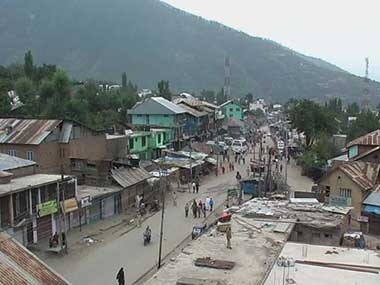

Kishtwar: In the middle of Kishtwar’s central market, two shopkeepers stand witness to the communal polarization in a town that was once an example of communal harmony in the Chenab valley. Since August 9, Subash Kashap, 42, and Noor Mohammad, 48, both with their shops facing each other, have not had their friendly morning chatter, a routine of 20 years. The events of the fateful day ended their friendship of more than two decades, just as it did the hundreds of years of communal harmony in the town. Kishtwar is 226 kilometres from Jammu, the winter capital of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The conscious politico-religious assimilation of Jammu has never crossed into Kishtwar town, which has Hindu and Muslim in a 50:50 ratio. Until now. “On that day, my neighbors told me he was among the crowd who torched my shop. My entire shop was burnt down,” Kashap says, referring to his long time friend Mohammad. Mohammad repeated similar charges against his friend. Early one December morning, as sunbeams kissed the tin roofs of the Kishtwar town, the house of famous Gujari poet Ghulam Nabi is quiet. Nabi is 68, and has observed the politics of Chenab valley for decades. In hushed tones, he points to the first floor that caught fire during the riots which spread like wildfire from the neighboring shops. “I don’t regret this,” he says, pointing to the first storey of his house that was burnt down. “But what we have almost lost is the culture of coexistence, which was more important than any houses and building. It should not have happened for the second time.” [caption id=“attachment_128392” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  A market in Kishtwar that was burned down. Shahid Tantray / Firstpost[/caption] Politics of hatred, he says, not only divided people but created identity consciousness which may have worse consequences in the future. It can slice a home into two, turn friends into foes. On August 9, hundreds of people marched through the Kuleed Chowk to join an Eid congregation of over 20,000 people at Chowgan ground. A policemen assigned to a local BJP leader was driving from the other side when his motorcycle crashed into some Muslims who in turn slapped him. Later, the policemen allegedly ganged up with some of his friends and began pelting stones at the procession of Muslims who were going to attend Eid prayers, according to eyewitnesses. Within minutes, groups of young Muslim men were attacking Hindu-owned properties and young Hindu men vented their anger on Muslim-owned properties, following which the two main markets were reduced to cinders in minutes. Smoke was still billowing from the markets when the Army marched into the town to put an end to the senseless violence that left three people dead and more then 30 injured. According to locals, migrant labourers living on the edge of town smelled an opportunity and looted shops of both communities, sometimes aligning with Hindus and sometimes with Muslims. The district administration assessed the cost of property loss at Rs 13.86 crore. Most of the violence and thieving by two communities happened in one day. In the aftermath of the violence, local politicians sensed an opportunity and accused the sitting MLA and the then J&K’s minister of state for home, Sajjad Kitchloo, of playing a hand in the riots. Pressure built on him, forcing him to resign. [caption id=“attachment_128393” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Central market in Kishtwar. Shahid Tantray / Firstpost[/caption] For the first time in the history of Jammu and Kashmir, a minister’s resignation was forced by the demand of the opposition party. With an eye on the coming elections, both BJP and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) sent their delegations to the town to ‘comfort’ people. Ishtiyaq Ahmad Waza, a short, lean man in his early forties, is an influential businessmen and a local PDP leader. He is confident that PDP will win the seat in the upcoming assembly elections. Apart from the anti-incumbency factor against Kitchloo, the sitting MLA, his failure to stop the riots are fresh in the minds of the people. “He was not just a local MLA but also a minster. Entire administration was at his disposal but he failed to stop the riots. Kishtwar has never been a communally sensitive place but in the last decade, religious parties have been trying to create communal tensions in the town which is not good for any society. We have to learn how to live together with tolerance and brotherhood,” Waza told Firstpost. A look at the contemporary history of the town reveals that barring 2008, during the Amarnath agitation when four people were killed in August that year, the town has never seen communal riot. Both communities have lived in co-existence since centuries and even visited each other’s religious places. While the present coalition partners in the state - National Conference and Congress - have dominated the political maneuvering in the region, the NC’s MLA Sajjad Kitchloo has won the seat two times. Before him, his father Bashir Ahmad Kichloo managed to keep the seat four times. When militancy erupted in Kashmir valley, the BJP made it a local election issue and managed to rise from 1,066 votes in 1983 to 10,900 votes in 1996. But that was not enough to win a seat. The junior Kitchloo polled 17,889 votes, winning the seat for the first time after his father. In the Assembly elections of 2008, BJP’s Sunil Kumar took 16,783 votes and was rather close to Kitchloo who polled 19,248 votes. Rakesh Gupta, a trade union leader in Kishtwar, says the BJP and PDP would be fighting each other neck and neck and that the NC and Congress are nowhere in the picture this time around when the state goes to polls in s014. Kishtwar is a divided house now, more than before. The fault lines between the two groups have only congealed after the events of August 9. The town is divided on every other issue; be it development or politics. The Muslims, for the first time, have decided to vote for a Kashmir centric party, while Hindus have taken a vow to side with the BJP, say locals. When the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi held his Lalkar rally in Jammu, when more than seven thousand BJP supporters travelled from Kishtwar town to Jammu to attend the rally, it was amply clear that the town stands tragically polarised. “But I am sure if the mood among the voters remains as it is today, BJP will for sure take the seat for the first time in Chenab valley,” Gupta says. A senior police official based in Kishtwar, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said it would be naive to say that there is no visible tension in the area. “It has sustained and it probably would up to the Assembly elections. We are always prepared to deal with any kind of situation. Since August 9, as accused were arrested from both communities, there is a visible resentment against the police too, from both communities. Both feel that the police is siding with one or the other.” Anil Dasgotra, who was arrested following the riots said his neighbors and he never mixed after that, not even for a single day after the riots. “My brother got married recently and we didn’t invite them. Earlier the weeding would have been impossible without their participation," Dasgotra says of his Muslim neighbours. The Kashmir Centre for Social and Development Studies (KCSDS), a rights activists’ group, after releasing their report early this August said an immediate ban on the “jingoistic communal parties” was necessary for lasting peace in the area. The group said, “We believe that the parties like BJP, Shiv Sena, VHP and Bajrang Dal have no place in J&K where people of all faiths have been living in harmony for centuries. No politician of these parties should be allowed to enter the state to fulfil his or her ulterior motives, the local politicians of these parties need to be booked for their nefarious activities and direct involvement in the Kishtwar incidents.” However Separatist leader Syed Ali Geelani blames Village Defence Committees (VDCs) for the trouble in the town. “Until and unless the VDCs are disarmed and dissolved, threat will haunt and prevail in Chenab Valley and Muslim Community will feel insecure," he said. If the BJP or PDP manages to win Kishtwar seat, it would be a straightforwrad path to confrontationist politics in future. That is what Nabi the poet doesn’t favor. “It would mean the victory of divisive forces,” Nabi says.

The Kishtwar seat is being eyed by the PDP and the BJP, its NC MLA forced to resign as minister. That would mean confrontationist politics returns to Jammu and Kashmir.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)