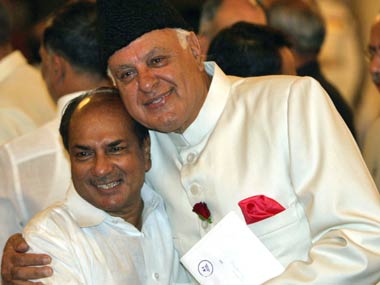

On Jammu and Kashmir, we seem to be barking up the wrong tree again. The presumption that the developments post August 1953 left an indelible mark on the collective consciousness of a troubled state and set the stage for the progressive alienation of Kashmiris from India, is too sweeping in the first place. And then going 58 years back in time to rearrange the pieces to fix the Kashmir problem looks impractical. Sheikh Abdullah, the popular National Conference leader and friend-turned-foe of then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was arrested and put in prison for 11 years on 9 August, 1953 – with a small interval in 1958 – in the Kashmir Conspiracy Case. In a series of constitutional amendments and executive orders after that the Centre curtailed the state’s autonomy and expanded the sphere of its authority over J&K. The major political parties of the state – the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) –have been intermittently insisting on reverting to the pre-1953 status as a major step towards resolving the Kashmir imbroglio. Prior to 1953, the J&K government had exclusive jurisdiction over all departments, barring defence, foreign affairs and communications. An agreement signed between the state government and New Delhi in 1952 had provided other safeguards ensuring the special autonomous status for the state within the Indian Union. The BJP and the Congress, the major parties in the country, are opposed to the idea. Both are unwilling, though in different degrees, to let the state have more autonomy than what it already has. The debate is back again. According to a report in Hindustan Times, the Central interlocutors on J&K are contemplating making a recommendation to the Centre, asking it to revert to the pre-1953 status. Quoting sources close to interlocutors, the newspaper said the three-member team would propose an amendment in the Constitution to reverse whatever changes have taken place in the post-1953 decades. However, the interlocutors, who were appointed late last year to initiate dialogue with people of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh, have denied planning any such recommendation. [caption id=“attachment_75975” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“India’s Defence Minister A. K. Antony is hugged by the patron of the National Conference Farooq Abdullah. Reuters”]

