There has been, in India, a recent outbreak of statue-toppling and defacement, with examples popping up from various parts of the country. Statues of figures revered by the Left, the Right and backward caste groups all suffered injury. In keeping with contemporary Indian culture, there has been a huge brouhaha over this, especially on television and Twitter. The whole thing started, as readers may recall, with the BJP winning a famous victory over the CPI (M) in faraway Tripura. Some enthusiasts celebrated this occasion by pulling down a 5-feet tall fibreglass statue of Communist deity Vladimir Lenin off its pedestal with the aid of a bulldozer. Images of this act were captured on recording devices, and, as is the culture nowadays, shared widely on social media, thus enabling everyone and their cat to have a great time outraging for or against the toppling of statues. [caption id=“attachment_4409351” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  (L) Lenin statue being toppled in Belonia, Tripura. (R) CPI(M) leaders protest the razing of the statue at a Kolkata rally. File Photo/PTI[/caption] Culture, both as way of life and as artefact, is perennially in the process of being erased and created anew. The gradual erasure is not as dramatic as the deliberate pulling down of a statue, but in the long run, it is usually far more effective.

The most complete erasures of culture are not the ones we fight. They are the ones we embrace or surrender to.

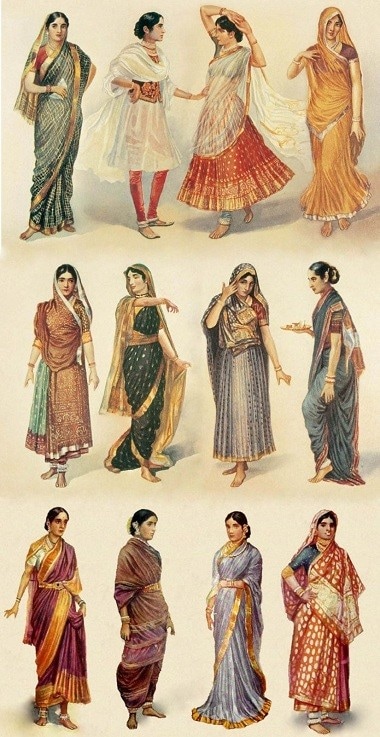

Our culture today generally includes a hefty dose of social media, YouTube and Netflix. Many of our interactions including some of our most intimate ones are mediated by apps, none of which existed at the turn of the millennium in 2000. That vital artefact of culture, the printed book, is, like the printed newspaper and magazine, facing some hard existential questions. A wonderful cultural tradition, the theatre, to which so many great dramatists down the ages from around the globe brought glory, is now a relic of times gone by. Portrait and landscape painting, once practised by master painters such as Leonardo da Vinci, is now history — we are all photographers now in the Age of the Selfie. Sculpture, which by 1917 had already made the journey from Michelangelo to Marcel Duchamp, has since progressed — if that is the word — to stuffed animals. If you look at global cultural diversity now compared to 100 years ago, it has decreased measurably. At least 200 languages have become extinct in the past century. The pace of language extinction is only increasing by the day. Experts reckon that almost half the world’s 6,900 languages are now endangered. Each language that dies takes with it a culture. There are many elements to each — food, clothes, artefacts, ways of living in and thinking about our shared world. They are, to quote the anthropologist Wade Davis, “unique manifestations of the human spirit”. Their loss leaves all of us poorer. Most of us know vaguely that this sort of thing is happening, and has been for a while. For example, there was a famous book and film called The Last of the Mohicans, about a Red Indian tribe from what is now New York. The Mohicans are not quite extinct, but their language is dead and there are around 3,000 of them left in a reservation in Wisconsin, USA. This is a fate similar to that suffered by Native American tribes in general, across America. It is better than the plight of the Aboriginals of Australia, who were not counted in human population censuses until 1967. Aboriginal affairs were handled, in some parts of Australia, by departments that also looked after fauna. It was all a part of successful colonisation that wiped out not just the indigenous cultures but the indigenous people as well. [caption id=“attachment_4409347” align=“alignright” width=“380”]  Sari styles in India. Image via Wikimedia Commons[/caption] Today, the trend towards cultural erasure has not ended. Look at old photos of your great-grandparents. Chances are they dressed in their own distinctive local ways. Their sartorial cultures supported an immense diversity of handicrafts. In India, just the range of saris was incredible — and the sari is only one example. Pretty much every tribe in Northeast India, who don’t traditionally wear saris, have their own textile traditions and styles of dress. There were 220 languages spoken in Northeast India alone so the diversity was considerable. That diversity of dress has now been largely flattened into a global homogeneity. The process is ongoing. Handicraft traditions around the world, including in India, are struggling to survive. Crafts that developed over centuries are dying out. There is no outrage over it; it is not as exciting as a statue being toppled. To some extent, this silent erasure is the accumulated result of many individuals making free choices. For instance, the Nagas can go back to their traditional outfits if they wish, but it is unlikely that many would want to do so. The young chaps who dress up in loincloths and feathers during the touristy Hornbill Festival in Kohima probably wear branded jeans and tees the rest of the time. Even the most rabid supporters of tradition among them have given up the loincloth, and old customs such as headhunting. The community’s departure from headhunting accompanied its conversion to Christianity. As a result, elements of the old traditional faith, to which cultural products such as beautifully carved wooden figurines and the horned houses of the Angami Nagas were linked, have gradually wasted away. The old gods had now become associated with evil. This is of course only a recent example of an ancient global phenomenon. We no longer see statues of the old Greek or Roman gods except in select museums for the same reason. The Egyptians don’t carve statues of Isis and Osiris or build pyramids any more. Their men don’t wear the belted skirts called ‘shendyt’ and their women don’t sport elegant dresses called ‘kalasiris’. Like the Persians of today, they generally wear burqas; the contest for the future is between the burqa and the skirt. The classical cultures of ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt and Persia, like those of Afghanistan and Pakistan — remember the Bamiyan Buddhas — have all suffered erasure. Bonfire of the vanities The most popular of all elements of culture is arguably cuisine. Most people like their own home cuisines, and often, they like a lot of other foods as well. The popularity of what passes for Chinese food in India, and Indian food in the West, is testimony to the fact that people by and large like the diversity of cuisines the modern marketplace offers. There is however a tussle between vegetarians and those who eat fish and meat, over what should be eaten. Even among people who eat meat, certain kinds of meat are considered off-limits. Pork is forbidden to Muslims and beef to Hindus. However neither the average Hindu nor the average Muslim would eat dog meat, which was traditionally a delicacy in China, Korea and parts of Northeast India. Cultural erasure also includes the deletion of the dog curry recipe from the favourites’ list.

