Barely minutes after the press conference on Wednesday by Arvind Kejriwal and his band of anti-corruption activists, at which they ’exposed’ BJP president Nitin Gadkari’s ‘business empire’, BJP leaders, who were bracing for rather more bad news, were visibly relieved. And their relief found expression in an eruption of sporting metaphors calculated to convey that Gadkari had, in their estimation, niftily dodged a bullet. Kejriwal had

scored a self-goal

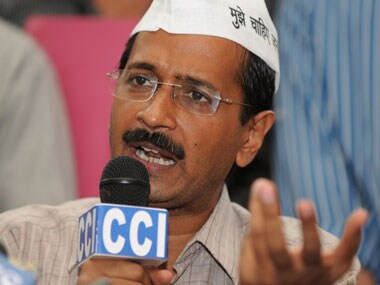

, said BJP leader Arun Jaitley. No, no, Kejriwal was out hit-wicket, said party spokesperson Ravi Shankar Prasad. BJP leaders were evidently taking heart from the fact that there was not much that was new or explosive in the charges that Kejriwal and his team had levelled against Gadkari. If anything, they claimed, Kejriwal’s expose had broadcast to the wider world the good work that Gadkari was doing as a “social entrepreneur” in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. Gadkari’s trust may have secured 100 acres of land on lease from the Maharashtra Government, with former Irrigation Minister Ajit Pawar overruling strenuous objections from the Irrigation Secretary and moving with extraordinary agility to facilitate it - in the same way that the Haryana government moved in the case of Sonia Gandhi’s son-in-law Robert Vadra’s land dealings in Haryana. But then, BJP leaders argue, since Gadkari’s trust was offering subsidised sugarcane saplings for farmers, and since Gadkari himself did not personally profit from the land transaction or the social entrepreneurship project, it was all good. [caption id=“attachment_492729” align=“alignright” width=“380”]

Arvind Kejriwal is sowing the wind, and is whipping up a whirlwind. AFP[/caption] On just the legal facts of the case, there may be some merit in the BJP’s claim. In Vadra’s case, his private businesses made windfall profits on a Rs 7.5 crore investment in a plot of land in Haryana (which purchase itself was funded by DLF), whose value shot up to Rs 58 crore in just months because Haryana bureaucrats moved in myriad ways their miracles to perform. Given that Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi (where Vadra’s land transactions occurred) were all Congress-ruled States and given the enormous clout that Vadra notionally enjoyed as Sonia Gandhi’s son-in-law, the case for possible influence peddling for private gain has been well-established. In contrast, Maharashtra is a Congress-NCP-ruled State where the BJP is in Opposition. In any case, Gadkari’s trust didn’t acquire the land - it merely took it on lease - and it at least has the fig leaf of being a “social entrepreneurship” venture from which Gadkari derived no personal benefit. To that extent, it appears that Kejriwal’s expose of Gadkari was a bit of a damp squib. His attempt to project himself as an “equal-opportunity” whistleblower against alleged corruption - by establishing a ‘corruption’ equivalence between the Congress or the BJP - may appear to have gotten off to a less-than-spectacular start. But such an assessment overlooks the larger message emerging from Kejriwal’s ’expose’ of Gadkari, and indeed from what Kejriwal has succeeded in doing with his recent burst of political activism targeting Vadra, Law Minister Salman Khurshid, and now Gadkari. At the very least, Kejriwal and his team made out an eloquent case to establish that established rules were overruled to lease out land (that had been acquired from farmers for a dam project) to Gadkari’s trust. However noble the trust’s operations, that irregularity - and the swift manner in which the Ajit Pawar moved to regularise the transaction - points to the extraordinary political goodwill that Gadkari enjoyed with Pawar. If you can bend the arc of governmental rules to your advantage, even when you are in Opposition, you have it made. Secondly, Kejriwal and Prashant Bhushan connected the dots well enough to make the point that the symbiotic nature of such relationships between parties and individuals across the political spectrum shows up the political ecosystem as a cosy club where members do each other a good turn - and in turn are rewarded when today’s opposition becomes tomorrow’s ruling party. It is the nature of such a relationship that accounts for the BJP’s reluctance to target Vadra, even though they knew there was much mischief afoot; likewise, as Congress spokesperson Digvijay Singh claimed the other day, the Congress too abided by the ‘protocol’ of not making an issue of former Prime Minister AB Vajyapee’s foster son-in-law Ranjan Bhattacharya’s business transactions, shadowy though they too appeared to be. (In fact, the Congress did invoke Bhattacharya’s name, but not with any particular vigour.) To the extent that Kejriwal and his team were able to establish that the BJP - and, in particular, Gadkari - have made transactional compromises that weaken their resolve in targeting corruption by the Congress, Kejriwal’s larger plan has succeeded. It is also difficult to overlook the effect that Kejriwal and his high-decibel campaign are having in the political and administrative ecosystem. Kejriwal is,