[/caption] Such move could be ill-advised. The presumption excludes the fact that much of the alienation could be due to the dissatisfaction with the chief ministership of Farooq Abdullah after 1982, bureaucratic indifference and poor governance. It also ignores that the post-1989 spurt in insurgency could be due to the largely discredited elections of 1987, which many believe was rigged to favour the National Conference-Congress alliance. It does not take into account the heightened support from Pakistan’s agencies for militant and other activities aimed at fomenting instability. But the more important question here is whether the efforts at resolving the J&K issue should focus more on the ideas of integration – aspects which bring the state closer to the rest of India– or keep dwelling on separation – elements that ensure that the gap between both remains how it is. In the 58 years since Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest, the world has changed a lot. There are more factors around to bind the Kashmiris to India than earlier, interaction at different levels has gone up. The `recommendation’ would entail reversing these: the presidential promulgation of 1954, extending all provisions of the Constitution to the state; status of J&K as one of the constituent states of India; and officers of the all-India services. The result could be further isolation of the state from the national mainstream and gradual de-linking of contact at the administrative level. It is dangerous, both for the state and the country. Continues on the next page Former governor of J&K, Jagmohan, said, “After 1953, various sections of governance were integrated with Jammu and Kashmir. If the state is provided with autonomy of the pre-1953 status, who will fund the government, how will people get their salaries and who will audit the accounts.” He added that the demand for autonomy was the charter of the state’s disintegration from India. Moreover, all the powers –legislative, executive and judicial–would be conferred on the council of ministers depriving the Kashmiris of political rights. The idea of devolution of powers is alright but autonomy is dangerous. The recommendation also overlooks the possibility of economic integration of the state with India and the opportunities for the Kashmiris there of. On Jammu and Kashmir, we seem to be barking up the wrong tree again. The presumption that the developments post August 1953 left an indelible mark on the collective consciousness of a troubled state and set the stage for the progressive alienation of Kashmiris from India, is too sweeping in the first place. And then going back 58 years back in time to rearrange the pieces to fix the Kashmir problem looks impractical. Sheikh Abdullah, the popular National Conference leader and friend-turned-foe of then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was arrested and put in prison for 11 years on August 9, 1953 – with a small interval in 1958 – in the Kashmir Conspiracy Case. In a series of constitutional amendments and executive orders after that the Centre curtailed the state’s autonomy and expanded the sphere of its authority over J&K. The major political parties of the state – the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) – have been intermittently insisting on reverting to the pre-1953 status as a major step towards resolving the Kashmir imbroglio. Prior to 1953, the J&K government had exclusive jurisdiction over all departments, barring defence, foreign affairs and communications. An agreement signed between the state government and New Delhi in 1952 had provided other safeguards ensuring the special autonomous status for the state within the Indian Union. The BJP and the Congress, the major parties in the country, are opposed to the idea. Both are unwilling, though in different degrees, to let the state have more autonomy than what it already has. The debate is back again. According to a report in The Hindustan Times, the Central interlocutors on J&K are contemplating making a recommendation to the Centre, asking it to revert to the pre-1953 status. Quoting sources close to interlocutors, the newspaper said the three-member team would propose an amendment in the Constitution to reverse whatever changes have taken place in the post-1953 decades. However, the interlocutors, who were appointed late last year to initiate dialogue with people of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh, have denied planning any such recommendation. However, any such move could be ill-advised. The presumption excludes the fact much of the alienation could be due to the dissatisfaction with the chief ministership of Farooq Abdullah after 1982, bureaucratic indifference and poor governance. It also ignores that the post-1989 spurt in insurgency could be due to the largely discredited elections of 1987, which many believe was rigged to favour the National Conference-Congress alliance. It does not take into account the heightened support from Pakistan’s agencies for militant and other activities aimed at fomenting instability. But the more important question here is whether the efforts at resolving the J&K issue should focus more on the ideas of integration – aspects which bring the state closer to the rest of India – or keep dwelling on separation – elements that ensure that the gap between both remains how it is. In the 58 years since Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest, the world has changed a lot. There are more factors around to bind the Kashmiris to India than earlier, interaction at different levels has gone up. The `recommendation’ would entail reversing these: the presidential promulgation of 1954, extending all provisions of the Constitution to the state; status of J&K as one of the constituent states of India; and officers of the all-India services. The result could be further isolation of the state from the national mainstream and gradual de-linking of contact at the administrative level. It is dangerous, both for the state and the country. Former governor of J&K, Jagmohan, said, “After 1953, various sections of governance were integrated with Jammu and Kashmir. If the state is provided with autonomy of the pre-1953 status, who will fund the government, how will people get their salaries and who will audit the accounts.” He added that the demand for autonomy was the charter of the state’s disintegration from India. Moreover, all the powers – legislative, executive and judicial – would be conferred on the council of ministers depriving the Kashmiris of political rights. The idea of devolution of powers is alright but autonomy is dangerous. The recommendation also overlooks the possibility of economic integration of the state with India and the opportunities for the Kashmiris there of.

