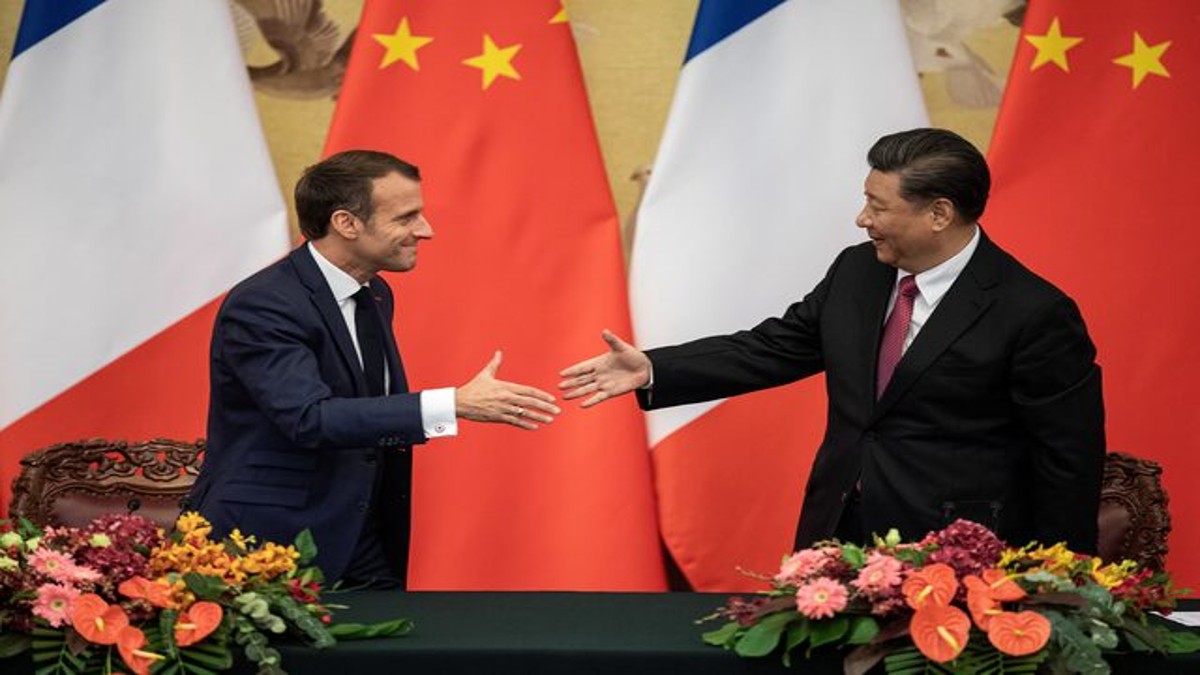

On his first visit to Europe post-pandemic, Xi Jinping met French President Emmanuel Macron. Xi lauded China’s ties with France as a “model for the international community amid threats of a trade war over Chinese electric cars and French cognac". Xi Jinping’s tour through Europe, analysts point out, highlighted China’s audacious strategy to exploit the fissures within Europe amid great power contestation.

Among many other developments, the armed forces of China and France announced the setting up of a new inter-theatre cooperation and dialogue mechanism. This collaboration between the two militaries’ naval and air forces is aimed at further deepening mutual trust and cooperation and jointly safeguarding regional security and stability.

Such a move towards forging closer Sino-French military ties, especially amid Beijing’s assertive manoeuvres in the Indo-Pacific and the South China Sea, begs the question: Can Europe, and particularly France, remain a reliable ally, or will it become more accommodating of China’s controversial actions in its neighbourhood? Countries like India are watching closely, concerned about France and Europe in the future and potentially succumbing to China’s diplomatic and economic enticements.

China claims to be “not at the origin of the Russian-Ukraine crisis, nor a party to it, nor a participant", and thus legitimises its silence. Can we anticipate a similar approach by Europe on issues concerning Taiwan and the Philippines?