The arguments and fights that we have seen in the past few years in this country about cultural erasure fail to take into account its many morally ambiguous dimensions. What we see instead are reactionary political pronouncements voiced by acolytes of one party or another. The battles are really about today’s politics, not yesterday’s culture. They are about the BJP, Congress, CPI(M) or other aspirants for political power.

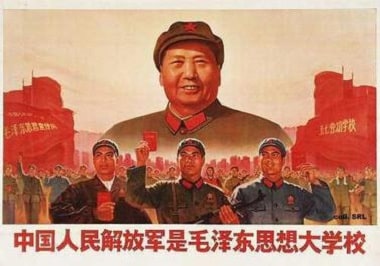

This too is as it has long been, everywhere. [caption id=“attachment_4409349” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Poster for Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China. Image via Wikimedia Commons[/caption] Few cities on earth have as much art as Florence. Yet what remains there today is only what survived the infamous “bonfire of the vanities”, a burning of clothes, books, manuscripts, paintings, sculptures, and more, organised in 1497 by a powerful Dominican friar named Savonarola. Politics was involved both in his action and in his eventual fate: Savonarola, who had become the de facto ruler of Florence, was hanged to death on the Pope’s orders a year later. In France, the French Revolution was accompanied by large-scale destruction of buildings, monuments and statues from the country’s regal past. There are sketches of some of these in the Louvre. You can see, for instance, a sketch of the destruction of a famous bronze statue of King Louis XIV on horseback, which was erected in 1699, being smashed with sledgehammers in 1792. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia under Lenin knocked down monuments to that country’s tsarist past, and demolished grand old churches, since religion had been decreed the opium of the masses. China did even better. Under Mao Zedong, the country had a revolution specially dedicated to the destruction of culture, called, naturally, the Cultural Revolution. Its aims were to erase the “four olds”, these evils being old customs, old culture, old habits and old thinking. For a period of a decade starting 1966, Chairman Mao’s Red Guards went around China enthusiastically destroying its ancient heritage. Even the grave of Confucius did not escape desecration. The real reason behind the iconoclasm and vandalism, in each of these cases, was contemporary power struggles. In India, which has seen its share of cultural erasure over the centuries, the BJP and its supporters allege the destruction of numerous temples by Muslim kings during medieval times. Of these, none is as controversial as the alleged destruction of a Ram Temple in Ayodhya by the Mughal king Babur. A mosque built there on his orders in 1529 was destroyed by mobs organised and led by BJP and Vishwa Hindu Parishad leaders more than 450 years later in 1992. The logic offered by its supporters for that act of destruction, and for the ongoing demand for construction of a grand Rama temple at the site, is that it would set right a historical wrong. The Hindus had suffered centuries of humiliation at the hands of invading Muslims, of which the Babri Masjid was a symbol, the argument goes. Therefore it deserved to be torn down and replaced. The logic of righting historical wrongs is one that finds favour on all sides of the political divide. It is used by religious, linguistic, caste and gender groups to argue for reparations now in lieu of past persecutions. Of course, it takes a certain amount of power in the now to be able to extract any reparations; the powerless by definition have no power. The logic of righting historical wrongs is therefore a route to power for currently ascendant groups. The basis of justice, which is related to deliberate acts by individuals rather than communities, goes for a toss. Entire communities are expected to pay for actions ascribed to their ancestors, like unborn children will pay for ours.

It seems to be a part of most cultures to want to impose their present power on the past, and build structures that may in name be dedicated to some religious or secular deity, but are in fact monuments to their own currently mighty and glorious selves.

Thus in India numerous statues of figures such as Ambedkar, Bose, Gandhi, Sardar Patel and Shivaji, almost universally of poor artistic merit and intrinsic value — none of them is Michelangelo’s David or a Chola bronze Nataraja — continue to be built. No one except the ubiquitous pigeons has any use for them on most days…but once or twice a year, the statues are spruced up and the politicians who derive power from them come to garland them and be photographed doing so. The fate of those statues, like that of the garlanding netas, will depend on the vicissitudes of political power. In the long run, they will all die, politicians and statues alike. The bonfire of all such vanities is what the poet Percy Shelley narrated in his poem Ozymandias: I met a traveller from an antique land, Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand, Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal, these words appear: My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away. The writer, an author and essayist, is the former editor of newspapers in Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru. He tweets @MrSamratX

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)