as we have noted earlier

, looking to stir things up in the system. It may seem like muckraking or hit-and-run tactics, but even in cases where he started off without adequate evidence of illegality (for instance, in the Vadra case), subsequent events have validated and taken forward his allegations. Illustratively, in Vadra’s case, the mere fact that he brought the issue back in the public domain has prompted a scrutiny of Vadra’s business dealings, which in turn have shown up the inconsistencies in his firms’ balance sheets and the accounts of DLF and Corporation Bank, to name just two entities. Indicatively, Vadra’s books claim that he secured an overdraft of Rs 9 crore from Corporation Bank; the bank claims that no such facility was extended. The question then arises: from where did Vadra secure the money, which funded his land purchases? And why isn’t an investigation ordered into what then amounts to a falsehood in Vadra’s company’s official filings. Also, as the extraordinary action of Haryana IAS officer Ashok Khemka (

details here

) shows, Kejriwal’s high-profile campaign is emboldening whistleblowers within the administrative system too to stand up and be counted. As a result, the mutation order on one of Vadra’s land transactions has been cancelled, and an investigation has been ordered into the dealings. That would never have happened if Kejriwal hadn’t spoken up about Vadra in the way that he did. Likewise in Salman Khurshid’s case, merely by raising the political pitch, Kejriwal has caused Khurshid to implode politically. More and more muck about the forgeries and falsifications that are even today being resorted to by Khurshid’s trust is tumbling out. And now, the Law Minister has been caught on candid camera issuing what amounts to an open death threat to Kejriwal. Who would have believed, barely a few days ago, that an “Oxford-educated” Minister - and a politician so suave as Khurshid - would issue open threats like these? What Kejriwal is doing with his shrill campaign is to put our political leaders in a pressure cooker situation. Things happen along the way, and as happened with Vadra and Khurshid, more scandalous exposures build on the initial weak accusations. And as Vadra did (with his remark about

“mango people in a banana republic”

) and Khurshid did (with his threat to Kejriwal), those who can’t handle the pressure implode on their own accord. Likewise, in Gadkari’s case too, Kejriwal’s allegations may seem tame today, and BJP leaders may be breathing easy. But already, the momentum is building up with Ram Jethmalani promising to ferret out yet more damaging evidence on Gadkari. The last word hasn’t been said on the subject, and it’s too early to say, based on just Wednesday’s disclosures, that Kejriwal has either scored a self-goal or is out hit-wicket. Kejriwal is going about sowing the wind. But his actions are having a catalytic effect - and are whipping up a whirlwind. And in all that dust that is whipped up, the masks are falling off even established political leaders and parties.

Arvind Kejriwal is sowing the wind, and is whipping up a whirlwind. AFP[/caption] On just the legal facts of the case, there may be some merit in the BJP’s claim. In Vadra’s case, his private businesses made windfall profits on a Rs 7.5 crore investment in a plot of land in Haryana (which purchase itself was funded by DLF), whose value shot up to Rs 58 crore in just months because Haryana bureaucrats moved in myriad ways their miracles to perform. Given that Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi (where Vadra’s land transactions occurred) were all Congress-ruled States and given the enormous clout that Vadra notionally enjoyed as Sonia Gandhi’s son-in-law, the case for possible influence peddling for private gain has been well-established. In contrast, Maharashtra is a Congress-NCP-ruled State where the BJP is in Opposition. In any case, Gadkari’s trust didn’t acquire the land - it merely took it on lease - and it at least has the fig leaf of being a “social entrepreneurship” venture from which Gadkari derived no personal benefit. To that extent, it appears that Kejriwal’s expose of Gadkari was a bit of a damp squib. His attempt to project himself as an “equal-opportunity” whistleblower against alleged corruption - by establishing a ‘corruption’ equivalence between the Congress or the BJP - may appear to have gotten off to a less-than-spectacular start. But such an assessment overlooks the larger message emerging from Kejriwal’s ’expose’ of Gadkari, and indeed from what Kejriwal has succeeded in doing with his recent burst of political activism targeting Vadra, Law Minister Salman Khurshid, and now Gadkari. At the very least, Kejriwal and his team made out an eloquent case to establish that established rules were overruled to lease out land (that had been acquired from farmers for a dam project) to Gadkari’s trust. However noble the trust’s operations, that irregularity - and the swift manner in which the Ajit Pawar moved to regularise the transaction - points to the extraordinary political goodwill that Gadkari enjoyed with Pawar. If you can bend the arc of governmental rules to your advantage, even when you are in Opposition, you have it made. Secondly, Kejriwal and Prashant Bhushan connected the dots well enough to make the point that the symbiotic nature of such relationships between parties and individuals across the political spectrum shows up the political ecosystem as a cosy club where members do each other a good turn - and in turn are rewarded when today’s opposition becomes tomorrow’s ruling party. It is the nature of such a relationship that accounts for the BJP’s reluctance to target Vadra, even though they knew there was much mischief afoot; likewise, as Congress spokesperson Digvijay Singh claimed the other day, the Congress too abided by the ‘protocol’ of not making an issue of former Prime Minister AB Vajyapee’s foster son-in-law Ranjan Bhattacharya’s business transactions, shadowy though they too appeared to be. (In fact, the Congress did invoke Bhattacharya’s name, but not with any particular vigour.) To the extent that Kejriwal and his team were able to establish that the BJP - and, in particular, Gadkari - have made transactional compromises that weaken their resolve in targeting corruption by the Congress, Kejriwal’s larger plan has succeeded. It is also difficult to overlook the effect that Kejriwal and his high-decibel campaign are having in the political and administrative ecosystem. Kejriwal is,

