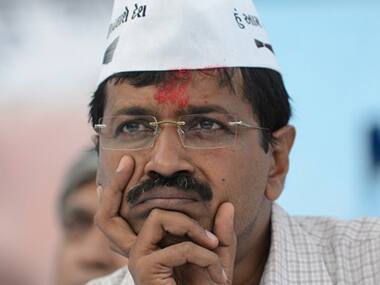

Arvind Kejriwal has a problem: He acts first, thinks later and regrets forever. For some incomprehensible reason, the Delhi chief minister needs a liberal dose of hindsight, a smackdown in public to do exactly what he should have done at the very beginning. Unfortunately, Kejriwal has turned into a live example of that famous Hindi song: Sab kuch luta ke hosh mein aaye to kya hua. He has become a chronic patient of post-facto common sense. His obduracy and pig-headed tenacity in waging a needless war on Jitendra Singh Tomar and then capitulating after being left with no other option is a classic example of his calamitous syndrome. [caption id=“attachment_2288966” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  AFP image[/caption] Late on Tuesday night, Kejriwal finally sought Tomar’s resignation, a decision he could have taken when his law minister was accused of fabricating academic qualifications. Several months ago, when controversy over Tomar’s degrees erupted, Kejriwal could have retained his halo by asking the minister to step down till he was absolved of the charges. Had he done this, Kejriwal could have emerged as a leader who prefers morality over loyalty, the proverbial Caesar’s Wife over a controversial crony. But Kejriwal missed the opportunity and let Tomar cling on to the post. He stuck to the suicidal policy of fighting a war with an Achilles Heel. Now, the barbs and arrows to the usual soft spot are hurting him. In Vishal Bhardwaj’s Omkara, Langda Tyagi delivers a memorable line. “Bewakoof (a foolish person) aur moron (civilized translation of the cuss word he uses) mein dhaage bhar ka fark hota hai.” Somehow Kejriwal always manages to cross this thread. Kejriwal’s career is full of moves inspired by the fidayeen ideology, of do-or-die battles. But in the end most of them lead to the same denouement: heavy political damage that forces him to scoot with his tail between the legs. His disastrous U-turns can cover the syllabus for a course on how not to act in haste and regret at leisure. Chapter one: the dharna on Delhi roads as CM (result: a face-saving compromise). Chapter two: The decision to discontinue janata darbars (after fleeing to safety due to fear of a stampede). Chapter three: The eagerness to quit the CM’s chair (result: he apologised profusely). Chapter four: The decision to fight Lok Sabha polls (result: he almost perished). Nothing helps him learn. A year ago, Kejriwal spent a few days in Tihar because he refused to furnish a bail bond in the defamation case filed by Nitin Gadkari. His initial stand could have been construed as moral and legitimate, but he himself buckled after a few days and chose discreet compromise over valour by agreeing to diligently listen to the court after being humiliated. What makes Kejriwal a pathological fighter who ultimately surrenders? His estranged colleague and sociologist Professor Anand Kumar thinks the Delhi CM has some deep-seated personality issues. “He is certainly a deeply insecure person who needs psychological care and emotional help to shed the baggage of anxieties, apprehension and baseless fears,” Kumar argued in an interview. I would pick up one of his favourite words to explain the problem: ahankar. Kejriwal seems to be full of self-belief bordering on arrogance; he seems to think that he is always right by virtue of being intellectually and morally superior to others. He exhibited these classical signs of ahankar when he defended Tomar by claiming that he was personally satisfied with the law minister’s reply to allegations of fake degrees, implying his word was gospel, vox dei. Similarly, when he wanted to get rid of Yogendra Yadav and Prashant Bhushan, he based his case on the fact that it had become impossible for HIM to work with them. One of the defining features of such people is that they need constant endorsement of their superiority. They do this by blaming others for their failure (others advised him to quit and rush into Parliamentary polls, he claims), taking credit for success, surrounding themselves with fawning fools, mediocre advisors and sycophants—generally people who make them look great in comparison—and throwing out anybody who could be a challenge. The biggest problem with vacuous pride, however, is that it doesn’t allow you to live in peace with a setback. The sense of hurt makes you yearn for redemption, an opportunity to get up again, fight another battle and, this time, win it. Sadly, it leads to an unending spiral. A quick analysis of his past will tell us how many of these traits define Kejriwal. And why he is always on the verge of yet another battle and surrender.

Arvind Kejriwal has a problem: He acts first, thinks later and regrets forever.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)