[/caption] Such move could be ill-advised. The presumption excludes the fact that much of the alienation could be due to the dissatisfaction with the chief ministership of Farooq Abdullah after 1982, bureaucratic indifference and poor governance. It also ignores that the post-1989 spurt in insurgency could be due to the largely discredited elections of 1987, which many believe was rigged to favour the National Conference-Congress alliance. It does not take into account the heightened support from Pakistan’s agencies for militant and other activities aimed at fomenting instability. But the more important question here is whether the efforts at resolving the J&K issue should focus more on the ideas of integration – aspects which bring the state closer to the rest of India– or keep dwelling on separation – elements that ensure that the gap between both remains how it is. In the 58 years since Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest, the world has changed a lot. There are more factors around to bind the Kashmiris to India than earlier, interaction at different levels has gone up. The `recommendation’ would entail reversing these: the presidential promulgation of 1954, extending all provisions of the Constitution to the state; status of J&K as one of the constituent states of India; and officers of the all-India services. The result could be further isolation of the state from the national mainstream and gradual de-linking of contact at the administrative level. It is dangerous, both for the state and the country. Continues on the next page Former governor of J&K, Jagmohan, said, “After 1953, various sections of governance were integrated with Jammu and Kashmir. If the state is provided with autonomy of the pre-1953 status, who will fund the government, how will people get their salaries and who will audit the accounts.” He added that the demand for autonomy was the charter of the state’s disintegration from India. Moreover, all the powers –legislative, executive and judicial–would be conferred on the council of ministers depriving the Kashmiris of political rights. The idea of devolution of powers is alright but autonomy is dangerous. The recommendation also overlooks the possibility of economic integration of the state with India and the opportunities for the Kashmiris there of. On Jammu and Kashmir, we seem to be barking up the wrong tree again. The presumption that the developments post August 1953 left an indelible mark on the collective consciousness of a troubled state and set the stage for the progressive alienation of Kashmiris from India, is too sweeping in the first place. And then going back 58 years back in time to rearrange the pieces to fix the Kashmir problem looks impractical. Sheikh Abdullah, the popular National Conference leader and friend-turned-foe of then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was arrested and put in prison for 11 years on August 9, 1953 – with a small interval in 1958 – in the Kashmir Conspiracy Case. In a series of constitutional amendments and executive orders after that the Centre curtailed the state’s autonomy and expanded the sphere of its authority over J&K. The major political parties of the state – the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) – have been intermittently insisting on reverting to the pre-1953 status as a major step towards resolving the Kashmir imbroglio. Prior to 1953, the J&K government had exclusive jurisdiction over all departments, barring defence, foreign affairs and communications. An agreement signed between the state government and New Delhi in 1952 had provided other safeguards ensuring the special autonomous status for the state within the Indian Union. The BJP and the Congress, the major parties in the country, are opposed to the idea. Both are unwilling, though in different degrees, to let the state have more autonomy than what it already has. The debate is back again. According to a report in The Hindustan Times, the Central interlocutors on J&K are contemplating making a recommendation to the Centre, asking it to revert to the pre-1953 status. Quoting sources close to interlocutors, the newspaper said the three-member team would propose an amendment in the Constitution to reverse whatever changes have taken place in the post-1953 decades. However, the interlocutors, who were appointed late last year to initiate dialogue with people of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh, have denied planning any such recommendation. However, any such move could be ill-advised. The presumption excludes the fact much of the alienation could be due to the dissatisfaction with the chief ministership of Farooq Abdullah after 1982, bureaucratic indifference and poor governance. It also ignores that the post-1989 spurt in insurgency could be due to the largely discredited elections of 1987, which many believe was rigged to favour the National Conference-Congress alliance. It does not take into account the heightened support from Pakistan’s agencies for militant and other activities aimed at fomenting instability. But the more important question here is whether the efforts at resolving the J&K issue should focus more on the ideas of integration – aspects which bring the state closer to the rest of India – or keep dwelling on separation – elements that ensure that the gap between both remains how it is. In the 58 years since Sheikh Abdullah’s arrest, the world has changed a lot. There are more factors around to bind the Kashmiris to India than earlier, interaction at different levels has gone up. The `recommendation’ would entail reversing these: the presidential promulgation of 1954, extending all provisions of the Constitution to the state; status of J&K as one of the constituent states of India; and officers of the all-India services. The result could be further isolation of the state from the national mainstream and gradual de-linking of contact at the administrative level. It is dangerous, both for the state and the country. Former governor of J&K, Jagmohan, said, “After 1953, various sections of governance were integrated with Jammu and Kashmir. If the state is provided with autonomy of the pre-1953 status, who will fund the government, how will people get their salaries and who will audit the accounts.” He added that the demand for autonomy was the charter of the state’s disintegration from India. Moreover, all the powers – legislative, executive and judicial – would be conferred on the council of ministers depriving the Kashmiris of political rights. The idea of devolution of powers is alright but autonomy is dangerous. The recommendation also overlooks the possibility of economic integration of the state with India and the opportunities for the Kashmiris there of.

J&K: Rearranging pre-1953 pieces won’t take us far

Akshaya Mishra

• February 3, 2022, 13:54:46 IST

The idea of taking the equations back by more than 58 years will not be beneficial for Kashmiris. It will create more problems for the Indian state too.

Advertisement

)

End of Article