as we have noted earlier

, looking to stir things up in the system. It may seem like muckraking or hit-and-run tactics, but even in cases where he started off without adequate evidence of illegality (for instance, in the Vadra case), subsequent events have validated and taken forward his allegations. Illustratively, in Vadra’s case, the mere fact that he brought the issue back in the public domain has prompted a scrutiny of Vadra’s business dealings, which in turn have shown up the inconsistencies in his firms’ balance sheets and the accounts of DLF and Corporation Bank, to name just two entities. Indicatively, Vadra’s books claim that he secured an overdraft of Rs 9 crore from Corporation Bank; the bank claims that no such facility was extended. The question then arises: from where did Vadra secure the money, which funded his land purchases? And why isn’t an investigation ordered into what then amounts to a falsehood in Vadra’s company’s official filings. Also, as the extraordinary action of Haryana IAS officer Ashok Khemka (

details here

) shows, Kejriwal’s high-profile campaign is emboldening whistleblowers within the administrative system too to stand up and be counted. As a result, the mutation order on one of Vadra’s land transactions has been cancelled, and an investigation has been ordered into the dealings. That would never have happened if Kejriwal hadn’t spoken up about Vadra in the way that he did. Likewise in Salman Khurshid’s case, merely by raising the political pitch, Kejriwal has caused Khurshid to implode politically. More and more muck about the forgeries and falsifications that are even today being resorted to by Khurshid’s trust is tumbling out. And now, the Law Minister has been caught on candid camera issuing what amounts to an open death threat to Kejriwal. Who would have believed, barely a few days ago, that an “Oxford-educated” Minister - and a politician so suave as Khurshid - would issue open threats like these? What Kejriwal is doing with his shrill campaign is to put our political leaders in a pressure cooker situation. Things happen along the way, and as happened with Vadra and Khurshid, more scandalous exposures build on the initial weak accusations. And as Vadra did (with his remark about

“mango people in a banana republic”

) and Khurshid did (with his threat to Kejriwal), those who can’t handle the pressure implode on their own accord. Likewise, in Gadkari’s case too, Kejriwal’s allegations may seem tame today, and BJP leaders may be breathing easy. But already, the momentum is building up with Ram Jethmalani promising to ferret out yet more damaging evidence on Gadkari. The last word hasn’t been said on the subject, and it’s too early to say, based on just Wednesday’s disclosures, that Kejriwal has either scored a self-goal or is out hit-wicket. Kejriwal is going about sowing the wind. But his actions are having a catalytic effect - and are whipping up a whirlwind. And in all that dust that is whipped up, the masks are falling off even established political leaders and parties.

Venky Vembu attained his first Fifteen Minutes of Fame in 1984, on the threshold of his career, when paparazzi pictures of him with Maneka Gandhi were splashed in the world media under the mischievous tag ‘International Affairs’. But that’s a story he’s saving up for his memoirs… Over 25 years, Venky worked in The Indian Express, Frontline newsmagazine, Outlook Money and DNA, before joining FirstPost ahead of its launch. Additionally, he has been published, at various times, in, among other publications, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, Outlook, and Outlook Traveller.

)