In the past few years, France’s relationship with China has been marked by a mixture of scepticism and strategic engagement, reflecting broader geopolitical objectives and national interests. In the recent past, France has been quite critical of China, viewing it as a ‘strategic threat’. The 2021 update to France’s 2017 Defence and National Security Strategic Review painted China as a ‘systemic rival’, ’economic competitor’, and ‘sometimes an important diplomatic partner’. Even as Paris sought engagement with Beijing in 2019, substantial tensions clearly existed. During Xi Jinping’s previous European tour, President Macron rallied a united European front to challenge Beijing on critical European issues like unfair trade practices, restricted market access for European companies, opaque financing under the BRI, and human rights abuses in Tibet and Xinjiang.

Recent events and official statements have further underscored this stance. A parliamentary report on foreign interference in France, requested by Marine Le Pen’s far-right party, highlighted China’s “aggressive and increasingly malicious methods”. Labelling China as the “second most serious threat to France after Russia”, the report echoed sentiments from Bernard Emié, Director of French External Intelligence (DGSE), who described China as an ‘aggressive power’ with ‘unbridled diplomacy’.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsFurthermore, the issue of France selling arms to Taiwan resurfaced during the pandemic when Taiwan announced plans to buy defence equipment from France to upgrade missile systems on French warships purchased in 1991 and 1992. Beijing expressed ‘serious concern’ and urged Paris to avoid actions that could strain Sino-French ties. Following Chinese air intrusions into Taiwan’s air defence zone, a French delegation led by former defence minister Alain Richard visited Taipei to meet with President Tsai Ing-wen. This visit was seen as a powerful symbol of France’s commitment to opposing China’s unilateral aggression and supporting peace, security, and stability in the Indo-Pacific.

Maintaining this assertive stance, France forged strategic partnerships with nations, sharing its concerns about China’s expanding influence. Recently, Macron and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida agreed to negotiate a reciprocal access agreement to facilitate visits and joint exercises between the Japan Self-Defence Forces and the French military. This pact aims to bolster military cooperation and readiness in the Indo-Pacific, where both nations seemed to be eager to counterbalance China’s growing footprint. Similarly, France strengthened its defence ties with India as well. Earlier this year, Paris and New Delhi agreed on the joint production of defence equipment, including helicopters and submarines, for the Indian armed forces and other friendly nations.

Nonetheless, in a paradoxical twist that raises eyebrows and questions France’s reliability, Paris also moved towards closer security cooperation with China. This unexpected manoeuvre, despite France’s alliances with nations wary of Beijing, highlights a complex and nuanced approach adopted by Paris. On Xi Jinping’s recent visit to Europe, France and China announced a ground-breaking inter-theatre cooperation and dialogue mechanism involving their naval and air forces. This initiative aims to deepen mutual trust and cooperation, in stark contrast to France’s vocal criticism of China’s aggressive tactics and human rights abuses.

This move underscores a strategic balancing act by Paris, but at the same time, it also casts doubt on its steadfastness as a partner to countries like India and Japan. While bolstering its defence ties with these nations to counterbalance China’s influence, France’s simultaneous engagement with Beijing could be seen as undermining its commitments towards safeguarding global norms and values.

France seems to have executed a dramatic 180-degree pivot, with recent conversations emerging such as, “Which forces are hyping the China threat and pushing to turn China into an enemy? China is a friend; it’s also an economic competitor.” This surprising shift militarily towards China, especially amid escalating geopolitical tensions, paints a picture of France striving to maintain diplomatic flexibility. However, this approach could also be seen as France hedging its bets, seeking to secure its interests on multiple fronts, all while risking the trust of its traditional allies.

These actions echo Macron’s frequent assertion that France is “allied but not aligned”, showcasing its commitment to the idea of multi-alignment. They also underscore just how divided Europe’s commitment and vision for the region are. Their cautious reminder to Asia—_“What happens in Europe has security implications in Asia”—_is in stark contrast with their attitude towards security perceptions in Asia. For this reason, Europe’s stake in the region remains more about economics than security. For countries like France, China isn’t a direct military threat, but for countries in the Indo-Pacific, the story is entirely different. If there is anything to deduce from Paris’ recently growing military cooperation with Beijing, it is that Asian powers need to fend for themselves; they cannot rely entirely on Europe.

The author is a researcher at the East Asia Centre, MP-IDSA, New Delhi, India. The views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Firstpost’s views.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)