The current session of Parliament is paralysed, thanks to the growing solidarity among the opposition parties to embarrass the Narendra Modi government over its decision to demonetise old notes of Rs 1,000 and Rs 500. And all of this in the name of the “common men” who have been forced to stand in long queues in front of banks and ATMs to exchange old notes and withdraw their “own money". And yet, one is not exactly clear as to what does the opposition protests hope to gain by disrupting the proceedings in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. There is so much galimatias emanating from the opposition parties on the issue. While the Trinamul Congress and Aam Admi Party want total withdrawal of the government’s decision, the rest of the opposition hasn’t been very forthcoming on this demand. Janata Dal (U)’s supreme leader and Bihar Chief minister, Nitish Kumar, has supported the Modi government’s action, but in the Parliament, party leader Sharad Yadav is in full support of the Congress, Left parties and the Bahujan Samaj Party. [caption id=“attachment_3120124” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] A scene in the Rajya Sabha during the winter session, in New Delhi on Tuesday. PTI[/caption] In the Rajya Sabha, the Congress forced a general discussion on the subject on the opening day of the session itself, but the next day it changed its stance to join other opposition parties that no more debate would be allowed until the House passed a condolence “over the death of 70 people” because of the lack of cash, though none of the opposition leaders could reply to the Deputy Chairperson’s query on the authenticity of the death-figure. On Tuesday, the opposition’s goal in Rajya Sabha changed further to ensure the presence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the House before the debate on the subject resumed. Interestingly, while the stalled debate on demonetisation is without any voting and censure in the Rajya Sabha, the Congress is demanding a debate on the same subject in the Lok Sabha with provisions for voting and censure. The opposition’s tactics remind us of the proceedings in the 15th Lok Sabha (2009-2014). It may be noted that the 15th Lok Sabha was the least productive Lok Sabha ever as 40 percent of its total time was lost to disruptions. That time, the BJP was in opposition and the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) was in power. Now, the situation has reversed, but the trend continues. After 2014, the opposition, particularly the Congress, has stalled the 16th Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha on several issues including the roles of External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje in helping fugitive businessman Lalit Modi, the alleged involvement of Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Chauhan in recruitments-scam (popular known as the Vyapam scam), the controversial statements emanating from the ruling party members on communal and caste violence (Dadri-lynching and beef politics), the “vindictive policy” of the Modi government against Sonia and Rahul Gandhi in the “National Herald case”, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) Bill and now the issue of demonetisation of old Rs 500 and Rs 1,00 notes. It is worth noting that when the Parliament is in session, it costs the national exchequer Rs 2.5 lakh every minute. I am not one of those to buy the argument that the Congress is doing exactly what the BJP did during the UPA regime. Two wrongs cannot make a right. And to accept that argument would be to imply that if tomorrow the Congress regains power, the BJP should be allowed to paralyse the Parliament. Also, it would mean that until and unless a party or a ruling coalition has a majority in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, nothing concrete will move forward in the country. Nothing can be more perverse than the argument like this. Maintaining discipline, decorum and dignity of the Parliament is of paramount importance for the Indian democracy. These principles mattered a lot in the initial years of the Indian Parliament. So much so that in February 1963, when during the President’s address to a joint session of the Parliament some of the MPs heckled the speech for being in English instead of Hindi. One Rajya Sabha member even walked out. However, the next day, members — cutting across party lines — condemned the heckling and expressed their regrets in solidarity. In a letter to the Chief Ministers (18 February 1963), Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru described the incident as “the first of its kind in Parliament” and “most regrettable”. He added, “It is clear that this kind of thing has to be met effectively; otherwise the work of our Parliament and Assemblies would be made difficult and brought into disrepute. This is a vital matter and I hope the Parliament will set a good example which will be followed in the State Assemblies." I wonder whether Sonia Gandhi, who always points out the glorious “history” of the Congress and particularly of her family, should also be particular of what Nehru said and wrote. One also remembers how on a lesser misbehaviour by today’s standards, the then Chairman of the Rajya Sabha Dr S Radhakrishnan had expunged certain portions of the speech of a member and had remarked (27 September 1955): “We want to maintain the good name and dignity of this House. Every one of us is interested in that as much as I am. I do not want it to be said that sometimes these discussions suggest that we are not behaving like serious, responsible Members of Parliament but rather like irresponsible professional agitators. That impression even all members of this House to whatever side they may belong should avoid. We must be careful and preserve our good name and our dignity. That is what I am anxious about." [caption id=“attachment_3120126” align=“alignright” width=“380”]

