didn’t issue a statement on the meeting, we can assume Qureshi has correctly articulated Modi’s insights into the problems bedevilling the Muslim community. These media accounts can be parsed to say that: One, Modi hasn’t dubbed as absurd the community’s suspicion that its boys are being falsely implicated in terror cases. But this also doesn’t imply that he accepts that the community’s suspicions have an element of truth. Two, he doesn’t believe Muslims, because of their backwardness, require preferential or compensatory treatment to improve their socio-economic conditions. Three, he feels Muslims should take to modern education, a statement that can be seen as an implicit critique of the madrassa system of imparting knowledge. Modi’s position on these three issues is not unique, reflecting as it does, in many ways, that of the BJP’s. He, however, might signal a break from the past if he were to, say, appoint a committee of eminent people to review terror cases involving Muslim youths, as Qureshi claimed to have proposed. Modi implicitly believes Muslims are strongly disinclined to vote him or his party, for he wouldn’t have otherwise appreciated the negligible 9 percent of them who did end up voting for him. It is in this context that his exhortation to Muslims to “come out of fear politics” should be analysed, even as he promised to address their apprehensions. Therefore, the question: What is this “fear politics” that the Prime Minister is alluding to? Judging from the BJP’s past rhetoric, it would seem that Modi, like his party, believes the fear of the Muslim community is unfounded and unreal. According to this narrative the non-BJP parties are accused of aggravating the insecurities of Muslims and breeding in them the paranoia of the Sangh Parivar, in the hopes of garnering their votes. Not only is the fear of Muslims dismissed as unfounded, they are perceived to be gullible who, therefore, misconstrue the existing political reality. But this narrative ignores the shadow of the past looming over the present. For one, the Sangh’s Hindutva ideology is pitted against the Muslims, often with devastating consequences. Innumerable commissions of inquiry have indicted the RSS for fomenting violence, beginning from the Hindu-Muslim rioting in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, in 1961, which has been billed as the first major communal conflagration post-Independence. In most recent times, LK Advani’s rath yatra of 1990, the demolition of the Babri Masjid two years later, and the horrific Gujarat riots of 2002 have stoked the fears Muslims have had about the BJP. No doubt, other political formations seek to harness this fear of Muslims, at times aggravating their insecurities. Nevertheless, it would be grossly unjust, even contemptuous, to dismiss the Muslim community’s apprehensions about its security as simply the creation of those who are the rivals of the BJP. Forget the past, turn the spotlight on the Modi government and ask the question: Have the first 30 days of its rule instilled robust confidence in the community about its future, or allayed its fears about the BJP? Undoubtedly, the Muslims feared the worst about a BJP government commanding a majority of its own in the Lok Sabha. True, no large-scale rioting has broken out, yet the lynching of a Muslim youth in Pune, who was in no way connected to a Facebook post that disparaged Shivaji and triggered protests, underlines the difficulty in controlling the Hindu hotheads, who have interpreted Modi’s victory as licence to flex their muscles. This was also the theme of the rioting in Mewat, Haryana, where a vehicular accident was given a communal twist to create, or widen, a chasm between the Hindus and Muslims. Incidentally, both Haryana and Maharashtra go to polls later in the year, suggesting the Sangh would put to use its old technique of harnessing communal discord for political mobilisation. And apart from a minor mention in the President’s joint address to Parliament about the Pune techie murder, we haven’t really heard Modi speak on these issues. Perhaps these are relatively too minor for the Prime Minister to intervene. Yet, arguably, this isn’t the political ambience in which the Muslims can be encouraged to “come out of fear politics.” To build such an enabling ambience Modi could or should visit Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, where the grisly communal riotings of last year have disrupted the decades-old amity between the Jats and Muslims. A wedge between the two social groups was further driven because of the BJP’s election campaign. For instance, those accused of fomenting riots were facilitated at a BJP rally which Modi himself addressed. All these could have been described, even though repugnant, as typically the strategy of the BJP to maximize its electoral gains. But the past intruded upon the present on the day one of the accused, Sanjeev Baliyan, was included in the Union Council of Ministers. And to think, the BJP had justifiably joined the chorus for the dropping of Jagdish Tytler from the Congress ministry and the denial of an election ticket to Sajjan Kumar, both alleged to have played a role in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. [caption id=“attachment_1595111” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

