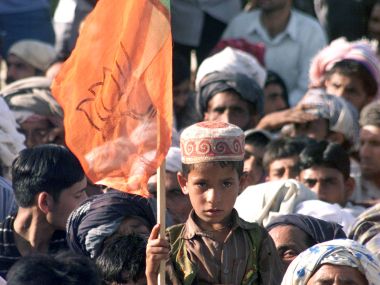

We are looking for beef on Bihar’s election plate. In most places it is missing. In the villages, nobody is interested in beef. Most of the discussions here are vegetarian by virtue of being focussed mainly on chaara (fodder) and its purported thieves and their future. In Sikaria village of Jahanabad, a town once synonymous with Naxalites, a crowd is gradually building up ahead of a political rally. Hundreds of people are sitting on a platform under two huge banyan trees, busy pursuing the favourite pastime of rural Bihar: playing cards and crushing khaini (tobacco) and choona (limestone powder) on their palms. On the campaign trail, it is important to know when a person is ready for a nuanced discussion. But, one of the encouraging cues is when a voter has just pushed khaini in the space between his teeth and lips and is, thus, in a pensive trance. So, we shoot the beef question: Is it an issue in this election? “Beeeef,” snarls an old man wearing a Gandhi topi and lots of Dalit pride in trademark Magahi where the middle syllables are stretched, “is not an issue here. Eee Bihar hai, yahan log khaan-paan par nahin ladta (This is Bihar; here people do not fight over what to eat and drink).” [caption id=“attachment_2464876” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Representative image. Reuters[/caption] The man who talks of Bihar in the manner of Leonidis talking about this being Sparta, is a 77-year-old Raghuvar Prasad Paswan. In 1956, he was the first Dalit to have passed out of the Sikaria government school, set up in 1944, in his entire village. He has been witness to an era when people of his community were not even allowed to sit on a charpoy in the company of people of upper castes. “In Bihar the fight is always against Dalit oppression by upper castes. Here Mandal (caste divide) is more powerful than kamandal (communal division),” says Paswan. There is merit in Paswan’s argument. Bihar’s political history suggests that unlike other north Indian states, a straight-down-the-middle communal polarisation has never succeeded in smudging the horizontal divisions on caste lines. The prime example is the 1991 Lok Sabha election. A few months before the polls, Lalu Prasad Yadav arrested LK Advani on entering Bihar with his rath yatra for Ram temple in Ayodhya. In other states, a sharp communal polarisation helped BJP dominate elections. But in Bihar, the BJP remained a marginal force winning just a handful of seats. Bodhgaya is another instance of Bihar’s inherent liberal attitude. In many other ‘holy’ cities of north Indian states, Pushkar and Ujjain for instance, eating and sale of meat (even alcohol) is completely banned in deference to the religious importance of these places. But in Gaya and adjoining Bodhgaya, no such symbolic measures in place and poultry and meat are freely available, just metres away from temples and religious shrines. Muzaffar Husain ‘Rahi’, is a self-proclaimed disciple of Karpoori Thakur, the former Bihar CM he now calls a “mahamanav” (great man). Rahi is now chief of the Jahanabad unit of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s party. “Beef is a good issue for TV channels and media. But here we have other things to worry about. Our fight is against the existing system. We will accept things have changed when a Dalit will have equal opportunities of becoming a priest in India and an uneducated Brahmin will not be considered more eligible in spite of his incompetence.” The villagers argue that by raising the issue of beef in politics, the BJP has shown lack of knowledge of rural economics. When a cow gets old or sick, its owner sells it to an abattoir. This helps the owner raise money. And when the animals dies, Dalits skin it for the leather industry. A dead cow is worth nothing in a village. In his column for The Sunday Times,

Swaminathan S Aiyar says the BJP may have shot itself in the foot by turning beef into a poll issue. He argues that the BJP’s stand is a classic example of the calamitous combination of bad politics and bad economics. It is apparent that more than beef, sustained allegations of corruption (chaara chori) and lawlessness (jungle raj) in the Lalu Yadav-era could help the BJP more in stopping Dalits and backward classes from voting against the Nitish-led alliance. But, beef is still high on the BJP menu. At an election rally in Samastipur on Saturday, Amit Shah first leans on casteism and then on cows. He wonders what sort of gau-palak is Lalu Yadav to not know the difference between gau ka maas and bakre ka maas (beef meat and goat meat). The BJP is still feeling the impact of RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s call for a review of reservation on the poll turf. So, it is trying to counter Mandal with kamandal. In this bedlam, the media has stepped up to bear the burden of keeping beef alive as an election issue. At a press conference in Patna on Saturday, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar is exhorting the media to expose the “baseless allegations” against his government by the BJP leaders. “Hit and run, bumper publicity,” Kumar says several times to argue that the BJP is just throwing charges and running away from debate. He reels out a litany of counterarguments and figures to support his claim. Sample one: “The PM says there have been 4000 kidnappings for ransom in Bihar. But the crime date records show the number is just 40, and even among these all but one victim was released or rescued.” But the posse of media has just one question for him after an hour-long conference. “Sir, what is your opinion on beef? Should people be allowed to eat it?” Kumar replies: “First you tell me whether you should be wearing a green or a blue shirt?” The media too, maybe, needs some food for thought. Khaini under a banyan tree could perhaps aid introspection.