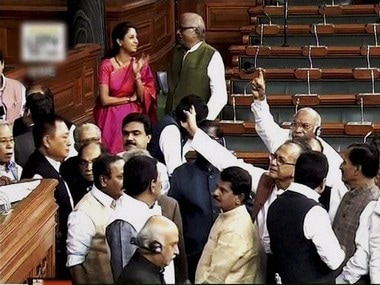

Opposition members protest in the well of Lok Sabha during the winter session of Parliament in New Delhi on Monday. PTI[/caption] Interestingly, one important aspect that needs to be noted here is the fact that the contentious debates between the government and opposition over the years have been mostly around areas pertaining to political and administrative spheres of the governance and not on economic and social issues such as reservations, nationalisation of banks and other properties. One may, of course, argue that there have been differences of views in the Parliament over globalisation and liberalisation of the economy. However, these differences have emerged essentially not out of conviction but out of political expediencies. We have a plethora of examples when opposition parties (BJP in the past too) attacked the government in Parliament for surrendering the economic sovereignty at the altar of globalisation, but their respective governments in various states do exactly the same. The overemphasis on politics in Indian Parliament could be attributed to the phenomenon of the promotion and consolidation of personalised and factional identities. We are today in an age of “agitational politics”, whose characteristic feature is the decline of the Congress as a national party and the growth of regional and family-oriented parties whose leaders have been the products of what late political scientist Rajni Kothari called “secularisation of castes” and the rise of lower peasantry in various states. These parties have been the inevitable products of the expansion of India’s political base and the opening of political space for the marginalised sections of the society. Their leaders are not enthused by the so-called all-India outlook. So much so that except in a handful of states such as Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan where the Congress and BJP are the principal rivals, Indian politics has undergone complete regionalisation. In almost all the states, the regional players are as important, if not more than, as the two national parties. It is true that opposition in India has always been fragmented. But the difference between then and now is that there is no systematic constraint for the growth of the opposition. There is no more a system of one-party dominance (of the Congress) that helped the dominant party to develop a remarkable capacity to articulate opposition inputs. This, in turn, reflects in their parliamentary behaviours. If in the past “opposing the government” was the catchphrase, nowadays it’s “obstructing the government by any means”. An effective opposition, while opposing various acts of omission and commission of the government, acts responsibly and suggests remedies and alternatives. It is not the business of the opposition to oppose just for the sake of opposition. But that is precisely what one is witnessing these days. That being the case, is there a way out of the frequent parliamentary logjams? In my considered opinion, the presiding officers of the Parliament (Vice President and Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha; Speaker and Deputy Speaker of the Lok Sabha) must play a proactive role in taking the support of the Government and majority of the members to restore people’s confidence in the Parliament. They have to exercise their power inherent in the Rules and Procedures of the Parliamentary Practices and take exemplary actions against the members who deliberately create disturbances in the functioning of the Parliament by ignoring or disobeying the chair. After all, in the past, members resorting to misconduct have been asked by the chair to withdraw from the House (The chair can “name” or request the sergeant-at-arms to remove the disturbing member) and in many cases, members have been suspended for misbehaviour. At present, more than the Speaker, it is the Chairman/Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha who must apply the existing rules strictly, because, more than the Lok Sabha, it is the Rajya Sabha that is bringing the legislative business of the country to a grinding halt. And that too when under the “Rules of Conduct and Parliamentary Etiquette” of the Rajya Sabha, “the House has the right to punish its members for their misconduct whether in the House or outside it. In cases of misconduct or contempt committed by its members, the House can impose a punishment in the form of admonition, reprimand, and withdrawal from the House, suspension from the service of the House, imprisonment and expulsion from the House.”