AFP[/caption] Piecing together these multiple accounts, we get a glimpse into Modi’s mindset. He exhorted the Muslims to “come out of fear politics” and commended the fact that 9 percent of them ‘voted for him’. He also promised to look into the alleged false implication of Muslim youths in terror cases, and resolved to provide equal development opportunities and modern education to the community. It is possible that Qureshi’s perception of the meeting could vary significantly from Modi’s. However, since the Prime Minister’s Office didn’t issue a statement on the meeting, we can assume Qureshi has correctly articulated Modi’s insights into the problems bedevilling the Muslim community. These media accounts can be parsed to say that: One, Modi hasn’t dubbed as absurd the community’s suspicion that its boys are being falsely implicated in terror cases. But this also doesn’t imply that he accepts that the community’s suspicions have an element of truth. Two, he doesn’t believe Muslims, because of their backwardness, require preferential or compensatory treatment to improve their socio-economic conditions. Three, he feels Muslims should take to modern education, a statement that can be seen as an implicit critique of the madrassa system of imparting knowledge. Modi’s position on these three issues is not unique, reflecting as it does, in many ways, that of the BJP’s. He, however, might signal a break from the past if he were to, say, appoint a committee of eminent people to review terror cases involving Muslim youths, as Qureshi claimed to have proposed. Modi implicitly believes Muslims are strongly disinclined to vote him or his party, for he wouldn’t have otherwise appreciated the negligible 9 percent of them who did end up voting for him. It is in this context that his exhortation to Muslims to “come out of fear politics” should be analysed, even as he promised to address their apprehensions. Therefore, the question: What is this “fear politics” that the Prime Minister is alluding to? Judging from the BJP’s past rhetoric, it would seem that Modi, like his party, believes the fear of the Muslim community is unfounded and unreal. According to this narrative the non-BJP parties are accused of aggravating the insecurities of Muslims and breeding in them the paranoia of the Sangh Parivar, in the hopes of garnering their votes. Not only is the fear of Muslims dismissed as unfounded, they are perceived to be gullible who, therefore, misconstrue the existing political reality. But this narrative ignores the shadow of the past looming over the present. For one, the Sangh’s Hindutva ideology is pitted against the Muslims, often with devastating consequences. Innumerable commissions of inquiry have indicted the RSS for fomenting violence, beginning from the Hindu-Muslim rioting in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, in 1961, which has been billed as the first major communal conflagration post-Independence. In most recent times, LK Advani’s rath yatra of 1990, the demolition of the Babri Masjid two years later, and the horrific Gujarat riots of 2002 have stoked the fears Muslims have had about the BJP. No doubt, other political formations seek to harness this fear of Muslims, at times aggravating their insecurities. Nevertheless, it would be grossly unjust, even contemptuous, to dismiss the Muslim community’s apprehensions about its security as simply the creation of those who are the rivals of the BJP. Forget the past, turn the spotlight on the Modi government and ask the question: Have the first 30 days of its rule instilled robust confidence in the community about its future, or allayed its fears about the BJP? Undoubtedly, the Muslims feared the worst about a BJP government commanding a majority of its own in the Lok Sabha. True, no large-scale rioting has broken out, yet the lynching of a Muslim youth in Pune, who was in no way connected to a Facebook post that disparaged Shivaji and triggered protests, underlines the difficulty in controlling the Hindu hotheads, who have interpreted Modi’s victory as licence to flex their muscles. This was also the theme of the rioting in Mewat, Haryana, where a vehicular accident was given a communal twist to create, or widen, a chasm between the Hindus and Muslims. Incidentally, both Haryana and Maharashtra go to polls later in the year, suggesting the Sangh would put to use its old technique of harnessing communal discord for political mobilisation. And apart from a minor mention in the President’s joint address to Parliament about the Pune techie murder, we haven’t really heard Modi speak on these issues. Perhaps these are relatively too minor for the Prime Minister to intervene. Yet, arguably, this isn’t the political ambience in which the Muslims can be encouraged to “come out of fear politics.” To build such an enabling ambience Modi could or should visit Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, where the grisly communal riotings of last year have disrupted the decades-old amity between the Jats and Muslims. A wedge between the two social groups was further driven because of the BJP’s election campaign. For instance, those accused of fomenting riots were facilitated at a BJP rally which Modi himself addressed. All these could have been described, even though repugnant, as typically the strategy of the BJP to maximize its electoral gains. But the past intruded upon the present on the day one of the accused, Sanjeev Baliyan, was included in the Union Council of Ministers. And to think, the BJP had justifiably joined the chorus for the dropping of Jagdish Tytler from the Congress ministry and the denial of an election ticket to Sajjan Kumar, both alleged to have played a role in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. [caption id=“attachment_1595111” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Representational image: Reuters[/caption] It’s true no charges have been framed against Baliyan, nor has any commission of inquiry indicted him. Nevertheless, his inclusion in Modi’s ministry would dissuade the Muslims to “come out of fear politics.” The Muslim’s tendency to remain in the cocoon of fear will only be reinforced should the BJP appoint Amit Shah, an accused in encounter cases in Gujarat, as party president. Also not inspiring to the community would have been Minority minister Najma Heptullah’s remark that “Muslims are not minorities. Parsis are.” Minority and majority, as we know it, are numerically defined. Perhaps she was indulging in semantics, underlining the fact that 13.4 percent of Muslims in India outstrip the population of even most Islamic countries in real terms. Nevertheless, she forgets that the nomenclature of minority also reflects the distribution of power among social groups. Indeed, Muslims need to be empowered. They are abysmally represented in government services, comprising just 3.31 percent of IAS and 3.66 percent of IPS officers countrywide. On socio-economic indices its status, as the Rajinder Sachar committee report bears out, their lot is no better than that of the Schedules Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Heptullah’s quip could have only fanned the suspicions of Muslims about the Modi government’s agenda. Her recent fulminations against the Maharashtra government for granting 5 percent reservation for Muslims can’t be faulted. The Indian Constitution doesn’t permit preferential treatment on the basis of religion and, anyway, many OBC Muslim social groups are included in both the Central and state lists for reservation. But what is appalling is her refusal to comment on the extension of reservation to Marathas, who dominate Maharashtra’s society in every conceivable way. The philosophy of affirmative action has been systematically turned on its head, in complete violation of the spirit of the Indian Constitution and the Supreme Court pronouncements on the contentious issue. Weeks before the 2014 election, the Jats, as dominant in western Uttar Pradesh as the Marathas are in Maharashtra, were included in the Central OBC list. Not a single party, not even the BJP, opposed the measure. This is precisely the reason why Muslim leaders have taken to demanding religion rather than caste-based reservation, arguing why the Constitutional parameters are strictly adhered to in their case alone. Heptullah’s intervention in the reservation debate will, therefore, be perceived to be an extension of the BJP’s bias against the Muslims. This isn’t to say Muslims shouldn’t emerge out of “fear politics”, particularly of the kind the Congress has mastered. But they do require a particular ambience to feel confident enough to step out of the cocoon they are trapped in. Their fear, Mr Prime Minister, is real and also debilitating. The author is a Delhi-based journalist and can be reached at ashrafajaz3@gmail.com