Representative image. Reuters[/caption] The man who talks of Bihar in the manner of Leonidis talking about this being Sparta, is a 77-year-old Raghuvar Prasad Paswan. In 1956, he was the first Dalit to have passed out of the Sikaria government school, set up in 1944, in his entire village. He has been witness to an era when people of his community were not even allowed to sit on a charpoy in the company of people of upper castes. “In Bihar the fight is always against Dalit oppression by upper castes. Here Mandal (caste divide) is more powerful than kamandal (communal division),” says Paswan. There is merit in Paswan’s argument. Bihar’s political history suggests that unlike other north Indian states, a straight-down-the-middle communal polarisation has never succeeded in smudging the horizontal divisions on caste lines. The prime example is the 1991 Lok Sabha election. A few months before the polls, Lalu Prasad Yadav arrested LK Advani on entering Bihar with his rath yatra for Ram temple in Ayodhya. In other states, a sharp communal polarisation helped BJP dominate elections. But in Bihar, the BJP remained a marginal force winning just a handful of seats. Bodhgaya is another instance of Bihar’s inherent liberal attitude. In many other ‘holy’ cities of north Indian states, Pushkar and Ujjain for instance, eating and sale of meat (even alcohol) is completely banned in deference to the religious importance of these places. But in Gaya and adjoining Bodhgaya, no such symbolic measures in place and poultry and meat are freely available, just metres away from temples and religious shrines. Muzaffar Husain ‘Rahi’, is a self-proclaimed disciple of Karpoori Thakur, the former Bihar CM he now calls a “mahamanav” (great man). Rahi is now chief of the Jahanabad unit of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s party. “Beef is a good issue for TV channels and media. But here we have other things to worry about. Our fight is against the existing system. We will accept things have changed when a Dalit will have equal opportunities of becoming a priest in India and an uneducated Brahmin will not be considered more eligible in spite of his incompetence.” The villagers argue that by raising the issue of beef in politics, the BJP has shown lack of knowledge of rural economics. When a cow gets old or sick, its owner sells it to an abattoir. This helps the owner raise money. And when the animals dies, Dalits skin it for the leather industry. A dead cow is worth nothing in a village. In his column for The Sunday Times,

Swaminathan S Aiyar says the BJP may have shot itself in the foot by turning beef into a poll issue. He argues that the BJP’s stand is a classic example of the calamitous combination of bad politics and bad economics. It is apparent that more than beef, sustained allegations of corruption (chaara chori) and lawlessness (jungle raj) in the Lalu Yadav-era could help the BJP more in stopping Dalits and backward classes from voting against the Nitish-led alliance. But, beef is still high on the BJP menu. At an election rally in Samastipur on Saturday, Amit Shah first leans on casteism and then on cows. He wonders what sort of gau-palak is Lalu Yadav to not know the difference between gau ka maas and bakre ka maas (beef meat and goat meat). The BJP is still feeling the impact of RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s call for a review of reservation on the poll turf. So, it is trying to counter Mandal with kamandal. In this bedlam, the media has stepped up to bear the burden of keeping beef alive as an election issue. At a press conference in Patna on Saturday, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar is exhorting the media to expose the “baseless allegations” against his government by the BJP leaders. “Hit and run, bumper publicity,” Kumar says several times to argue that the BJP is just throwing charges and running away from debate. He reels out a litany of counterarguments and figures to support his claim. Sample one: “The PM says there have been 4000 kidnappings for ransom in Bihar. But the crime date records show the number is just 40, and even among these all but one victim was released or rescued.” But the posse of media has just one question for him after an hour-long conference. “Sir, what is your opinion on beef? Should people be allowed to eat it?” Kumar replies: “First you tell me whether you should be wearing a green or a blue shirt?” The media too, maybe, needs some food for thought. Khaini under a banyan tree could perhaps aid introspection.

Ruckus over beef won't work in Bihar polls: BJP may have shot itself in the foot

Sandipan Sharma

• October 12, 2015, 12:16:51 IST

Bihar’s political history suggests that unlike other north Indian states, a straight-down-the-middle communal polarisation has never succeeded in smudging the horizontal divisions on caste lines.

Advertisement

)

End of Article