Opposition members protest in the well of Lok Sabha during the winter session of Parliament in New Delhi on Monday. PTI[/caption] Interestingly, one important aspect that needs to be noted here is the fact that the contentious debates between the government and opposition over the years have been mostly around areas pertaining to political and administrative spheres of the governance and not on economic and social issues such as reservations, nationalisation of banks and other properties. One may, of course, argue that there have been differences of views in the Parliament over globalisation and liberalisation of the economy. However, these differences have emerged essentially not out of conviction but out of political expediencies. We have a plethora of examples when opposition parties (BJP in the past too) attacked the government in Parliament for surrendering the economic sovereignty at the altar of globalisation, but their respective governments in various states do exactly the same. The overemphasis on politics in Indian Parliament could be attributed to the phenomenon of the promotion and consolidation of personalised and factional identities. We are today in an age of “agitational politics”, whose characteristic feature is the decline of the Congress as a national party and the growth of regional and family-oriented parties whose leaders have been the products of what late political scientist Rajni Kothari called “secularisation of castes” and the rise of lower peasantry in various states. These parties have been the inevitable products of the expansion of India’s political base and the opening of political space for the marginalised sections of the society. Their leaders are not enthused by the so-called all-India outlook. So much so that except in a handful of states such as Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan where the Congress and BJP are the principal rivals, Indian politics has undergone complete regionalisation. In almost all the states, the regional players are as important, if not more than, as the two national parties. It is true that opposition in India has always been fragmented. But the difference between then and now is that there is no systematic constraint for the growth of the opposition. There is no more a system of one-party dominance (of the Congress) that helped the dominant party to develop a remarkable capacity to articulate opposition inputs. This, in turn, reflects in their parliamentary behaviours. If in the past “opposing the government” was the catchphrase, nowadays it’s “obstructing the government by any means”. An effective opposition, while opposing various acts of omission and commission of the government, acts responsibly and suggests remedies and alternatives. It is not the business of the opposition to oppose just for the sake of opposition. But that is precisely what one is witnessing these days. That being the case, is there a way out of the frequent parliamentary logjams? In my considered opinion, the presiding officers of the Parliament (Vice President and Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha; Speaker and Deputy Speaker of the Lok Sabha) must play a proactive role in taking the support of the Government and majority of the members to restore people’s confidence in the Parliament. They have to exercise their power inherent in the Rules and Procedures of the Parliamentary Practices and take exemplary actions against the members who deliberately create disturbances in the functioning of the Parliament by ignoring or disobeying the chair. After all, in the past, members resorting to misconduct have been asked by the chair to withdraw from the House (The chair can “name” or request the sergeant-at-arms to remove the disturbing member) and in many cases, members have been suspended for misbehaviour. At present, more than the Speaker, it is the Chairman/Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha who must apply the existing rules strictly, because, more than the Lok Sabha, it is the Rajya Sabha that is bringing the legislative business of the country to a grinding halt. And that too when under the “Rules of Conduct and Parliamentary Etiquette” of the Rajya Sabha, “the House has the right to punish its members for their misconduct whether in the House or outside it. In cases of misconduct or contempt committed by its members, the House can impose a punishment in the form of admonition, reprimand, and withdrawal from the House, suspension from the service of the House, imprisonment and expulsion from the House.”

Maintaining the discipline, decorum and dignity of the Parliament is of paramount importance for the Indian democracy, something our politicians seem to have forgotten

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)