Representational image: Reuters[/caption] It’s true no charges have been framed against Baliyan, nor has any commission of inquiry indicted him. Nevertheless, his inclusion in Modi’s ministry would dissuade the Muslims to “come out of fear politics.” The Muslim’s tendency to remain in the cocoon of fear will only be reinforced should the BJP appoint Amit Shah, an accused in encounter cases in Gujarat, as party president. Also not inspiring to the community would have been Minority minister Najma Heptullah’s remark that “Muslims are not minorities. Parsis are.” Minority and majority, as we know it, are numerically defined. Perhaps she was indulging in semantics, underlining the fact that 13.4 percent of Muslims in India outstrip the population of even most Islamic countries in real terms. Nevertheless, she forgets that the nomenclature of minority also reflects the distribution of power among social groups. Indeed, Muslims need to be empowered. They are abysmally represented in government services, comprising just 3.31 percent of IAS and 3.66 percent of IPS officers countrywide. On socio-economic indices its status, as the Rajinder Sachar committee report bears out, their lot is no better than that of the Schedules Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Heptullah’s quip could have only fanned the suspicions of Muslims about the Modi government’s agenda. Her recent fulminations against the Maharashtra government for granting 5 percent reservation for Muslims can’t be faulted. The Indian Constitution doesn’t permit preferential treatment on the basis of religion and, anyway, many OBC Muslim social groups are included in both the Central and state lists for reservation. But what is appalling is her refusal to comment on the extension of reservation to Marathas, who dominate Maharashtra’s society in every conceivable way. The philosophy of affirmative action has been systematically turned on its head, in complete violation of the spirit of the Indian Constitution and the Supreme Court pronouncements on the contentious issue. Weeks before the 2014 election, the Jats, as dominant in western Uttar Pradesh as the Marathas are in Maharashtra, were included in the Central OBC list. Not a single party, not even the BJP, opposed the measure. This is precisely the reason why Muslim leaders have taken to demanding religion rather than caste-based reservation, arguing why the Constitutional parameters are strictly adhered to in their case alone. Heptullah’s intervention in the reservation debate will, therefore, be perceived to be an extension of the BJP’s bias against the Muslims. This isn’t to say Muslims shouldn’t emerge out of “fear politics”, particularly of the kind the Congress has mastered. But they do require a particular ambience to feel confident enough to step out of the cocoon they are trapped in. Their fear, Mr Prime Minister, is real and also debilitating. The author is a Delhi-based journalist and can be reached at ashrafajaz3@gmail.com

What Modi must do to end 'fear politics' among India's Muslims

Ajaz Ashraf

• June 30, 2014, 11:58:57 IST

it would seem that Modi, like his party, believes the fear of the Muslim community is unfounded and unreal

Advertisement

)

End of Article