Onions are very much on the minds of politicians as Delhi goes to the polls.

It’s hard to ignore them. The BJP has plastered posters of onions on billboards and bus stands across Delhi to make sure voters remember the sticker shock of the humble pyaaz at Rs 100 a kilo.

That’s got the Congress on the defensive.

[caption id=“attachment_1261987” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  An ad for onions in Delhi[/caption]

At a public meeting attended by Sheila Dikshit near Kashmere Gate, Promila Sibal, wife of union minister Kapil Sibal, protested the BJP was just being a Bahut Jhootha Party for trying to pin the government down on onion prices.

“We’ve had the most rain in years. Inki sarkar hoti toh kya khet mein umbrella lekar khadee hoten? (If it was their government what would they have done? Stood in the fields with umbrellas?)”.

Instead of trying to pass the political hot potato on, Mrs Sibal and co. might have been better prepared if they had been looking at the data being tracked by a company called Premise in far-off San Francisco.

“What’s more surprising than the fact that it was this vegetable that was expressing this volatility was how long it took the press at large to begin reporting on it,” says David Soloff, the co-founder of Premise.

Soloff and his team had noticed the rise of the onion because they’ve been tracking all kinds of prices in India (and other countries) for the last 14 months.

“You see a 250-300 percent spike in just a few months from late spring through late summer and you cannot help but be in awe,” says Soloff. “When you start to see the spillover effects to other products that’s when you really have to pay attention. It’s not just a curiosity.”

That’s why the BJP billboards don’t just have pictures of onions. They have pictures of tomatos as well. And the CSDS/CNN-IBN survey shows that for voters the number one issue by far is mehengai or inflation.

Governments track these kinds of numbers all the time. That’s how they build indicators like a Consumer Price Index. But Soloff says the problem is the way these numbers are collected don’t take into account how much our lives have sped up.

“The nature of our economic lives have sped up. People change jobs quickly. People transact quickly. With one click of a mobile device. They compare prices rapidly. They procure materials in short cycles. There’s micro-pricing.”

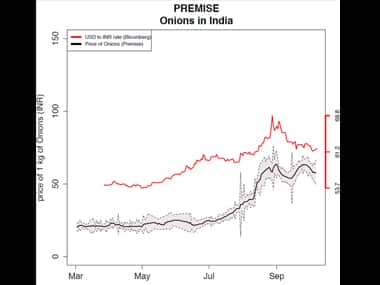

[caption id=“attachment_1262019” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Chart graphing onion price fluctuation.[/caption]

But the data, he says, is still gathered in cumbersome antiquated ways - an elaborate, top-down, centralized model that can take an entire quarter. “There is no way to dynamically adjust what people look at or alter or extend the fields on the fly,” says Soloff. That means by the time the data is scrubbed and the indices computed, reality has moved on. He says, to use a simple analogy, “it’s like looking at last week’s weather.”

Premise tries to do what one of its advisors, Hal Varian, a chief economist at Google calls “nowcasting.” That’s about “predicting the present.”

How they do it is deceptively simple. In Mumbai, Premise initially hired 15 people to go out with their smart phones and capture prices of day to day items across the city for example, milk, eggs, legumes and yes, onions. Soloff calls it a “tracking basket for food inflation.” Premise makes sure it is getting samples from markets of different types from the hypermart to a bus station produce market to a supermarket chain. The trackers get paid per successful data point they capture. But now Premise is experimenting with other ways of compensation as well that makes more sense in a market like India - paying for their data plans and upgrading their phones.

Once Premise has collected enough data, it can create what The Atlantic calls " a blend of Google Street View and the Consumer Price Index." That means Soloff can tell not just that onion prices are going up overall but can burrow down into cities and into neighbourhoods within cities.

He could see that onion prices being sent by his trackers from around the country were moving in “lockstep with the rupee” as the RBI tightened interest rates as the currency plummeted. “As the rupee began strengthening we saw onion prices come up in some cases 30-40 percent in a week or a week and a half,” recalls Soloff. “It was pretty awesome to instrument the real world, to take all this analog and important info and make it accessible in a streaming and digital manner via our workers using the devices they carry with them every day.”

Most importantly, because it’s “nowcasting” it can tell, Soloff says, whether a person selling onions at Rs 120 a kilo somewhere in India is just price gouging because some road is blocked due to unrest or whether it’s the beginning of a real price spike or the distant thunder of an overall inflationary trend in the category.

For Premise the point is not just speed but also the ability to nimbly customize the data. But is there enough data? Soloff admits he needs more customers, a lot more, to be able to expand into second and third tier cities. It can be a sensitive issue. A government might feel Premise is stepping on their turf especially when something like onion prices turns into an election issue even though Soloff sees Premise as “a valid supplier with a lot of government infrastructure” allowing for certain fine-tuning of the blunt instruments governments painstakingly build.

Governments get nervous about numbers like this triggering market panic. But Soloff thinks the reverse is true. “I think the reason it got so out of hand is because people were not broadcasting it,” he says. “The impulse is try and keep the information a secret. Everyone understood and saw it everyday but no one knew when it would stop which provoked further and further anxiety.”

In India, the onion story is an election story. But the larger story around the world is about food inflation. Premise is monitoring the rising prices of meat protein in China. It’s noting that milk prices have been shooting up in Brazil and now affecting packaged dairy and yogurt as well. December 4 will decide the fate of a government in Delhi and the spotlight will shift from onions. But the larger story of food inflation will still continue to be tracked, by young men and women, in cities like Delhi, armed only with older model Samsung phones.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)